Port Facilities

The harbor before 1850. Ancient methods of discharging and warehousing. Steamers and their new demands. Construction before 1882. Hamburg enters the Customs Union. The new Free Port. Its commercial advantages. Its manufacturing advantages. Its maritime advantages. The belt canal. New piers of Hamburg-American Line. Pier sheds. Unloading liners. Museum model in Berlin. Use of midstream mooring posts. State piers and leased piers. Handling coal. Area of the harbor. Draying in Hamburg. Lightering. Handling barges. The railroad terminal. German forwarders. Free Port Warehousing Company and the warehousing business. Emigrant village of the Hamburg-American Line. Harbor works in Cuxhaven. Its abandonment except as port of call. Cost of harbor construction. Fiscal policy. Hamburg compared with other ports. Speed of discharge is the essential. Summary.

Chapter III. Port Facilities.

In view of the present widespread agitation for improving the port facilities of our American harbors, the importance of this subject need not be emphasized. Port facihties mean provision for the proper contact between the ocean carrier and the coastwise vessel, between the ocean carrier and the railroad, and between the ocean carrier and inland waterway craft, if there be such. Warehouses, destined to shelter for more or less long periods goods sent through the port, must have proper connection with the inland, ocean and coastwise carriers. If the migrant trade is sought, suitable accommodations for it must be furnished. Local exporting industries attach to the port an inbound and outbound traffic which nothing can take away from it. Other things being equal, that port will distance its competitors which provides the best, cheapest and most expeditious terminal, transshipment, warehousing, emigrant and industrial facihties. As in America channels to the sea are constructed for our ports by the national government, the lesson from Hamburg for our cities must be primarily in the matter of port facilities.

The original Hamburg harbor was on the river Alster, a small stream which flows through the city. As the wall and moat of the city were repeatedly pushed outward, the old moat became a canal, on whose banks the warehouses were erected which served Hamburg’s transshipment trade. The small seaships penetrated the canals and came directly to the warehouses. Not until the seventeenth century, when the Alster and the canals had become overcrowded, did the Elbe itself come into use as a harbor. It became more important when, after 1800, the larger sailing ships were no longer able to enter the canals.

Until 1866 the Hamburg harbor consisted of a stretch of river, with mooring posts driven into the river bed, to which the ships made fast. By human labor and the ship’s tackle, they discharged into small lighters, which were poled or carried by the tide upstream to a hand crane on the bank or into one of the many canals on which the warehouses lay. The canals are not so numerous as they were, but there are still enough of them to make the stranger understand why Hamburg was called the Venice of the North. The warehouse wall rises directly from the water’s edge, so that the lighter can lie close alongside. Above the door of the top story the arm of a hoist projects; it brings goods up from the lighter and they can be pulled in at the door of any floor. The warehouses still occupied — and there are many of them — operate their hoists electrically; they used to be wound up by hand. The canal frontage of the deep narrow building was a warehouse, the street frontage often the merchant’s residence. Some of these canals are little changed and a trip through one in a row boat or a launch at high water — at low water they are almost dry — gives one a strong impression of having dropped in upon the fifteenth century.

When steamships came in, this method of discharging the cargo would no longer suffice. The steamship clamors for punctuality and speed in loading and discharging. Its profits depend on the number of voyages it makes in the year. Cargoes became so huge and various that sorting them on the ship’s deck for distribution into the lighters of numerous warehouses and into river barges was an endless task. To meet this difficulty large lighters were at first employed to act as floating piers. Into these the steamer dumped its burden; the goods were there sorted and then given over to the various small harbor lighters. But experience in English harbors had shown that quay walls with deep foundations, which allowed the ship to lie alongside the land and discharge into freight sheds, considerably hastened and cheapened the discharge of a cargo. Moreover, the rapid extension of railway transportation brought with it the need for direct contact between the ship and the railroad car.

These considerations made Hamburg decide to provide opportunity for its liners to come directly to land. English engineers were called upon to prepare plans for the construction of a modern harbor. In total disregard of the difference in conditions between London or Liverpool and Hamburg, they recommended closed docks with lock gates, like those of the English ports. In spite of the opposition of State Engineer Dalmann, the construction of such a dock was begun, but the superfluity of the entrance lock was seen before the construction was finished and it was never built in. As a result, Hamburg has today a system of open basins cut into the land, leaving solid piers projecting; it has not the English system of closed docks, with their hours of inactivity when ships and barges cannot get into the docks, or, if they are in, cannot get out.

