V. PERIOD OF GREAT ENDEAVOUR

We have now reached the most important period in our painter’s career, coinciding from end to end with his residence in the Flemish capital, where he died on the 9th of July 1441 — a period of over ten years, in which he produced the ten dated masterpieces we are about to review, besides a large unfinished triptych and a number of other paintings to which no exact date can be affixed. Hardly had he taken up his quarters in Bruges than the Duke summoned him to Hesdin to receive instructions with regard to the work on which he was to be employed. Meanwhile, no doubt, Jodoc Vyt had secured his services for the completion of the Ghent Polyptych: probably it had been an understood thing all along that John was to finish the work at the first opportunity. From the account of his movements during the five years that had elapsed since his brother’s death it is obvious that he could have spared but very brief intervals of leisure for what must, after all, have been to him a labour of love; the conclusion being that whatever proportion of the sixteen months immediately following his return from Portugal he was able to devote to the picture must stand for his share in the monumental altar-piece that at Hubert’s death had already been ten years in the making.

PLATE VII.— PORTRAIT OF MARGARET VAN EYCK THE PAINTER’S WIFE (By John van Eyck) The daughter of the subject of Plate IV. and probably the sister of Joan Cenani in Plate V., with both of which it should be compared. In the Town Gallery, Bruges. See page 76.

In the early days of December 1431 Cardinal Albergati, special ambassador from Pope Martin V. to the Courts of France, Burgundy, and England with a view to bringing about a general peace, spent three days at the Charterhouse in Bruges as the honoured guest of the Duke, from whom Van Eyck received urgent instructions to paint the portrait that is now the property of the Imperial Gallery at Vienna. The time being all too short for the purpose, John had to be content with the exquisite drawing in silver-point on a white ground which is still preserved in the Royal Cabinet of Prints at Dresden, and which is particularly interesting because of the marginal memoranda in pencil embodying the most minute observations in the artist’s own handwriting for his guidance in the execution of the painting. A remarkable portrait of a most remarkable man: for this prince of the Church, a humble son of the austere Order of the Carthusians, though raised to the Cardinalate and time after time called upon to serve the Holy See on important embassies requiring consummate prudence in regard to matters of temporal policy, discarding his family arms for a simple cross, persevered to the end in such austerities of the cloister as the wearing of a hair shirt, total abstinence from flesh-meat, and the use of bare straw for his rude pallet: a type that must have appealed to Van Eyck, for the picture is a valuable index of the painter’s genius for portraiture. In or about August of the following year the Burgomasters and Town Council honoured John with a visit to his workshop, to inspect the various pictures he was then engaged on. Among these, probably, was the portrait of „Tymotheos,“ bearing date October 10, 1432, acquired by the National Gallery in 1857 for the modest sum of £189, lis. (Plate III.), and the „Our Lady and Child” in the collection at Ince Hall, Ince Blundell, Liverpool, although it was not completed till 1433. The latter is a delightful instance of the singular love of domesticity which Van Eyck exemplifies with supreme confidence and success in the Arnolfini tableau, of which more anon. In the former we have a man verging on middle age, with dark complexion, blue eyes, angular features, heavy jaw, thick lips, prominent cheek-bones and uplifted nose; presumably a Greek humanist and a friend of the painter, from the man’s Christian name on the parapet being in Greek character and the manuscript roll he holds in his hand, and from the inscription „Léal Souvenir”: by no means a handsome type, but true to nature, and presented with all the charm that Van Eyck was able to endow his least promising subjects with, the modelling being excellent, and the harmonious colouring aptly relieved by a dark background.

