III. THE GREAT POLYPTYCH

So, back to Maaseyck and to Maastricht: to family rejoicings and the generous welcome of old friends, no light matter when ordered on the good old Netherlandish scale. Anxiety there, of course, and much curiosity here, as to how the promise of early talent would be justified by the ripening fruit. Nor could the issue have been long in doubt. The indispensable test triumphantly passed, the customary formalities duly complied with, and Hubert van Eyck took his place among the master painters of his time, soon to claim rank among the élite of them all. Of wife or children not a whisper, but in an age when civism spelt patriotism, and marriage was recognised as one of the prime moral obligations of a loyal citizen, it is inconceivable that a man of his sterling sense of duty should have done other than conform to the established practice. His home and workshop were from the outset probably cheered by the presence of his younger brother John, fired by the born artist’s enthusiasm to follow in his senior’s footsteps. This Maastricht studio no doubt also witnessed the inception of that long series of experiments, secretly shared in by the two brothers until carried to perfection, which gave to the world the new art of oil-painting, and so laid all the after ages under the deepest obligation to them.

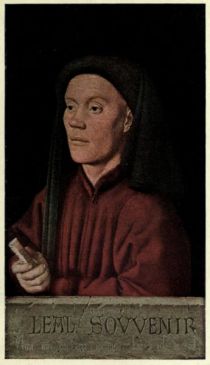

PLATE III.— PORTRAIT OF “TYMOTHEOS“ (By John van Eyck)

A Presentation Portrait, probably from the Painter to his friend „Timothy,“ a Greek humanist whose Christian name only is known. The inscription at the foot reads: „Actum anno Domini 1432, 10 die Octobris, a Johanne de Eyck.“ No. 290 in the National Gallery, London. See pages 63, 64.

John’s apprenticeship ended, and he in turn started on his travels, Hubert would appear to have removed to Holland, where painters and miniaturists of the early years of the fifteenth century repeatedly exhibit marked traces of his influence; where also miniatures in a Book of Hours, of date 1412 to 1417, to the order of Count William for the use of his only daughter, the fair and ill-starred Jacqueline, are judged to have been executed by him on the strength of the many points of resemblance they bear to the Great Polyptych. The commission of the latter work itself is now confidently attributed to the same prince. Observe the prominence given to the tower of Saint Martinis at Utrecht and the adjacent view of Coin in the centre-piece, „The Adoration of the Lamb,“ and to St. Martin himself, the patron saint of Utrecht, in the panel of „The Knights of Christ,“ the banner in his grasp, moreover, charged with the arms of that town: the Counts territory was in the diocese of Utrecht and the ecclesiastical province of Coin. So much depends on the origin of this commission in apportioning the respective share each of the brothers had in its execution that the further fact must not be overlooked that Ghent, for which the great work was completed, had no sort of connection with either Utrecht or Coini being in the diocese of Tournay and the ecclesiastical province of Rheims, while the only saint in the altar-piece specially connected with Ghent who is characterised by an emblem — St. Livin, to wit — was also widely venerated in Zeeland. Finally, not to labour this aspect of the question unduly, the inscription on the frame attributes, not the picture’s inception, but its completion, to Jodoc Vyt, the eventual donor — a form of words so singular as to admit of no other interpretation than the plain meaning the expression conveys.

Count William passed away on the 31st of May 1417, leaving an only child, Jacqueline, aged seventeen, by his wife, Margaret of Burgundy, who had predeceased him. Her uncle, John of Bavaria, Prince-Bishop of Liège, an unscrupulous ruffian who clearly paid small deference to women’s rights, at once set himself to rob the unfortunate princess of her possessions. In September 1418 he marched out on Dordrecht, where he established his headquarters; Gorcum and other strongholds speedily succumbed to his arms, and after an interval, during which he married Elizabeth of Gorlitz, Duchess of Luxemburg and widow of Anthony of Burgundy, Duke of Brabant and Limburg, he finally removed to Holland and installed himself at The Hague, free now to pursue his nefarious projects. For thirteen years the country resounded with the clash of arms and laboured in the rough and tumble of civil warfare: hence an atmosphere the least congenial to the cultivation and patronage of high art. The cities of Flanders and Brabant were the gainers by the exodus of craftsmen that presently set in. Of their number, sooner or later, was Hubert, who, prior to 1425 at any rate, had already settled at Ghent and acquired the freedom of that city. News of the unfinished polyptych remaining on his hands soon came to the ears of Jodoc Vyt, a wealthy burgher, who eagerly embraced the opportunity of striking the bargain by which he acquired all rights in the picture and so linked his name and personality for all time with this ineffable monument of the painter’s art.