Basins or „harbors“ (Hafen) were cut into the land because the cheaper process, prevalent in America, of building piers out into the water, was not practicable. Hamburg lies eighty-five miles distant from the open sea, up the river Elbe, and the river is here so narrow that the construction of projecting piers would have left insufficient width for a channel. But, for a reason which we shall consider later, most of the basins were made wide enough so that vessels could lie at the quays and discharge into freight sheds, while at the same time other ships tied up at a line of mooring posts, which bisects the basin longitudinally, and discharged into lighters and upcountry barges alongside. The first of these slips or basins, the Sandtorhafen, was opened in 1866. In the seventies the Grasbrookhafen was opened.

In the meanwhile, in 1871, the German Empire had been formed, into which Hamburg and Bremen entered only on condition that they should remain outside the Customs Union, consisting essentially of the members of the Empire. Germany developed rapidly, in an industrial way, and imports and exports for it began to be of greater significance for Hamburg than the old transshipment trade. After the independence of Belgium was attained, in the thirties, Antwerp awoke to a new commercial and maritime greatness, and, by the excellence of its new port facilities and the versatility of its steamship connections, was drawing heavily on the foi’eign trade of West Germany. It was time for the Elbe port to prepare for the needs of modern commerce. Bismarck had long importuned Hamburg to join the Customs Union. In 1882 it consented, ostensibly unwillingly. No doubt a leading ground for its consent was the fear that the exceptional tariffs which the German railways, under the leadership of Prussia, were granting to German seaports, would be withheld from one that persisted in remaining a foreign country.

However, a good bargain with the Empire was made, which retained for Hamburg many of the advantages that it had formerly enjoyed. The state of Hamburg, practically identical with the city of Hamburg, with 275,000 inhabitants, entered the Customs Union. Its harbor proper was to remain outside the Union and was to be rebuilt, isolated from the rest of the city. The Empire agreed to contribute forty million marks towards the construction of this Free Port.*) The remaining costabout one hundred and fifty milKon marks**) — has been borne by Hamburg.

The Sandtorhafen and the Grasbrookhafen had been built into a peninsula on the right— cityward— bank of the main Elbe stream. The whole peninsula, as well as the island of Kehrwieder between it and the city, was preempted for the Free Port. As no one was allowed to live there, 1,000 property owners were expropriated and 24,000 people made homeless.***) In this right-bank peninsula one more huge basin, the Baakenhafen, was constructed; 1,200 acres of marsh land were purchased on the left bank of the river and new basins excavated there. To the Free Port, opened in 1888, many additions have been made, all on the left bank, the last and greatest being the basins on Kuhwarder, built for and leased to the Hamburg-American Line.

*) Of course Hamburg sacrificed something when it came into the Customs Union. Her 900,000 inhabitants now pay the German duties —averaging perhaps 25 per cent— on imports. According to the terms of the agreement with the Empire, Hamburg must pay 1,700 men $1,000,000 a year to guard the Free Port. (Boston Society of Architects, page 24.)

**)Wiedenfeld: Hamburg als Welthafen, page 19.

***)Aftalion, page 505.

The Free Port consists of a large number of basins, lined by quay walls, alongside which steamers can lie and be discharged by cranes into freight sheds, amply supplied with railway connections. In the wide basins, mooring posts provide anchorage for ships handling cargo in the stream. There are warehouses directly on the waterside. Between the various left-bank basins are located shipyards and numerous exporting industries. The whole Free Port, therefore, considered by the customs department as foreign territory, includes land on either bank of the Elbe and the main river itself for a considerable distance. It is surrounded by a customs line, guarded by customs officials. On land the line is designated by high iron palings; along the river it is a floating palisade; where it crosses the river it is an imaginary line guarded at either end by the customs men. At the land and water entrances into the Free Port are provided customs booths, where goods must pay duty when they enter the Empire.