Somewhere about this time John’s thoughts, somewhat later in life than was the custom ot the age, must have been turning on matrimony on his own account, for we find him purchasing a house in the parish of Saint Giles, a quarter much affected by painters, and shortly afterwards engaged on a portrait of the man appointed to be his father-in-law; and we can picture the Duke, with whom he was ever a special favourite, being made the confidant of his intentions on the occasion of his visit to Van Eyck’s workshop on the 19th of February 1433, and pleasantly encouraging him with a promise to stand sponsor for his first-born. At any rate the wedding took place, and in due course Sir Peter de Beaufremont, Lord of Chargny, held the infant at the baptismal font as proxy for Philip, whose present took the form of six silver cups weighing 12 marks, the order for payment of the account, amounting to 96 L. 12s., to a local goldsmith, John Peutin, bearing date June 30, 1434; and this is the nearest approach we can get at to the date of either event. Indeed, we have no information as to the sex of the child, nor are we even acquainted with the maiden name of Van Eyck’s wife, though it has been suggested, with some show of reason, that she was a sister of Joan Cenani, the wife of John Arnolfini, already referred to; and it is only within quite recent days that the painting in the National Gallery commonly spoken of as „the man with the turban” has been identified, on purely scientific lines, as the portrait of her father. If the reader will compare this likeness (Plate IV.) with that of Margaret van Eyck (Plate VII.) he must immediately be struck by the close resemblance that irresistibly suggests the relationship: the marvel is that the absolute identity of features in the two portraits escaped notice so long. The fanciful style of head-dress, except it was intended to symbolise occupation or profession, remains a puzzle; for it is difficult to conceive a man of his earnest and dignified disposition masquerading in strange attire for the mere sake of effect. The best authorities speak of him as a well-to-do merchant — specialising perhaps in Eastern wares, such as crowded the marts of the Flemish capital in the heyday of its prosperity — apparently about sixty-five years of age, the face being delicately painted in reddish-brown tones, and showing every detail with uttermost faithfulness, even to the pleats of the eyelids and at the root of the nose, and to every vein and wrinkle of the forehead. It is one of the finest exemplifications of John’s rare gift of portraiture, the pleasing modesty of the artist — as revealed in the inscription „Als ich kan“ (to the best of my ability) — adding, indeed, to the charm of the picture, which bears date October 21, 1433, and passed into the keeping of the National Gallery in 1851 for the sum of £315.

It is difficult to refrain from what would appear an over-use of the superlative in dealing with John van Eyck’s works, but if the writer might be allowed an indulgence he would unhesitatingly avail himself of it to the full in connection with the exquisite panel (Plate V.) for the possession of which we are indebted to the honourable wounds which were the seal of Major-General Hay’s part in the battle of Waterloo. After wandering about Europe as the cherished possession first of Don Diego de Guevara, councillor of Maximilian and Archduke Charles and Major-domo of Joan, Queen of Castile; next of Margaret of Austria, Governess of the Netherlands; subsequently of Mary of Hungary, and eventually of Charles III. of Spain, it fell into the acquisitive hands of the French invader of the Peninsula, and by some strange freak of fortune strayed to the apartments at Brussels in which the gallant major-general was nursed to recovery, from whose landlord he purchased it, the National Gallery in the end becoming its owner, in 1842, for the trifling sum of £730. It is the picture of a newly married couple in a homely Flemish interior, and in their attempts to solve an imaginary riddle critics have given their somewhat prolific powers of imagination an unusually free rein. For instance, the peculiar manner in which the bride sustains the gathered folds of her skirt — shown by comparison with figures of virgin saints in other of Van Eyck’s paintings to have been a passing fashion of the day, if an ungraceful one — suggested to some the near approach of her lying-in, the bedstead in the background as well as the figure of St. Margaret (a favourite of women in expectation of childbirth) surmounting the back of the armchair naturally tending to confirm the impression; in corroboration of which the attitude of husband and wife— though the direction of look in neither lends support to the theory— is explained as a venture in chiromancy, the adept bridegroom endeavouring to read in the lines of his wife’s hand the future of the coming infant: a variant elucidation representing the husband as solemnly protesting his paternity to an inexistent crowd of neighbours at the open door, seeing that the ingenious reflection of the scene in the circular convex mirror on the far wall reveals but two additional figures, probably the painter and his apprentice. Without recourse to fancy, the attitude of bridegroom and bride, hand in hand, might readily have been seen to symbolise the perfect union begot of a happy marriage. John’s love of domesticity is abundantly displayed in all the detail of the work — the chandelier, with lighted taper, dependent from the ceiling, the aumbry with its couple of oranges, the cushioned bench by the window, the dainty pair of red shoes on the carpet by the bedside, the pattens of white wood with black leather latchets in the foreground, even to the dusting-brush hung on the arm-chair, and the pet griffin terrier, all helping to heighten the intimacy of the scene; while the cherry-tree in full bloom, seen through the open window against a sky of clear blue, serves to fix the season of the year in which the picture was painted. The portraits are of John Arnolfini and Joan Cenani: the former, in later years, was knighted and appointed a chamberlain at his court by Duke Philip, and from the circumstance of his burial in the chapel of the Lucchese merchants at the Austin Friars’ we may presume both his nationality and calling; the latter, considered in respect of certain features, especially the eyes, eyebrows, and nose, suggests a sufficient likeness to warrant the surmise that she was a younger sister of Van Eyck’s wife. The panel, which is in an almost perfect state of preservation, is a fine example of the painter’s vigour of delineation and perfect blending of colour, both as regards the interior and the figures, the transparency of shadow in the fleshtints showing the utmost delicacy of touch. The picture bears date 1434.