In the centre-piece, „The Adoration of the Lamb“ (frontispiece), we discover the keynote to the scheme of the work, in the Apocalyptic Vision of St. John the source of its inspiration. The Lamb without spot, the blood from its breast pouring into a chalice, is stood on an altar, the white cloth over which bears on its superfrontal the text from the Vulgate, „Behold the Lamb of God, who taketh away the sins of the world,” and on its stole-ends the legend, „Jesus, the Way, the Truth, and the Life.” Worshipping angels gather around, some bearing instruments of the Passion, others swinging censers, their smoke laden with the prayers of the saints. In the foreground the Fountain of Life, flowing down through the ages along the gentle slope of flower-bejewelled sward, or dispensing its waters in vivifying jets from the gurgoyles beneath the feet and from the vases in the hands of the winged angel above its standard. To the four quarters groups of the elect: on the near right those of the Old Law and among the Gentiles who had lived in expectation of the Redeemer, the balancing group on the left typical of the New Law — prophets, doctors, philosophers, and princes in the former, the Apostles, popes, bishops, abbots, deacons, monks, and clerics among the latter. The corresponding groups back of the altar represent the army of martyrs whose blood is the seed of the Church, and the multitude of virgins. Over all, from the Holy Dove poised high over the altar, dart rays of light, emblematic of the Wisdom which had inspired their lives and of the fire of Love that had heartened their sacrifice. A carpet of flowers fills in all the open space fore of the altar, flowering shrubs and trees that of the middistance, while the entire background is an exquisite example of the realistic landscape-work that is an abiding charm of the Netherlandish school. The wonderful harmony of colour appeals at once to the senses; but more arresting, on nearer acquaintance, for its quality and felicity, is the wide range of portraiture that distinguishes the piece. From the two lateral panels in the dexter shutter the Knights of Christ and the Just Judges are pressing forward to the scene of the Vision, from the corresponding ones in the sinister shutter the Holy Hermits and the Holy Pilgrims: the former on spirited horses — an animal for whichthe painter evinces a special affection — the latter on foot. These panels are even more remarkable perhaps than the centre-piece for the diversity and multiplicity of the types portrayed, and for the wealth of landscape relieved by bird life lavished in their embellishment

The „Adoration of the Lamb” is dominated in the upper zone by a triple panel, the centre framing the Almighty enthroned in majesty, whose is the kingdom, the power, and the glory — a supreme conception of the Eternal Father, unequalled for majestic stillness of face, intellectual power of brow, and depth and placidity of vision; on His right is the Mother of Christ, testifying to the full the lowliness of the handmaiden of the Lord, on His left St. John the Baptist, an earnest type, long of hair and rugged of beard, barefooted, and in a raiment of brown camel’s hair girdled about the loins, intensifying the austerity of life ordained for him who was to prepare the way of the Lord and make straight His paths. In the „Choir of Angels“ (Plate II.), which is the subject of the first lateral panel in the dexter shutter, we have one of the choicest gems of the polyptych, and it affords us a measure of the distance the realistic tendencies of the painter had carried him from the traditions of the mystic school. Justified by the warrant of Scripture, he translates these spirit beings into purely human frames, but with a nerve system attuned to material sensations. In these angels there is no suggestion of trance-like ecstasy in contemplation of the Beatific Vision; they are angels materialised whose features reflect the strain of sustained effort and the underlying sense of pain which in man is inseparable from the sensing of intense joy. Evidently the master had fathomed the secrets of the human heart: the sense possibilities of the spirit world were without his ken, so he humanised his angels and evolved types understandable of the people, and at the same time one of the finest angel groups of all art. So inexpressibly realistic are his conceptions that to the poet-biographer Van Mander, at any rate, it was actually possible to discern „the different key in which the voice of each is pitched.“ But poets are privileged beings. Accompanying the Choir in their song of praise with organ, harp, and viol are the balancing group of angels in the corresponding compartment of the sinister shutter, types that, strangely enough, are in striking contrast to the former, their features moulded in placid contentment. The extreme panels of this zone are occupied by life-size presentations of our First Parents after the Fall, nude figures painted from the life, with absolute fidelity to nature and masterly conception of type: in a demilunette over the figure of Adam we see Cain and Abel making their offerings unto the Lord, and in that over Eve the slaying of Abel at the hands of his brother. There is a tradition extant that the altar-piece was originally furnished with a predella painted in distemper, a picture probably of Limbo or of Purgatory, but no trace of this remains.