The first advantage of the Free Port is in facilitating re-exportation; indeed, the importance of the re-exportation trade is what, before all else, led to its creation. Merchandise can be brought free of duty into the Free Port, stored in its warehouses, repacked or mixed and then, as conditions of the market dictate, sent across the customs line into Germany or shipped to Scandinavia and the Baltic. In the Free Port foreign merchants can maintain sample or consignment stocks. Bonded warehouses do not offer the same opportunity for unhindered movement of merchandise within a port: everything must be done under the harassing control of customs men. In Hamburg there is no need of counting and verifying pieces when a reexportation is made. A bonded warehouse cannot offer the same facilities for various manipulations necessary to prepare goods for the consumer, such as cutting wines and mixing coffees.*)

The privilege of manufacturing in its Free Port, which Hamburg alone of all German ports possesses, is one that has proved of less benefit than was expected. Its advantage is of course that it allows exporting and outfitting industries to get their foreign raw materials duty free. This advantage has been partly overcome by the system of draw-backs since introduced and applied to manufacturers in the Customs Union: refunding to exporting manufacturers the duty paid on foreign raw materials contained in their manufactured products. The disadvantage under which all industries in the Free Port labor is that, if they wish to sell in Germany, they have to pay on their products crossing the customs line the high duty on manufactured articles, while their inland competitor has had to pay only a low duty on the corresponding raw materials. This disadvantage has become more marked as the home has come to preponderate over the foreign market.

Excepting shipyards, the industries in the Free Port have grown incomparably slower than those elsewhere in Hamburg and are of distinct types.**) They cater to the building, outfitting and provisioning of ships; such are

*) As a Hamburg merchant said, it is not so simple to make Javan from Brazilian coffee, in case of need. (Wiedenfeld: Die Welthafen, page 289.)

**) There are about 15,000 workmen employed in the Free Port, not more than 3,000 outside the shipyards.

shipyards, boiler shops, machine and repair shops and biscuit factories. Or they represent industries principally interested in exporting, such as rice mills and oil mills; or industries settled in the Free Port region before the Free Port was built.*) There has been complaint that manufacturers of inferior and „schwindelhaften“ wares have sought the Free Port out, in order to be free from the severe German official regulations.**)

*) The industries of the Free Port are located across the river from Hamburg. Provision had to be made for feeding the workmen there. This is accomplished by numerous restaurants (Kaffeehallen) under state control. As workmen may not live in the Free Port, there is maintained an elaborate ferry service between various parts of it and the city. In 1909 a tunnel was opened from Hamburg to Steinwarder, in the Free Port, where, among other establishments, the largest Hamburg shipyard, Blohm and Voss, is located.

**)Aftalion, page 195.

Perhaps the chief advantage of the Free Port lies in the facilities it offers for the rapid, frictionless discharging of ships with dutiable goods, whether destined for re-exportation or shipment inland. As Hamburg lies eighty-five miles from the sea, precautions must be taken to prevent goods being landed on the way up. The Hamburg pilot, who must be taken aboard when the vessel enters the Elbe, is sworn in as a customs inspector. Under his guidance the vessel comes up the river at any hour of day or night and passes to her berth in the Free Port, unmolested by customs officers. There are no summary or detailed declarations of dutiable goods to be made, no customs officers to be taken aboard, with the explanations and delays attendant on their presence. Where, as in England, their official hours are limited, a ship with dutiable wares must suspend the discharge of her cargo during night hours. In the Hamburg Free Port, she discharges and loads day and night, if she will. When she is ready, her inspector-pilot takes her out to sea; no officer of the customs has even been aboard. It is the least conceivable hindrance of the free movement of a ship.

There is of course no occasion for vessels engaged in the German coasting trade to enter the Free Port. They discharge on quays on the right bank of the Elbe, outside the Free Port district. Moreover, as the Elbe above and the Elbe below Hamburg are within the Customs Union and as part of the main stream is within the Free Port, barges plying between upper and lower Elbe would have to be examined after coming through the Free Port, if they were obliged to use the main stream for their passage. To obviate this necessity, the right bank peninsula, already mentioned, has been cut to form a belt canal, which acts as a partial boundary between the Free Port and the city, and through which the barge traffic between upper and lower Elbe plies unhindered. However, it is in the Free Port that the main part of Hamburg’s shipping is handled, and its facilities are those that interest us.

There is little essential difference between the various basins of the Free Port. A description of the newest and best, the piers of the Hamburg-American Line, will serve for all. The Hamburg-American piers were constructed by the state of Hamburg in the year 1903, at a cost of thirty-two million marks, and leased to the HamburgAmerican Line at a yearly rental of 1,350,000 marks.*) Three basins have been cut into an ancient meadow, the

*) Richter: Führer, page 63.