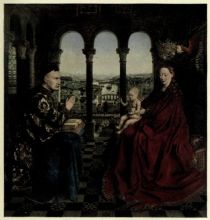

PLATE VIII.— THE VIRGIN AND CHILD, AND CHANCELLOR ROLIN (By — van Eyck) Whether the work of Hubert or of John is still in dispute: hence an interesting example for the critical student of their respective arts. Nicholas Rolin was born in 1376, was created Chancellor of Burgundy and Brabant on December 3, 1422, and died January 18, 1462. The landscape in the background is distinctly reminiscent of the scenery about Maastricht, the alma mater of the Van Eycks. The general effect of the picture is marred by an unpleasant coating of yellow varnish. Date uncertain. In the Louvre, Paris. See page 78.

About this time Van Eyck was once more in trouble with the Receiver of Flanders and his officials. Philip, adding one more to the many marks of favour reserved for his predilect painter, had bestowed on him a life-pension of 4320 L. in lieu of the salary of l00 L. parisis awarded him at the time of his engagement. In the absence of any explanation of this enormous increase, the mystified accountants at Lille declined registration of the letters patent; but they were speedily brought to their senses by John’s threat, without further waste of words, to throw up his appointment there and then: so they referred the matter back to the Duke, who by letters of March 12, 1435, commanded immediate registration of the patent and payment of the pension under penalty of his extreme displeasure, pro- testing that, being about to employ Van Eyck on works of the highest importance, he „could not find another painter equally to his taste or of such excellence in his art and science.“ Matters being thus satisfactorily composed, John was free to attend to his patron’s behests; in addition to which he had the gilding and polychroming in 1435 of six of the eight statues of counts and countesses of Flanders executed by local sculptors for the front of the new Townhouse, probably from his own designs. Yet another present of six silver cups, perhaps as a salve for his wounded feelings, and employment on a further secret mission to distant parts in 1436 testify to the Duke’s abiding trust and approbation. These undertakings, however, did not exhaust the painter’s marvellous capacity for work, for this year also witnessed the completion of one of the largest of his pictures, the altar-piece to the order of Canon Van der Paele, for the collegiate church of Saint Donatian at Bruges (Plate VI.), which since its recovery from the French in 1815 has graced the collection of the local Town Gallery. John’s love of the Romanesque probably accounts for his neglect of the architecture of that church in designing the apse of the transept in which the Virgin and Child sit enthroned, but the scenic effect produced by his treatment of the series of round arches on cylindrical columns and of the pillared ambulatory goes far to compensate for the omission; the beauty of the picture being further enhanced by the ornate carving of the capitals and throne, the gorgeous display of cloth-of-gold and tapestry, and the rich variety of dress and costume, culminating in all the splendour of the archiepiscopal vestments, yet not so overpowering as to dwarf interest in the noble countenance of the wearer. Howbeit, the artist was singularly unfortunate in the subjects appointed to pose for the Virgin and St. George, while the Divine Child is probably the least pleasing of his Infant Christs. St. Donatian, however, and the homely yet dignified ecclesi- astic typified as the Donor, largely redeem the figure-work from the charge of insignificance. It would appear that the life-size bust of Canon Van der Paele at Hampton Court Palace was a study for the full-length portrait, for at the time the altar-piece was being executed the worthy Canon was already so feeble that since September 1434 he had been dispensed by the Chapter from attendance in choir on the score of infirmity and advanced age.