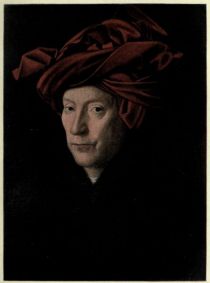

PLATE IV.— PORTRAIT OF THE PAINTER’S FATHER-IN-LAW (By John van Eyck)

The subject of this painting has only within recent months been identified as the father of Margaret van Eyck, with whose portrait, reproduced in Plate VII., it should be compared. The framework bears along the upper border the Painter’s simple motto “Als ich can,“ and at the foot „Johannes de Eyck me fecit anno 1433, 21 Octobris.“ No. 222 in the National Gallery, London. See page 76.

The closed shutters display, filling in the full width of the middle zone, the scene of the Annunciation. The Ethyrean Sibyl and the Cumaean Sibyl occupy the demi-lunettes above the middle portion of the Virgin’s chamber, the lunettes above the lateral divisions showing half-length figures of the Prophets Zacharias and Micheas. Of the four compartments of the lower zone the inner ones contain statues in grisaille of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, the outer ones figures in the attitude of prayer, eminently life-like, of the donor, Jodoc Vyt, and his wife, Elizabeth Borluut. Jodoc was the second son of Sir Nicholas Vyt, Receiver of Flanders, — a wealthy citizen who owned the lordships of Pamele and Leedberghe, besides several mansions in Ghent, of which city he was burgomaster in 1433-34, after filling various minor municipal offices: by no means a handsome type, though manifestly a capable and kindly burgher, well-set, with a somewhat low forehead, small grey eyes, and a large mouth with broad under-lip; neither do the shortcropped hair and growing baldness or the three warts on upper-lip, nose, and forehead make for attractiveness. In respect of looks his wife is the better favoured, striking the beholder as an indulgent lady, with much of the homely dignity and serenity of the finer type of Flemish matron.

The Great Polyptych had not yet reached completion when, on the 18th of September 1426 Hubert van Eyck passed away after a painful illness. How much of the work remained to be accomplished none can tell with any hope of approach to certainty. A whole volume would not suffice for a critical examination of the mass of contending theories that for the best part of a century has been squandered in the endeavour to allocate to the two brothers their respective shares in the execution of the picture. Remember that it had already been some ten years in the making, and that, although it did not receive its final touches from the brush of John van Eyck until 1432, nearly six years after his brother’s death, this period of John’s life, as we shall presently discover, was too fully occupied in the service of Duke Philip of Burgundy to have allowed of his spending any considerable proportion of it in the task of completion. Remembering also that John’s art had been closely modelled on that of his brother, that none better comprehended his ideals or was more intimately acquainted with the working out of his conceptions, mindful, moreover, of the deep veneration in which he held his master’s genius, we must suppose that he realised the obligation of conscientiously adhering to the art and technique of the picture as he found it, any obtruding originality in violation of which would have amounted almost to sacrilege: all this further enhances the difficulty of differentiating between the work of the two painters. Indeed, if so minded, the reader is probably as well equipped as the writer to solve the puzzle.

