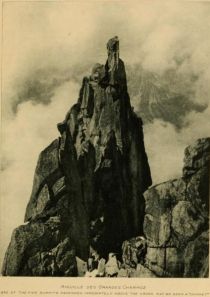

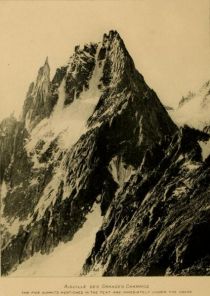

Aiguille des Grandes Charmoz

There are no peaks in the world affording better rock climbing than some of the „aiguilles“ about Chamonix, and few afford as good. Among such aiguilles may be mentioned the two points of the Dru, the Grépon, the Requin and the Grandes Charmoz. Their rocks are firm and offer passages about as difficult as it is possible for human beings to ascend or descend without artificial aid; indeed, to the uninitiated some of the places which with care and effort may nevertheless be scaled must often seem quite inaccessible. The joy and satisfaction of such climbing are very great, and those who have once indulged in it almost invariably return to it. Peaks of the character mentioned can be climbed only under favorable conditions. Above all, the rocks must be free from snow, for its presence not only makes them slippery but renders it difficult or impossible to find, or when found to use, the hand and foot-holds.

The Grandes Charmoz are one of the several splendid aiguilles with numerous sharp and jagged summits which form the westerly boundary of the Mer de Glace. With a view to its ascent we slept at Montanvert (already referred to) the day after climbing Mont Blanc, leaving it at about 2 a. m. on the following day, Friday, August 29. We proceeded for three and a half hours without halt, except to adjust the rope upon reaching the ice, and were then at the point known as the „Rognon,“ well up on the Glacier de Nantillon, where we breakfasted. The weather could not have been better, and from the Rognon we walked rapidly up and across the snow above this glacier, until we were at the foot of the long couloir which leads to the depression between the Charmoz and the Grépon. There our knapsacks were deposited, as well as two of the three ice-axes, for some very hard rock work lay before us and we wished to be burdened with nothing that was not indispensable. We placed a small amount of food in our pockets. After ascending the couloir for three-quarters of an hour we turned sharply to the left (the Grépon lying to the right) and were soon thereafter at close quarters with rocks which afforded us splendid climbing for about an hour. At one point we found ourselves face to face with an exceedingly steep and narrow gully, or chimney, about twenty feet high, which it was necessary to ascend by the sides, where the holds were few and awkwardly situated. A part of the distance there was a small crack. In the course of this bit of climbing one has to grip with the knees surfaces at a wide angle and, rising, throw oneself quickly and adroitly to the right and there secure a new hold higher up. The effort involved in surmounting such an obstacle as this chimney is very great and almost certain to leave one blown and ready to pause for a moment. The highest summit, called the Grande Pointe, was reached first, and we found the top of it to be a very small spot, with precipices in several directions. But the rocks were secure, and we remained several minutes to enjoy the beautiful view and other interesting features of the scene about us.

The rope had been playing an important part in our climbing, as it does in every ascent of any magnitude, whether on snow or on rocks, and a word here as to its proper function will not be out of place. Its use on snow is readily explained. With three on the rope, if one of the party break through the surface, the others can prevent him from disappearing very far. Whereas any one, however careful, may break through the snow, the good climber will rarely, if ever, slip on rocks which he has once determined are fit to be climbed. And yet even in the case of such climbers the presence of the rope is indispensable as a means of steadying them and furnishing them with the moral courage or support necessary to enable them to attack difficult places. The question may be asked whether in the unlikely event of a slip the rope can be made to guard against its consequences. The answer is that usually it can, provided it be used with intelligence and skill; for at difficult places only one member of the party will advance at a time, and before he advances at least one of the others will lodge himself in a secure position and, if possible, double the rope around a firm knob of rock.