The „Portrait of John De Leeuw, goldsmith,“ in the Imperial Gallery at Vienna (1436), and two charming pictures in the Antwerp Museum— „Saint Barbara“ (1437) and the „Our Lady and Child by a Fountain” (1439)— come next in order of the artist’s dated pieces, the series closing with the „Portrait of Margaret van Eyck“ (Plate VII.) in the Town Gallery at Bruges, which bears date June 17, 1439: a work of marvellous delicacy and finish, and a tribute of love worthy alike of the painter-husband and his devoted wife; the latter an intelligent type of the competent Flemish housewife, clear and steady of eye and firm of mouth, portrayed with infinite minuteness and not the least concession to vanity. Formerly the property of the Guild of Painters and Saddlers, it used annually to be exhibited in their chapel on St. Luke’s Day, amply secured, if we believe the popular legend, with chain and padlock, because of the companion picture. Van Eyck’s own portrait, having been stolen through lack of similar precautions.

The sad loss to Art sustained by John van Eyck’s death on the 9th of July 1441 is accentuated by the unfinished state in which he left the great triptych on which he was engaged for Nicholas van Maelbeke, Provost of Saint Martin’s at Ypres, his largest painting and, had he but lived to complete it, in every respect his masterpiece. As a member of the Duke’s household John was buried within the precincts of the collegiate church of St. Donatian, and his remains finally laid to rest some months later within the building, near the font; and an anniversary Requiem Mass, founded at the time, continued to be celebrated until the French invasion in 1792. In death as in life Duke Philip never forgot his faithful friend and servant: within a few days of his decease he sought to solace the widow’s grief with a gratuity of 360 L. in token of his appreciation of the great master whose death they all mourned, and years after he graciously assisted Livina, the one surviving child of the marriage, and a sister of his own godchild, to enter the Convent of St. Agnes at Maaseyck.

PLATE VII.— PORTRAIT OF MARGARET VAN EYCK THE PAINTER’S WIFE (By John van Eyck) The daughter of the subject of Plate IV. and probably the sister of Joan Cenani in Plate V., with both of which it should be compared. In the Town Gallery, Bruges. See page 76.

In the early days of December 1431 Cardinal Albergati, special ambassador from Pope Martin V. to the Courts of France, Burgundy, and England with a view to bringing about a general peace, spent three days at the Charterhouse in Bruges as the honoured guest of the Duke, from whom Van Eyck received urgent instructions to paint the portrait that is now the property of the Imperial Gallery at Vienna. The time being all too short for the purpose, John had to be content with the exquisite drawing in silver-point on a white ground which is still preserved in the Royal Cabinet of Prints at Dresden, and which is particularly interesting because of the marginal memoranda in pencil embodying the most minute observations in the artist’s own handwriting for his guidance in the execution of the painting. A remarkable portrait of a most remarkable man: for this prince of the Church, a humble son of the austere Order of the Carthusians, though raised to the Cardinalate and time after time called upon to serve the Holy See on important embassies requiring consummate prudence in regard to matters of temporal policy, discarding his family arms for a simple cross, persevered to the end in such austerities of the cloister as the wearing of a hair shirt, total abstinence from flesh-meat, and the use of bare straw for his rude pallet: a type that must have appealed to Van Eyck, for the picture is a valuable index of the painter’s genius for portraiture. In or about August of the following year the Burgomasters and Town Council honoured John with a visit to his workshop, to inspect the various pictures he was then engaged on. Among these, probably, was the portrait of „Tymotheos,“ bearing date October 10, 1432, acquired by the National Gallery in 1857 for the modest sum of £189, lis. (Plate III.), and the „Our Lady and Child” in the collection at Ince Hall, Ince Blundell, Liverpool, although it was not completed till 1433. The latter is a delightful instance of the singular love of domesticity which Van Eyck exemplifies with supreme confidence and success in the Arnolfini tableau, of which more anon. In the former we have a man verging on middle age, with dark complexion, blue eyes, angular features, heavy jaw, thick lips, prominent cheek-bones and uplifted nose; presumably a Greek humanist and a friend of the painter, from the man’s Christian name on the parapet being in Greek character and the manuscript roll he holds in his hand, and from the inscription „Léal Souvenir”: by no means a handsome type, but true to nature, and presented with all the charm that Van Eyck was able to endow his least promising subjects with, the modelling being excellent, and the harmonious colouring aptly relieved by a dark background.