Hubert van Eyck was laid to rest in the crypt of the chapel for which he had painted his masterpiece, but in 1533, when chapel and crypt had to make way for a new aisle, his remains were transferred to the churchyard, all except the bone of the right fore-arm, which was suspended in an iron casket in the porch of the Cathedral. The brass plate bearing the well-known epitaph was at the same time placed in the transept, only to become the spoil of the Calvinist Iconoclasts in 1578, when already the casket had somehow or other long since disappeared. But what of the painter’s fame, to whose workshop laymen of the highest distinction had felt it a privilege to be admitted, about whose easel journeymen painters had flocked, and whom the leading contemporary artists of the Netherlands had been proud to call master? During his lifetime, and for a considerable period after his death, his was a domi-nating influence in the Art of the North, and Van Mander has it on record that whenever the polyptych was freely exposed to the public gaze crowds flocked to it from morning till night „like flies and bees in summer round a basket of figs and grapes.“ But in the stress and turmoil of succeeding generations his memory gradually faded away; his work, uncared for, lost hold on the imagination; even his great masterwork narrowly escaped destruction. Even so it did not escape dismemberment, or profanation at the hands of the „restorer.“ Saved from the fury of the Iconoclasts in 1566, and subsequently rescued from the Calvinist leaders who contemplated its offer to Queen Elizabeth in acknowledgment of her subsidies, it eventually became the spoil of the French Republicans; but after the battle of Waterloo restitution was effected, and the main portion of the altar-piece, all that remains of it in Ghent, was reinstated in its present position. The Adam and Eve panels, which in 1781 had offended the unsuspected modesty of Joseph II., and in consequence been deferentially removed, were ultimately ceded to the Belgian Government, and now rest in the Royal Gallery at Brussels; while the other six shutter panels, which had been safeguarded through the French occupation, were shamelessly sold to a dealer in 1816 by the Vicar-General and churchwardens — in the absence, it is right to say, of the Bishop — for a paltry 3000 florins, subsequently changing hands for 100,000 francs, and eventually becoming the property of the Prussian Government for four times that amount.

PLATE V.— JOHN ARNOLFINI AND JOAN CENANI, HIS WIFE (By John van Eyck)

An incomparable example of the Master’s varied gifts, and a valuable study of contemporary dress and domestic furniture. Joan Cenani is presumed to have been a younger sister of Margaret van Eyck, with whose portrait, reproduced in Plate VII., it should be compared. The carved frame of the mirror on the far wall enshrines ten small medallions, exquisite miniatures representing the Agony in the Garden, the Betrayal and St. Peter’s Assault on Malchus, Christ led before Pilate, the Scourging at the Pillar, the Carrying of the Cross, Calvary, the Deposition, the Entombment, the Descent into Limbo, and the Resurrection. On the wall above the mirror we read the precise statement, „Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434.“ No. 186 in the National Gallery, London. See page 67.

PLATE III.— PORTRAIT OF “TYMOTHEOS“ (By John van Eyck)

A Presentation Portrait, probably from the Painter to his friend „Timothy,“ a Greek humanist whose Christian name only is known. The inscription at the foot reads: „Actum anno Domini 1432, 10 die Octobris, a Johanne de Eyck.“ No. 290 in the National Gallery, London. See pages 63, 64.

John’s apprenticeship ended, and he in turn started on his travels, Hubert would appear to have removed to Holland, where painters and miniaturists of the early years of the fifteenth century repeatedly exhibit marked traces of his influence; where also miniatures in a Book of Hours, of date 1412 to 1417, to the order of Count William for the use of his only daughter, the fair and ill-starred Jacqueline, are judged to have been executed by him on the strength of the many points of resemblance they bear to the Great Polyptych. The commission of the latter work itself is now confidently attributed to the same prince. Observe the prominence given to the tower of Saint Martinis at Utrecht and the adjacent view of Coin in the centre-piece, „The Adoration of the Lamb,“ and to St. Martin himself, the patron saint of Utrecht, in the panel of „The Knights of Christ,“ the banner in his grasp, moreover, charged with the arms of that town: the Counts territory was in the diocese of Utrecht and the ecclesiastical province of Coin. So much depends on the origin of this commission in apportioning the respective share each of the brothers had in its execution that the further fact must not be overlooked that Ghent, for which the great work was completed, had no sort of connection with either Utrecht or Coini being in the diocese of Tournay and the ecclesiastical province of Rheims, while the only saint in the altar-piece specially connected with Ghent who is characterised by an emblem — St. Livin, to wit — was also widely venerated in Zeeland. Finally, not to labour this aspect of the question unduly, the inscription on the frame attributes, not the picture’s inception, but its completion, to Jodoc Vyt, the eventual donor — a form of words so singular as to admit of no other interpretation than the plain meaning the expression conveys.