In connection with what is said here it must be remembered that only expert climbers can with safety undertake to scale rocks which present difficulties of the first order, and each member of the party should have full confidence in the ability of each of the others not only to climb without slipping, but also to render some assistance if the unexpected slip actually happen; and when the party is so constituted serious accident is a matter of very rare occurrence. He who finds himself requiring much active assistance from the rope on rocks should remain below, for it is not the province of the rope to enable the incompetent to be dragged up peaks. But there are instances where assistance is as proper as it is necessary, as when an almost perpendicular wall is met, with no cracks or holds and considerably higher than the reach of the leader. He may be able to ascend it only by first placing himself on the shoulders of the second man and so on. Obviously in such a case the last man must haul himself up by the rope, or be hauled up by it.

The really serious work of the day came after leaving the Grande Pointe, for we had set ourselves the task of traversing, or crossing, the five principal summits of the Charmoz. The next one is known as Bâton Wils. Before reaching it we had to pass an extremely narrow shelf with a long drop (where anything resembling dizziness would have been entirely out of place) and scale another difficult chimney. Boulders and stones at great heights in the Alps are usually found placed upon each other in a manner most extraordinary and perplexing to the climber; why there should be fewer hand and foot-holds at these lofty elevations than lower down, I do not know. At a later point of the climb we came to two rocks, one known as the Pas Carré, which could not be crossed and had to be turned by their steep, rectangular corners to the left. Neither of these corners was inviting, for there was no place to put the feet except where the rocks curved slightly outwards near their base (and even then one could grip only with the tips of the boots), while the depths below were considerable. Before it was deemed safe to pass either, the second rope was so adjusted around firm knobs of rock as to serve as what the guides termed a „rampe“ (literally, hand rail) in the event of a slip, of which, however, no one was guilty.

Thus, for about two hours we enjoyed what may be fairly termed severe climbing between five of the summits of this interesting aiguille. Fortunately the weather continued fine. It was warm and clear and there was not a breath of wind. We left the mountain by way of the fifth peak, from which we descended directly, encountering in the course of this descent a number of bad gullies with steep, smooth sides. Down three of them it was impossible to go except with the use of the second rope, which in each instance was carefully adjusted around a knob of rock at the top, so that it could be withdrawn by the last man. We regained the snow at the point where we had left the knapsacks and ice-axes, and once on it realized that we would have to make haste, for it was very warm and some three hundred feet of the route were likely at any moment to be swept by avalanches from the steep glacier which came down from the Aiguille de la Blaitiere. Across this space we hurried in double quick step and without further incident reached the Rognon at 1.30 and Montanvert at 4. The climb proved to be one of the best and most exciting I have ever enjoyed and also the last one of this my fifteenth season in the Alps.

The Grandes Charmoz are one of the several splendid aiguilles with numerous sharp and jagged summits which form the westerly boundary of the Mer de Glace. With a view to its ascent we slept at Montanvert (already referred to) the day after climbing Mont Blanc, leaving it at about 2 a. m. on the following day, Friday, August 29. We proceeded for three and a half hours without halt, except to adjust the rope upon reaching the ice, and were then at the point known as the „Rognon,“ well up on the Glacier de Nantillon, where we breakfasted. The weather could not have been better, and from the Rognon we walked rapidly up and across the snow above this glacier, until we were at the foot of the long couloir which leads to the depression between the Charmoz and the Grépon. There our knapsacks were deposited, as well as two of the three ice-axes, for some very hard rock work lay before us and we wished to be burdened with nothing that was not indispensable. We placed a small amount of food in our pockets. After ascending the couloir for three-quarters of an hour we turned sharply to the left (the Grépon lying to the right) and were soon thereafter at close quarters with rocks which afforded us splendid climbing for about an hour. At one point we found ourselves face to face with an exceedingly steep and narrow gully, or chimney, about twenty feet high, which it was necessary to ascend by the sides, where the holds were few and awkwardly situated. A part of the distance there was a small crack. In the course of this bit of climbing one has to grip with the knees surfaces at a wide angle and, rising, throw oneself quickly and adroitly to the right and there secure a new hold higher up. The effort involved in surmounting such an obstacle as this chimney is very great and almost certain to leave one blown and ready to pause for a moment. The highest summit, called the Grande Pointe, was reached first, and we found the top of it to be a very small spot, with precipices in several directions. But the rocks were secure, and we remained several minutes to enjoy the beautiful view and other interesting features of the scene about us.