Somewhere about this time John’s thoughts, somewhat later in life than was the custom ot the age, must have been turning on matrimony on his own account, for we find him purchasing a house in the parish of Saint Giles, a quarter much affected by painters, and shortly afterwards engaged on a portrait of the man appointed to be his father-in-law; and we can picture the Duke, with whom he was ever a special favourite, being made the confidant of his intentions on the occasion of his visit to Van Eyck’s workshop on the 19th of February 1433, and pleasantly encouraging him with a promise to stand sponsor for his first-born. At any rate the wedding took place, and in due course Sir Peter de Beaufremont, Lord of Chargny, held the infant at the baptismal font as proxy for Philip, whose present took the form of six silver cups weighing 12 marks, the order for payment of the account, amounting to 96 L. 12s., to a local goldsmith, John Peutin, bearing date June 30, 1434; and this is the nearest approach we can get at to the date of either event. Indeed, we have no information as to the sex of the child, nor are we even acquainted with the maiden name of Van Eyck’s wife, though it has been suggested, with some show of reason, that she was a sister of Joan Cenani, the wife of John Arnolfini, already referred to; and it is only within quite recent days that the painting in the National Gallery commonly spoken of as „the man with the turban” has been identified, on purely scientific lines, as the portrait of her father. If the reader will compare this likeness (Plate IV.) with that of Margaret van Eyck (Plate VII.) he must immediately be struck by the close resemblance that irresistibly suggests the relationship: the marvel is that the absolute identity of features in the two portraits escaped notice so long. The fanciful style of head-dress, except it was intended to symbolise occupation or profession, remains a puzzle; for it is difficult to conceive a man of his earnest and dignified disposition masquerading in strange attire for the mere sake of effect. The best authorities speak of him as a well-to-do merchant — specialising perhaps in Eastern wares, such as crowded the marts of the Flemish capital in the heyday of its prosperity — apparently about sixty-five years of age, the face being delicately painted in reddish-brown tones, and showing every detail with uttermost faithfulness, even to the pleats of the eyelids and at the root of the nose, and to every vein and wrinkle of the forehead. It is one of the finest exemplifications of John’s rare gift of portraiture, the pleasing modesty of the artist — as revealed in the inscription „Als ich kan“ (to the best of my ability) — adding, indeed, to the charm of the picture, which bears date October 21, 1433, and passed into the keeping of the National Gallery in 1851 for the sum of £315.

