I. THE ADVENT OF THE VAN EYCKS

THE advent of the Van Eycks is the most important landmark in the history of painting in northern Europe. With them we open an entirely new chapter, for although the value of oil in various inferior processes of the art had been ascertained and availed of at an eariier period, it was entirely due to their long and painstaking experiments that its use was perfected as the vehicle of colouring matter in picture-painting. Unfortunately, time and its worst incidentals have obliterated the evidence which would have enabled us to follow the development of this new method, just as they have robbed us of all the earlier work of its original expounders, leaving us at the same time much too inconsiderable remains for a comprehensive survey of the school of which they were the finished product. It is a disconcerting experience to encounter primarily the lifework of two such eminent painters at a stage when they were already in the plenitude of their powers, and an experience that must always tax the ingenuity of the student and critic of their art. Particularly is this the case in respect of the elder brother, for the ascertained facts of Hubert’s history are restricted to the last two years of his life (1425-26), while of the masterpieces he bequeathed to posterity only one can be said to be absolutely authenticated, though of others generally ascribed to him several may safely be accepted as genuine.

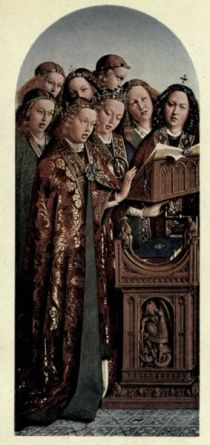

PLATE II.— CHOIR OF ANGELS (By Hubert van Eyck)

The first dexter lateral panel in the upper zone of the interior of the Great Polyptych: now in the Royal Gallery, Berlin. Painted in or before 1426. See page 31.

John’s career, on the other hand, can be traced back to 1424, but the chronology from that date to his death in 1441 is fairly ample, while he has left us a rich heritage of attested paintings to exemplify the varying aspects of his remarkable genius.

It was in the nature of things that the monastic institutions, which in the early Middle Ages were exclusively the nurseries of learning and of the arts and crafts, should have infected these with the mystic spirit induced by the more or less contemplative life its inmates led. More especially must this have been so when we consider that their labours were wholly in the service of religion. As time went on, and monasticism progressed from the pursuit to the dissemination of knowledge, the pupils developed under its influence were naturally imbued with the same spirit, and so a tradition grew up and spread which held undisputed sway for a considerable period in the various centres where artists congregated and formed schools. In the earlier Rhenish school of Cöln this was the dominant note of its art, which it cherished and sustained in all its purity and simplicity to a later period than any of its offshoots and rivals; for as its teaching extended, more particularly northwards, we are conscious of a weakening of its traditions, of a gradual evolution from the spiritual idealism of its mystic brotherhood to the more humanistic realism that is the distinctive feature of Netherlandish art, from the utter sinking of personality to the frank assertion of individuality. Nor does this divergence necessarily bespeak a weakening of religious vitality: rather is it to be ascribed to a marked difference of temperament and race characteristics. Neither could this change have been as abrupt as might appear from the scant remains of the art of the period. It was a natural growth, the one inherent quality of all such developments, ever tending to the elaboration of a higher type, and eventually producing its finest exemplification in the person of Hubert van Eyck. In his younger brother, on the other hand, who almost belonged to another generation, we soon note a more striking falling away from the earlier ideals, and in the event an almost total emancipation from the canons of the mystic school, the explanation of which is probably to be sought in an equally marked difference of character and temperament in the two brothers: the one more poetic and imaginative, the other more objective and materialistic; the one drawing his inspiration from a humble and devout cultivation of art by the light of the sanctuary, the other from a devotion to art for art’s sole sake, involving all the difference that divides the expression of beauty of thought and mere beauty of form, the spiritual and the intellectual: each nevertheless supreme in his own sphere, and wielding an influence and authority destined to leave their impress on all the afterwork of the school.

PLATE II.— CHOIR OF ANGELS (By Hubert van Eyck)

The first dexter lateral panel in the upper zone of the interior of the Great Polyptych: now in the Royal Gallery, Berlin. Painted in or before 1426. See page 31.

John’s career, on the other hand, can be traced back to 1424, but the chronology from that date to his death in 1441 is fairly ample, while he has left us a rich heritage of attested paintings to exemplify the varying aspects of his remarkable genius.

It was in the nature of things that the monastic institutions, which in the early Middle Ages were exclusively the nurseries of learning and of the arts and crafts, should have infected these with the mystic spirit induced by the more or less contemplative life its inmates led. More especially must this have been so when we consider that their labours were wholly in the service of religion. As time went on, and monasticism progressed from the pursuit to the dissemination of knowledge, the pupils developed under its influence were naturally imbued with the same spirit, and so a tradition grew up and spread which held undisputed sway for a considerable period in the various centres where artists congregated and formed schools. In the earlier Rhenish school of Cöln this was the dominant note of its art, which it cherished and sustained in all its purity and simplicity to a later period than any of its offshoots and rivals; for as its teaching extended, more particularly northwards, we are conscious of a weakening of its traditions, of a gradual evolution from the spiritual idealism of its mystic brotherhood to the more humanistic realism that is the distinctive feature of Netherlandish art, from the utter sinking of personality to the frank assertion of individuality. Nor does this divergence necessarily bespeak a weakening of religious vitality: rather is it to be ascribed to a marked difference of temperament and race characteristics. Neither could this change have been as abrupt as might appear from the scant remains of the art of the period. It was a natural growth, the one inherent quality of all such developments, ever tending to the elaboration of a higher type, and eventually producing its finest exemplification in the person of Hubert van Eyck. In his younger brother, on the other hand, who almost belonged to another generation, we soon note a more striking falling away from the earlier ideals, and in the event an almost total emancipation from the canons of the mystic school, the explanation of which is probably to be sought in an equally marked difference of character and temperament in the two brothers: the one more poetic and imaginative, the other more objective and materialistic; the one drawing his inspiration from a humble and devout cultivation of art by the light of the sanctuary, the other from a devotion to art for art’s sole sake, involving all the difference that divides the expression of beauty of thought and mere beauty of form, the spiritual and the intellectual: each nevertheless supreme in his own sphere, and wielding an influence and authority destined to leave their impress on all the afterwork of the school.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches VAN EYCK MASTERPIECES