Kuhwärder, leaving two huge, solid piers projecting. The piers are lined with concrete quay walls, with foundations so deep that the berths are dredged to a depth of 32.8 feet, the high water depth of the channel. The solid piers are so wide that each carries two rows of sheds, one on either edge, as well as railroad tracks before and behind the sheds. One side of the longer pier has a length of 3,500 feet and carries three enormous pier sheds. In front of these, spanning the water-edge railroad tracks, are numerous electric cranes — one every 100 feet — with a lifting power of two tons each. They have a „halfportal“ form: a vertical leg runs on a rail on the very edge of the quay, a horizontal leg on a rail on the shed, just above the door.*) Cars and locomotives pass beneath the cranes, which are themselves movable longitudinally. Back of the shed, flush with the rear railway tracks, is a street, which may be used to dray goods to Hamburg or to near-by piers. Hand cranes serve to lower heavy pieces from the rear platform into car or dray. For handling freight within the pier shed, the HamburgAmerican Line is experimenting with electric trucks of the three-wheel type, capable of carrying 5,000 pounds each at a speed of four miles per hour. Each does the work of six men with the old hand trucks.

*) It is interesting to observe, in various German harbors, cranes representing successive stages in pier crane development. The earliest form was the stationary hand crane. Then came the stationary steam crane, disadvantageous because the vessel had to be moved to and fro to bring her hatches, one after the other, within reach of the crane. The stationary steam crane was followed by the movable steam crane — it was easier to move the crane than the ship. But the early movable steam crane took up the width of a railroad track on the pier edge, for itself. The next stage was the electric (or hydraulic) portal crane, which put the mechanism out of the way, seated on a portal that ran on rails outside the railroad tracks, which it spanned. The last stage was the half-portal crane, in which the inner leg of the portal is taken out of the way; the horizontal beam of the framework runs on the shed itself. Perhaps the highest stage of pier crane development is reached by the roof cranes at Liverpool. They run on the slanting roof of the pier shed, outside, and do not in any way interfere with the utilization of the space on the pier’s edge beneath.

Before a liner arrives, the import shed where she is to discharge and the export shed where she is to load are ready for her. Freight trains and drays have been unloaded on the front and rear platforms of the export shed, river barges and harbor lighters have lain alongside the quay and had their freight hoisted and swung across the railroad tracks to the shed platform by silent electric cranes. A big river barge — they average 600 to 800 tons capacity — cannot enter the seaship basins unless it has at least fifty tons of freight to exchange with a seaship; otherwise it must send a Httle harbor lighter — they average about sixty tons — to the ship.*) This prevents unnecessarily clogging up the basins with unwieldy river barges. Similarly, the import shed has been emptied for the liner by cars, lighters, drays and barges.

The liner ties up at her import berth. A swarm of pier cranes brings up goods from the hold and swings them across to the shed platform, whence they are trucked inside. There they are counted, sorted and arranged for shipment direct inland by barge or rail, or for sending by lighter or dray to warehouse or railroad station (lessthan-carload lots). If freight needs no sorting, it may be dropped by the crane into a freight car standing underneath. Similarly, goods destined per barge for points on the upper Elbe, on through bills of lading, may be dropped by the ship’s tackle overside directly into the barge.

*) Recently there is talk of increasing to 100 tons this minimum that a barge must have for a seaship in order to be allowed to approach it. Surely such regulation will be necessary for the harbor of New York, when the Barge Canal is finished and the Barge Canal Terminal is constructed in New York.

In the Berlin Museum für Meereskunde (Marine Museum) is a model of one end of a basin of the HamburgAmerican Line, on Kuhwärder. The „Patricia“ and the „Blücher,“ in the New York service, lie at the Auguste Victoria quay, before shed 73, which is about 1,300 feet long and 200 feet deep. Half of the building is serving as import, half as export shed. The „Blücher“ has nearly completed her cargo and the shed behind her is almost empty. On her water side a great floating crane has brought and is lowering into a hatch huge steel beams for bridge construction work, too heavy for the pier cranes or the ship’s derricks to handle. The ship’s derrick is raising from a lighter, which has hastened up, an express consignment that nearly missed the boat. A fresh water boat has come alongside and is charging the ship’s fresh water tanks. On the land side a line of coal cars stands on the quay’s edge. Boards have been laid from the cars to chutes into the ship’s bunkers, and over these boards men are walking with baskets, coaling the vessel.