It is difficult to refrain from what would appear an over-use of the superlative in dealing with John van Eyck’s works, but if the writer might be allowed an indulgence he would unhesitatingly avail himself of it to the full in connection with the exquisite panel (Plate V.) for the possession of which we are indebted to the honourable wounds which were the seal of Major-General Hay’s part in the battle of Waterloo. After wandering about Europe as the cherished possession first of Don Diego de Guevara, councillor of Maximilian and Archduke Charles and Major-domo of Joan, Queen of Castile; next of Margaret of Austria, Governess of the Netherlands; subsequently of Mary of Hungary, and eventually of Charles III. of Spain, it fell into the acquisitive hands of the French invader of the Peninsula, and by some strange freak of fortune strayed to the apartments at Brussels in which the gallant major-general was nursed to recovery, from whose landlord he purchased it, the National Gallery in the end becoming its owner, in 1842, for the trifling sum of £730. It is the picture of a newly married couple in a homely Flemish interior, and in their attempts to solve an imaginary riddle critics have given their somewhat prolific powers of imagination an unusually free rein. For instance, the peculiar manner in which the bride sustains the gathered folds of her skirt — shown by comparison with figures of virgin saints in other of Van Eyck’s paintings to have been a passing fashion of the day, if an ungraceful one — suggested to some the near approach of her lying-in, the bedstead in the background as well as the figure of St. Margaret (a favourite of women in expectation of childbirth) surmounting the back of the armchair naturally tending to confirm the impression; in corroboration of which the attitude of husband and wife— though the direction of look in neither lends support to the theory— is explained as a venture in chiromancy, the adept bridegroom endeavouring to read in the lines of his wife’s hand the future of the coming infant: a variant elucidation representing the husband as solemnly protesting his paternity to an inexistent crowd of neighbours at the open door, seeing that the ingenious reflection of the scene in the circular convex mirror on the far wall reveals but two additional figures, probably the painter and his apprentice. Without recourse to fancy, the attitude of bridegroom and bride, hand in hand, might readily have been seen to symbolise the perfect union begot of a happy marriage. John’s love of domesticity is abundantly displayed in all the detail of the work — the chandelier, with lighted taper, dependent from the ceiling, the aumbry with its couple of oranges, the cushioned bench by the window, the dainty pair of red shoes on the carpet by the bedside, the pattens of white wood with black leather latchets in the foreground, even to the dusting-brush hung on the arm-chair, and the pet griffin terrier, all helping to heighten the intimacy of the scene; while the cherry-tree in full bloom, seen through the open window against a sky of clear blue, serves to fix the season of the year in which the picture was painted. The portraits are of John Arnolfini and Joan Cenani: the former, in later years, was knighted and appointed a chamberlain at his court by Duke Philip, and from the circumstance of his burial in the chapel of the Lucchese merchants at the Austin Friars’ we may presume both his nationality and calling; the latter, considered in respect of certain features, especially the eyes, eyebrows, and nose, suggests a sufficient likeness to warrant the surmise that she was a younger sister of Van Eyck’s wife. The panel, which is in an almost perfect state of preservation, is a fine example of the painter’s vigour of delineation and perfect blending of colour, both as regards the interior and the figures, the transparency of shadow in the fleshtints showing the utmost delicacy of touch. The picture bears date 1434.

PLATE VIII.— THE VIRGIN AND CHILD, AND CHANCELLOR ROLIN (By — van Eyck) Whether the work of Hubert or of John is still in dispute: hence an interesting example for the critical student of their respective arts. Nicholas Rolin was born in 1376, was created Chancellor of Burgundy and Brabant on December 3, 1422, and died January 18, 1462. The landscape in the background is distinctly reminiscent of the scenery about Maastricht, the alma mater of the Van Eycks. The general effect of the picture is marred by an unpleasant coating of yellow varnish. Date uncertain. In the Louvre, Paris. See page 78.