Count William passed away on the 31st of May 1417, leaving an only child, Jacqueline, aged seventeen, by his wife, Margaret of Burgundy, who had predeceased him. Her uncle, John of Bavaria, Prince-Bishop of Liège, an unscrupulous ruffian who clearly paid small deference to women’s rights, at once set himself to rob the unfortunate princess of her possessions. In September 1418 he marched out on Dordrecht, where he established his headquarters; Gorcum and other strongholds speedily succumbed to his arms, and after an interval, during which he married Elizabeth of Gorlitz, Duchess of Luxemburg and widow of Anthony of Burgundy, Duke of Brabant and Limburg, he finally removed to Holland and installed himself at The Hague, free now to pursue his nefarious projects. For thirteen years the country resounded with the clash of arms and laboured in the rough and tumble of civil warfare: hence an atmosphere the least congenial to the cultivation and patronage of high art. The cities of Flanders and Brabant were the gainers by the exodus of craftsmen that presently set in. Of their number, sooner or later, was Hubert, who, prior to 1425 at any rate, had already settled at Ghent and acquired the freedom of that city. News of the unfinished polyptych remaining on his hands soon came to the ears of Jodoc Vyt, a wealthy burgher, who eagerly embraced the opportunity of striking the bargain by which he acquired all rights in the picture and so linked his name and personality for all time with this ineffable monument of the painter’s art.

In the centre-piece, „The Adoration of the Lamb“ (frontispiece), we discover the keynote to the scheme of the work, in the Apocalyptic Vision of St. John the source of its inspiration. The Lamb without spot, the blood from its breast pouring into a chalice, is stood on an altar, the white cloth over which bears on its superfrontal the text from the Vulgate, „Behold the Lamb of God, who taketh away the sins of the world,” and on its stole-ends the legend, „Jesus, the Way, the Truth, and the Life.” Worshipping angels gather around, some bearing instruments of the Passion, others swinging censers, their smoke laden with the prayers of the saints. In the foreground the Fountain of Life, flowing down through the ages along the gentle slope of flower-bejewelled sward, or dispensing its waters in vivifying jets from the gurgoyles beneath the feet and from the vases in the hands of the winged angel above its standard. To the four quarters groups of the elect: on the near right those of the Old Law and among the Gentiles who had lived in expectation of the Redeemer, the balancing group on the left typical of the New Law — prophets, doctors, philosophers, and princes in the former, the Apostles, popes, bishops, abbots, deacons, monks, and clerics among the latter. The corresponding groups back of the altar represent the army of martyrs whose blood is the seed of the Church, and the multitude of virgins. Over all, from the Holy Dove poised high over the altar, dart rays of light, emblematic of the Wisdom which had inspired their lives and of the fire of Love that had heartened their sacrifice. A carpet of flowers fills in all the open space fore of the altar, flowering shrubs and trees that of the middistance, while the entire background is an exquisite example of the realistic landscape-work that is an abiding charm of the Netherlandish school. The wonderful harmony of colour appeals at once to the senses; but more arresting, on nearer acquaintance, for its quality and felicity, is the wide range of portraiture that distinguishes the piece. From the two lateral panels in the dexter shutter the Knights of Christ and the Just Judges are pressing forward to the scene of the Vision, from the corresponding ones in the sinister shutter the Holy Hermits and the Holy Pilgrims: the former on spirited horses — an animal for whichthe painter evinces a special affection — the latter on foot. These panels are even more remarkable perhaps than the centre-piece for the diversity and multiplicity of the types portrayed, and for the wealth of landscape relieved by bird life lavished in their embellishment