The „Patricia“ is discharging. Here cranes are in full activity, swinging cargo from the ship’s hold across to the shed platform, there to be trucked inside. A part of the roof of the model has been removed and through the opening one sees merchandise in the shed being sorted. Already they are loading into freight cars from the rear platform of the shed, and into drays which will take the goods to Hamburg, On the water side of the vessel, the ship’s tackle is lowering freight into lighters. Among them lies a grain discharger, opposite a portion of the ship filled with grain; it lies between the ship and an 800ton Elbe barge. The discharger lets its long proboscis down into the hold, sucks out the grain, cleans and weighs it and slides it into the capacious hatches of the river craft.*) A remarkable expedition of discharge is attained by the use of all this freight-handling machinery, particularly the pier cranes. A ship like the „Patricia,“ which, besides a long passenger list, carries a cargo of 10,000 tons, is unloaded in about forty hours and loaded in thirty to forty more.**) This is at the rate of 250 tons of cargo per hour and is the regular rate of discharge at the Kuhwärder piers. On December 9, 1910, the „Saxonia“ of the Cunard Line created a new speed record for handling cargo in Boston. She loaded 4,500 tons in twentysix hours, a speed of 175 tons per hour.***)

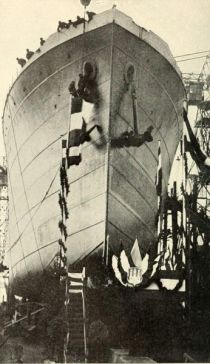

At the Reiher quay, the repair berth across the end of the Kuhwärder basin in the model, lies the pleasure yacht „Prinzessin Victoria Luise,“ since lost. That she is being repaired is indicated by the scaffoldings of scrapers and painters on her hull and funnels. The big twenty-ton hammer-shaped crane on the quay is lowering into her a boiler; next the crane lie heavy pieces of machinery, awaiting their turn. At the vessel’s prow a hghter is testing the anchor chain, link by link.

*) For discharging loose grain in Hamburg, there are ten floating pneumatic elevators, which are capable of discharging 700 to 800 tons per elevator per day, out of one hatch. Thus four of them working on a ship discharge 3,000 tons per day.

**)Stahlberg, page 30.

***) See Boston papers of December 10.

It has been observed that the mooring posts of early days have been retained in the new basins. The basin in the model is wide enough to accommodate a line of vessels at either quay and a line on either side of the double row of mooring posts that runs down the center of the basin. In the model, the „Rhenania“ and „Abyssinia“ are tied up at the mooring posts. They are loading with their own tackle from a horde of lighters and barges that surround them, bringing cargo from the railways and from up-river. Perhaps there is no room for them at the quay. Perhaps they are not in line service, but are engaged in taking a casual cargo of bulk goods of low specific value, such as potash or raw sugar. In the case of state piers, wharfage dues are purposely put so high that they discourage the use of piers by tramp steamers with bulk cargo. In the case of the „Rhenania“ and „Abyssinia,“ the Hamburg-American Line apparently thinks that their cargo is not of sufficient value and does not require such expedition in loading as to justify them in taking up room at the piers. In general, the liners, carrying package freight, which demands expedition, discharge and load at the piers.*) The vessels in casual or tramp service, whose cargoes, as a rule, consist of bulk goods, handle their freight in midstream. It is of course possible to discharge a cargo of package freight at the piers and go to the mooring posts to take on a bulk

*) An addition to the pier dues of a steamer, after she has been at a state pier for five days, causes all the larger steamers which dock there to go to midstream to load. They cannot discharge and load in five days, and the additional dues are too heavy for them to stand. The lines which lease piers have both discharging and loading of their liners done at the piers.

cargo. In any case, the midstream mooring posts mean a doubling of the port’s capacity.*) Nearly half the tonnage of vessels entering Hamburg discharge in midstream, as is indicated by the following table:

Vessels Using Piers and Mooring Posts to Discharge, Hamburg, 1907.**)

...........................................................................................Average

...........................................................................................Tonnage