The rope had been playing an important part in our climbing, as it does in every ascent of any magnitude, whether on snow or on rocks, and a word here as to its proper function will not be out of place. Its use on snow is readily explained. With three on the rope, if one of the party break through the surface, the others can prevent him from disappearing very far. Whereas any one, however careful, may break through the snow, the good climber will rarely, if ever, slip on rocks which he has once determined are fit to be climbed. And yet even in the case of such climbers the presence of the rope is indispensable as a means of steadying them and furnishing them with the moral courage or support necessary to enable them to attack difficult places. The question may be asked whether in the unlikely event of a slip the rope can be made to guard against its consequences. The answer is that usually it can, provided it be used with intelligence and skill; for at difficult places only one member of the party will advance at a time, and before he advances at least one of the others will lodge himself in a secure position and, if possible, double the rope around a firm knob of rock.

In connection with what is said here it must be remembered that only expert climbers can with safety undertake to scale rocks which present difficulties of the first order, and each member of the party should have full confidence in the ability of each of the others not only to climb without slipping, but also to render some assistance if the unexpected slip actually happen; and when the party is so constituted serious accident is a matter of very rare occurrence. He who finds himself requiring much active assistance from the rope on rocks should remain below, for it is not the province of the rope to enable the incompetent to be dragged up peaks. But there are instances where assistance is as proper as it is necessary, as when an almost perpendicular wall is met, with no cracks or holds and considerably higher than the reach of the leader. He may be able to ascend it only by first placing himself on the shoulders of the second man and so on. Obviously in such a case the last man must haul himself up by the rope, or be hauled up by it.

The really serious work of the day came after leaving the Grande Pointe, for we had set ourselves the task of traversing, or crossing, the five principal summits of the Charmoz. The next one is known as Bâton Wils. Before reaching it we had to pass an extremely narrow shelf with a long drop (where anything resembling dizziness would have been entirely out of place) and scale another difficult chimney. Boulders and stones at great heights in the Alps are usually found placed upon each other in a manner most extraordinary and perplexing to the climber; why there should be fewer hand and foot-holds at these lofty elevations than lower down, I do not know. At a later point of the climb we came to two rocks, one known as the Pas Carré, which could not be crossed and had to be turned by their steep, rectangular corners to the left. Neither of these corners was inviting, for there was no place to put the feet except where the rocks curved slightly outwards near their base (and even then one could grip only with the tips of the boots), while the depths below were considerable. Before it was deemed safe to pass either, the second rope was so adjusted around firm knobs of rock as to serve as what the guides termed a „rampe“ (literally, hand rail) in the event of a slip, of which, however, no one was guilty.

Thus, for about two hours we enjoyed what may be fairly termed severe climbing between five of the summits of this interesting aiguille. Fortunately the weather continued fine. It was warm and clear and there was not a breath of wind. We left the mountain by way of the fifth peak, from which we descended directly, encountering in the course of this descent a number of bad gullies with steep, smooth sides. Down three of them it was impossible to go except with the use of the second rope, which in each instance was carefully adjusted around a knob of rock at the top, so that it could be withdrawn by the last man. We regained the snow at the point where we had left the knapsacks and ice-axes, and once on it realized that we would have to make haste, for it was very warm and some three hundred feet of the route were likely at any moment to be swept by avalanches from the steep glacier which came down from the Aiguille de la Blaitiere. Across this space we hurried in double quick step and without further incident reached the Rognon at 1.30 and Montanvert at 4. The climb proved to be one of the best and most exciting I have ever enjoyed and also the last one of this my fifteenth season in the Alps.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches My Summer in the Alps, 1913