The „Adoration of the Lamb” is dominated in the upper zone by a triple panel, the centre framing the Almighty enthroned in majesty, whose is the kingdom, the power, and the glory — a supreme conception of the Eternal Father, unequalled for majestic stillness of face, intellectual power of brow, and depth and placidity of vision; on His right is the Mother of Christ, testifying to the full the lowliness of the handmaiden of the Lord, on His left St. John the Baptist, an earnest type, long of hair and rugged of beard, barefooted, and in a raiment of brown camel’s hair girdled about the loins, intensifying the austerity of life ordained for him who was to prepare the way of the Lord and make straight His paths. In the „Choir of Angels“ (Plate II.), which is the subject of the first lateral panel in the dexter shutter, we have one of the choicest gems of the polyptych, and it affords us a measure of the distance the realistic tendencies of the painter had carried him from the traditions of the mystic school. Justified by the warrant of Scripture, he translates these spirit beings into purely human frames, but with a nerve system attuned to material sensations. In these angels there is no suggestion of trance-like ecstasy in contemplation of the Beatific Vision; they are angels materialised whose features reflect the strain of sustained effort and the underlying sense of pain which in man is inseparable from the sensing of intense joy. Evidently the master had fathomed the secrets of the human heart: the sense possibilities of the spirit world were without his ken, so he humanised his angels and evolved types understandable of the people, and at the same time one of the finest angel groups of all art. So inexpressibly realistic are his conceptions that to the poet-biographer Van Mander, at any rate, it was actually possible to discern „the different key in which the voice of each is pitched.“ But poets are privileged beings. Accompanying the Choir in their song of praise with organ, harp, and viol are the balancing group of angels in the corresponding compartment of the sinister shutter, types that, strangely enough, are in striking contrast to the former, their features moulded in placid contentment. The extreme panels of this zone are occupied by life-size presentations of our First Parents after the Fall, nude figures painted from the life, with absolute fidelity to nature and masterly conception of type: in a demilunette over the figure of Adam we see Cain and Abel making their offerings unto the Lord, and in that over Eve the slaying of Abel at the hands of his brother. There is a tradition extant that the altar-piece was originally furnished with a predella painted in distemper, a picture probably of Limbo or of Purgatory, but no trace of this remains.

PLATE IV.— PORTRAIT OF THE PAINTER’S FATHER-IN-LAW (By John van Eyck)

The subject of this painting has only within recent months been identified as the father of Margaret van Eyck, with whose portrait, reproduced in Plate VII., it should be compared. The framework bears along the upper border the Painter’s simple motto “Als ich can,“ and at the foot „Johannes de Eyck me fecit anno 1433, 21 Octobris.“ No. 222 in the National Gallery, London. See page 76.

The closed shutters display, filling in the full width of the middle zone, the scene of the Annunciation. The Ethyrean Sibyl and the Cumaean Sibyl occupy the demi-lunettes above the middle portion of the Virgin’s chamber, the lunettes above the lateral divisions showing half-length figures of the Prophets Zacharias and Micheas. Of the four compartments of the lower zone the inner ones contain statues in grisaille of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, the outer ones figures in the attitude of prayer, eminently life-like, of the donor, Jodoc Vyt, and his wife, Elizabeth Borluut. Jodoc was the second son of Sir Nicholas Vyt, Receiver of Flanders, — a wealthy citizen who owned the lordships of Pamele and Leedberghe, besides several mansions in Ghent, of which city he was burgomaster in 1433-34, after filling various minor municipal offices: by no means a handsome type, though manifestly a capable and kindly burgher, well-set, with a somewhat low forehead, small grey eyes, and a large mouth with broad under-lip; neither do the shortcropped hair and growing baldness or the three warts on upper-lip, nose, and forehead make for attractiveness. In respect of looks his wife is the better favoured, striking the beholder as an indulgent lady, with much of the homely dignity and serenity of the finer type of Flemish matron.