About this time Van Eyck was once more in trouble with the Receiver of Flanders and his officials. Philip, adding one more to the many marks of favour reserved for his predilect painter, had bestowed on him a life-pension of 4320 L. in lieu of the salary of l00 L. parisis awarded him at the time of his engagement. In the absence of any explanation of this enormous increase, the mystified accountants at Lille declined registration of the letters patent; but they were speedily brought to their senses by John’s threat, without further waste of words, to throw up his appointment there and then: so they referred the matter back to the Duke, who by letters of March 12, 1435, commanded immediate registration of the patent and payment of the pension under penalty of his extreme displeasure, pro- testing that, being about to employ Van Eyck on works of the highest importance, he „could not find another painter equally to his taste or of such excellence in his art and science.“ Matters being thus satisfactorily composed, John was free to attend to his patron’s behests; in addition to which he had the gilding and polychroming in 1435 of six of the eight statues of counts and countesses of Flanders executed by local sculptors for the front of the new Townhouse, probably from his own designs. Yet another present of six silver cups, perhaps as a salve for his wounded feelings, and employment on a further secret mission to distant parts in 1436 testify to the Duke’s abiding trust and approbation. These undertakings, however, did not exhaust the painter’s marvellous capacity for work, for this year also witnessed the completion of one of the largest of his pictures, the altar-piece to the order of Canon Van der Paele, for the collegiate church of Saint Donatian at Bruges (Plate VI.), which since its recovery from the French in 1815 has graced the collection of the local Town Gallery. John’s love of the Romanesque probably accounts for his neglect of the architecture of that church in designing the apse of the transept in which the Virgin and Child sit enthroned, but the scenic effect produced by his treatment of the series of round arches on cylindrical columns and of the pillared ambulatory goes far to compensate for the omission; the beauty of the picture being further enhanced by the ornate carving of the capitals and throne, the gorgeous display of cloth-of-gold and tapestry, and the rich variety of dress and costume, culminating in all the splendour of the archiepiscopal vestments, yet not so overpowering as to dwarf interest in the noble countenance of the wearer. Howbeit, the artist was singularly unfortunate in the subjects appointed to pose for the Virgin and St. George, while the Divine Child is probably the least pleasing of his Infant Christs. St. Donatian, however, and the homely yet dignified ecclesi- astic typified as the Donor, largely redeem the figure-work from the charge of insignificance. It would appear that the life-size bust of Canon Van der Paele at Hampton Court Palace was a study for the full-length portrait, for at the time the altar-piece was being executed the worthy Canon was already so feeble that since September 1434 he had been dispensed by the Chapter from attendance in choir on the score of infirmity and advanced age.

The „Portrait of John De Leeuw, goldsmith,“ in the Imperial Gallery at Vienna (1436), and two charming pictures in the Antwerp Museum— „Saint Barbara“ (1437) and the „Our Lady and Child by a Fountain” (1439)— come next in order of the artist’s dated pieces, the series closing with the „Portrait of Margaret van Eyck“ (Plate VII.) in the Town Gallery at Bruges, which bears date June 17, 1439: a work of marvellous delicacy and finish, and a tribute of love worthy alike of the painter-husband and his devoted wife; the latter an intelligent type of the competent Flemish housewife, clear and steady of eye and firm of mouth, portrayed with infinite minuteness and not the least concession to vanity. Formerly the property of the Guild of Painters and Saddlers, it used annually to be exhibited in their chapel on St. Luke’s Day, amply secured, if we believe the popular legend, with chain and padlock, because of the companion picture. Van Eyck’s own portrait, having been stolen through lack of similar precautions.

The sad loss to Art sustained by John van Eyck’s death on the 9th of July 1441 is accentuated by the unfinished state in which he left the great triptych on which he was engaged for Nicholas van Maelbeke, Provost of Saint Martin’s at Ypres, his largest painting and, had he but lived to complete it, in every respect his masterpiece. As a member of the Duke’s household John was buried within the precincts of the collegiate church of St. Donatian, and his remains finally laid to rest some months later within the building, near the font; and an anniversary Requiem Mass, founded at the time, continued to be celebrated until the French invasion in 1792. In death as in life Duke Philip never forgot his faithful friend and servant: within a few days of his decease he sought to solace the widow’s grief with a gratuity of 360 L. in token of his appreciation of the great master whose death they all mourned, and years after he graciously assisted Livina, the one surviving child of the marriage, and a sister of his own godchild, to enter the Convent of St. Agnes at Maaseyck.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches VAN EYCK MASTERPIECES

VII. Portrait of Margaret van Eyck, the Painters Wife, 1439 (By John van Eyck.— Town Gallery, Bruges)

VIII. The Virgin and Child, and Chancellor Rolin, date uncertain (By — van Eyck.— The Louvre, Paris)

alle Kapitel sehen