.................................................Vessels.......Reg. Tons .........per Ship

State Piers,..................................5,023.........3,903,000.............777

Leased Piers,.................................736..........2,389,000 3,246

All Piers,.....................................5,759.........6,292,000..........1,093

Discharged at Mooring Posts,...10,714........5,748,400.............536

Ten thousand seven hundred and fourteen vessels of 5,748,000 register tons did not use the piers to discharge. The difference between the average size of ships discharging at the state and at the leased piers will be noted. Lines to England, Scandinavia, etc., are berthed at the state piers; their steamers run from 500 to 1,000 tons. The great oversea companies with large steamers — such as the HamburgAmerican Line, the Gennan East African Line and the Woermann Line — lease their piers. In general, state ownership prevails in the older, right-bank basins, whose shallower depth suffices to accommodate the smaller European liners. Leased piers predominate in the newer, deeper basins on the left bank, and in the right-bank Baakenhafen. At the state piers, vessels are accommodated in turn, preference being given, however, to steamers over sailing ships, and to steamers of regular lines over irregular visitors.

*)When the berths are crowded, even steamers with general cargo must often discharge at the mooring posts. The operation is slower there than at the quay, owing to the necessity of assorting packages on the ship’s deck, according to marks and numbers, and owing to the necessity of constantly shifting lighters.

**) Statistik der Kaiverwaltung. Hamburg, 1907.

English coal (four and one half million tons in 1907) is discharged in the new coal „Hafen,“ below the Kuhwärder basins. Discharge is by tackle and basket. There is a separate Petroleumhafen, whose entrance can be closed by an iron pontoon, which prevents burning petroleum from flowing out into the main harbor; the pontoon is kept so closed at night. The shores of this basin are lined with tanks, into which oil is pumped from the tank steamers of the Deutsch-Amerikanische Petroleum Aktien-Gesellschaft, or as it is abbreviated, „Dapag,“ the German daughter of Standard Oil. One of its steamers, the „Niagara,“ carries 10,000 tons of oil.

There are strangely few grain elevator buildings at the water’s edge, scooping their grain out of ships; but, as we shall see, the grain trade and grain storage have moved inland. At the coal quay, coal tips grasp a car and tip it until its contents flow into a ship. The tip is used principally in loading coal for export, and for coaling tramps, which are little disturbed by the dirt occasioned by having their bunker coal dropped into them from a height of several yards and which do not mind the loss of time in going to and from the coal quay. Liners, which usually carry passengers and cleanly freight, cannot stand the dirt or lose the time. While lying at their berths, loading, they are coaled from lighters on the water side or coal cars on the land side. There has been recently constructed in the Free Port a great potash elevator, somewhat on the principle of the American grain elevator building. Its bucket-chain brings the potash up from Elbe barges. It is stored and later slid into ships for export.

The entire Hamburg harbor consists of eighteen such basins or „harbors“ as those of the Hamburg-American Line, already described. The depth of these basins varies from five and one half meters (eighteen feet) in the Sandtorhafen, the oldest, to ten meters (32.8 feet) in the new Kuhwarder basins. There are also numerous basins of the harbor, yet to be described, devoted to its river barges, and having depths of four to six feet and more. The water surface of the harbor has grown from 61 acres in 1854 to 1,576 acres in 1909.*) This acreage was used as follows:

Water Area of Hamburg Harbor.

Basins for seaships,........................................... 723 acres

Basins for river barges,...................................... 375 acres

Canals and branches with seaship depth,............103 acres

Canals and branches with barge depth................. 36 acres

Main stream and entrance to basins,................... 338 acres

Total,.................................................................1,576 acres

The entire length of water front is forty-one miles. Of this total, twenty-one and one half miles border on water with a depth for seaships, nineteen and one half miles on water with a depth for river barges. Of this total water front of forty-one miles, thirteen and three fourths miles have been supplied with perpendicular quay walls with deep foundations, which allow ship or barge to come alongside, within reach of the cranes.

*) These statistics are from: Hamburg als Schiffahrts- und Industrieplatz, I. Beiblatt, Hamburg, 1910. In addition to the water space detailed above, there are fifty-four acres of protected water area in Cuxhaven. The total area of the Free Port, including the land therein, is 2,508 acres. (Barge Canal, I., 412.)