The Great Polyptych had not yet reached completion when, on the 18th of September 1426 Hubert van Eyck passed away after a painful illness. How much of the work remained to be accomplished none can tell with any hope of approach to certainty. A whole volume would not suffice for a critical examination of the mass of contending theories that for the best part of a century has been squandered in the endeavour to allocate to the two brothers their respective shares in the execution of the picture. Remember that it had already been some ten years in the making, and that, although it did not receive its final touches from the brush of John van Eyck until 1432, nearly six years after his brother’s death, this period of John’s life, as we shall presently discover, was too fully occupied in the service of Duke Philip of Burgundy to have allowed of his spending any considerable proportion of it in the task of completion. Remembering also that John’s art had been closely modelled on that of his brother, that none better comprehended his ideals or was more intimately acquainted with the working out of his conceptions, mindful, moreover, of the deep veneration in which he held his master’s genius, we must suppose that he realised the obligation of conscientiously adhering to the art and technique of the picture as he found it, any obtruding originality in violation of which would have amounted almost to sacrilege: all this further enhances the difficulty of differentiating between the work of the two painters. Indeed, if so minded, the reader is probably as well equipped as the writer to solve the puzzle.

Hubert van Eyck was laid to rest in the crypt of the chapel for which he had painted his masterpiece, but in 1533, when chapel and crypt had to make way for a new aisle, his remains were transferred to the churchyard, all except the bone of the right fore-arm, which was suspended in an iron casket in the porch of the Cathedral. The brass plate bearing the well-known epitaph was at the same time placed in the transept, only to become the spoil of the Calvinist Iconoclasts in 1578, when already the casket had somehow or other long since disappeared. But what of the painter’s fame, to whose workshop laymen of the highest distinction had felt it a privilege to be admitted, about whose easel journeymen painters had flocked, and whom the leading contemporary artists of the Netherlands had been proud to call master? During his lifetime, and for a considerable period after his death, his was a domi-nating influence in the Art of the North, and Van Mander has it on record that whenever the polyptych was freely exposed to the public gaze crowds flocked to it from morning till night „like flies and bees in summer round a basket of figs and grapes.“ But in the stress and turmoil of succeeding generations his memory gradually faded away; his work, uncared for, lost hold on the imagination; even his great masterwork narrowly escaped destruction. Even so it did not escape dismemberment, or profanation at the hands of the „restorer.“ Saved from the fury of the Iconoclasts in 1566, and subsequently rescued from the Calvinist leaders who contemplated its offer to Queen Elizabeth in acknowledgment of her subsidies, it eventually became the spoil of the French Republicans; but after the battle of Waterloo restitution was effected, and the main portion of the altar-piece, all that remains of it in Ghent, was reinstated in its present position. The Adam and Eve panels, which in 1781 had offended the unsuspected modesty of Joseph II., and in consequence been deferentially removed, were ultimately ceded to the Belgian Government, and now rest in the Royal Gallery at Brussels; while the other six shutter panels, which had been safeguarded through the French occupation, were shamelessly sold to a dealer in 1816 by the Vicar-General and churchwardens — in the absence, it is right to say, of the Bishop — for a paltry 3000 florins, subsequently changing hands for 100,000 francs, and eventually becoming the property of the Prussian Government for four times that amount.

PLATE V.— JOHN ARNOLFINI AND JOAN CENANI, HIS WIFE (By John van Eyck)

An incomparable example of the Master’s varied gifts, and a valuable study of contemporary dress and domestic furniture. Joan Cenani is presumed to have been a younger sister of Margaret van Eyck, with whose portrait, reproduced in Plate VII., it should be compared. The carved frame of the mirror on the far wall enshrines ten small medallions, exquisite miniatures representing the Agony in the Garden, the Betrayal and St. Peter’s Assault on Malchus, Christ led before Pilate, the Scourging at the Pillar, the Carrying of the Cross, Calvary, the Deposition, the Entombment, the Descent into Limbo, and the Resurrection. On the wall above the mirror we read the precise statement, „Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434.“ No. 186 in the National Gallery, London. See page 67.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches VAN EYCK MASTERPIECES

Plate III. Portrait of Tymotheos, 1432 (By John van Eyck.— National Gallery, London, No. 290)

IV. Portrait of the Painters Father-in-law, 1433 (By John van Eyck.— National Gallery, London, No. 222)

V. John Arnolfini and Joan Cenani, his Wife, 1434 (By John van Eyck.— National Gallery, London, No. 186)

alle Kapitel sehen