The combined length of the harbor pier sheds is eight and one half miles, their total floor space five million square feet. There are 808 cranes in the harbor, with a combined lifting power of two million tons. The largest cranes lift 150, 75 and 50 tons, respectively. The length of railroad tracks in the harbor is 138 miles — ^by way of comparison, the distance from Hamburg to Berlin is 189 miles.

There are four lines of transportation engaged in collecting and distributing the freight carried by the seaship: dray, lighter, barge and railroad car. The following table illustrates the part played by each of these vehicles in disposing of goods discharged at the piers in Hamburg:

Removal of Goods Discharged at Hamburg Piers, 1907.*)

By...........................Per Cent

Rail............................18

Dray, ........................ 20

Lighter, .................... 45

That leaves 17 per cent removed by barges, whose cargo, however, is procured mainly from vessels in midstream.

Drays are used primarily to carry goods between the piers and the city of Hamburg, such as goods for local consumption. The local consumption of a city of 900,000 inhabitants is a very considerable item. Horse and wagon also take merchandise from warehouse to the freight-receiving station of the railroad. In winter, when ice in the harbor makes lightering dangerous, drays are called on to transport goods between piers, as in the transshipment trade, or between pier shed and Free Port warehouse.

*) Report of the Metropolitan Improvements Commission, page 185. Boston, 1910.

There are in the harbor of Hamburg 500 covered and 2,500 uncovered lighters, 3,000 in all,*) with a carrying capacity of 20 to 250 tons each. As already set forth, they were formerly carried by the tide from ships anchored in midstream, which had given them their goods, to warehouses lying on the old city canals, and vice versa. They were guided and helped along by their steersmen, supplied with long poles with hooks in the end. The pole could be put into the river and pushed on, or hooked to an anchored vessel or anything else solid, and the lighter thus pulled forward. This method of procedure was borrowed from London, where it may still be observed in full bloom. In London, the custom of towing lighters is just coming in, principally for tows of coal upstream. But Hamburg has no potent guild of Watermen and Lightermen who have prevented lightering from emerging from its mediaeval form of organization. The Hamburg lighters are towed about. The stream is not cluttered up with struggling, swearing lightermen, drifting helplessly with the tide, in the way of each other and of everyone else. There are numerous Hamburg lighterage companies, and this business is also a branch of the large inland transportation concerns, notably the United Elbe Navigation Company.

*) Barge Canal Terminal Commission, I., 411.

Lighters are engaged in transferring goods between pier shed and warehouse — practically all warehouses, in the Free Port and in the city, are on the water’s edge; between pier shed and pier shed or ship and ship, in the transshipment trade; between pier shed or midstream ship and the waterside freight-assemblage station of the railroad, soon to be described. Finally, the lighters mediate between barges and seaships which have less than fifty tons of cargo to exchange with each other, in which case the barge is not allowed to approach the ship.

Elbe barges handle over half the freight that Hamburg sends inland or receives from there. They are primarily engaged in carrying bulk goods — coal, grain, potash, raw sugar — which they interchange usually with vessels moored in midstream. However, they handle a very large amount of freight in interchange with the ships at the quays. If their liner is at her berth, they can lie alongside and interchange cargo over the ship’s side. If she is not at her berth yet, or has left, they lie at the quay and have their freight discharged or loaded by pier cranes. The nature of the barge terminal facilities at Hamburg is more fully described in a later chapter.

Finally, the railroads. The harbor tracks are owned by Hamburg but operated by the Prussian state railways, which form Hamburg’s connection with Germany, as part of the Prussian system. Delivery to the port of Hamburg means delivery to any pier; there is a terminal charge of one mark (23.8 cents) per ton, reduced on certain low grade goods discharged direct between car and ship at quays especially fitted up for this form of transfer — supplied with cranes but no pier sheds. However, this traffic is inconsiderable;*) by far the larger part of the freight arriving by sea, and discharged at the quays, is sorted at the pier sheds before shipment inland. If rail shipments are in carload lots, they are sent direct from the shed platform. If they are in less-than-carload lots, they are put on lighter or dray — on lighter, if they come from one of the new, distant piers — and sent to the assemblage freight-receiving station of the railroad.

*) It varies from 100,000 to 150,000 tons of goods per year in all, and consists primarily of Chili saltpetre received, and coal shipped. (Stahlberg, page 26.)

There is a large difference in the railroad tariffs on package freight in carload and less-than-carload lots, respectively. So in Germany an important role is played by the forwarders, who assemble L. C. L. shipments and send them off by the carload. Part of the saving in freight rate, which they effect, is of course allowed to the shipper. These forwarders are allowed space in the assemblage freight-receiving station, located near the Free Port warehouses, on the water’s edge, so that it is accessible to dray or lighter. Each forwarder sends so often per week a carload or more of this freight to Berlin, one to Dresden, to Munich, etc. Each steamship company and warehousing concern has its forwarder. The counterpart of the railroad assemblage freight-receiving station, where forwarders send in carload lots combinations of L. C. L. shipments, is a freight-delivery station, similarly situated. Here the forwarders receive in carloads assembled shipments from their agents from different points in Germany and near-by foreign countries. The separate shipments are sorted out and drayed or lightered to their destinations all over the harbor.*)

*) Transit cars from Austria, Switzerland, etc., with goods destined for export via Hamburg, are sealed when they cross the German border. Their seals are simply removed when they enter the Free Port. If a car has assembled L. C. L. shipments, for export, it goes to the assemblage delivery station of the railroad and has its packages sorted out and delivered, all without customs oversight or interference. No bonded warehouse can offer such facilities.

The important warehousing business of the Free Port is in the hands of a privately operated, partly state owned and state controlled concern, the Free Port Warehousing Company (Freihafen-Lagerhausgesellschaft).*) Before 1885 Hamburg’s warehouses lay on the various city canals. When the city proper became part of the Customs Union, the old warehouses became simply bonded warehouses and there was need for the erection of the freer type of warehouse in the Free Port. Hamburg decided that these should be under state control. The North German Bank of Hamburg was authorized to establish a storage concern, the Free Port Warehousing Company, under terms agreed upon by the financial department of the city. The first buildings were erected in the Free Port upon public land, the Kehrwieder island. They still stand, a handsome row of red sandstone structures, facing the city and looking more like a row of university building than like warehouses.

The company was empowered to issue warrants, transferable to order, on goods stored on the property. The stock capital was fixed at nine million marks**) ($2,142,000); tariffs for storage, handling and manipulating goods were fixed in the contract between city and company. Hamburg put 322,930 square feet of land at the disposal of the company and undertook to build the necessary quay walls and slips, in return for a share in the profits. From 1889 to 1905 Hamburg received 3 1/2

*) There is a fairly detailed report on Free Port warehouses in the Barge Canal Commission’s Report, I., 412-416.

**) 1889-1905, dividends were 5 per cent; since then, 5y, per cent.

per cent — since 1905, 5/2 per cent — on a capital of fifteen million marks, representing the value of the land, quays and slips which it furnished. In addition, a portion of the net profits each year is set aside to create a fund for acquisition of the company’s stock by the state, which will eventually be full owner.

The few original warehouses did not long suffice. Sixteen million marks of bonds have been issued to build new ones. By January 1, 1911, 1,161,170 square feet of ground were covered by warehouse buildings, affording 5,417,725 square feet of storage space. Three fifths of this space is leased by the company to particular firms; the remainder is operated by the company in its capacity as a storage concern.

The warehouses are built in double rows, between which a lighter canal runs. Lighters lie alongside and have their merchandise hoisted direct to the floor of the warehouse to which it is destined. Re-exported goods are similarly transferred by lighter from warehouse to seaship. No duty is paid until goods cross the customs line into Germany. Warehoused goods destined inland by barge are lightered to the freight shed of an Elbe navigation company. If destined inland by rail in carload lots, they are shipped direct from the warehouse door;*) less-than-carload lots are drayed to the near-by assemblage freight-receiving station of the railroad. If destined for Hamburg for local consumption, goods are drayed across the bridge over the Zoll Canal, which

*) The older warehouses have no direct rail connection. This is comparatively unimportant; most inland shipments of warehoused goods are in less-than-carload lots and must be drayed to the railroad freight station.

separates the Kehrwieder from the business heart of the city. The largest and finest warehouse, the Kaiserspeicher, has not only rail connection but also a depth of water alongside such that ships can come and be discharged direct into the warehouse: there is no lightering necessary.

The storage business of the company developed slowly. The great importers were loath to leave off their custom of employing their own little warehousing concerns on the canals, who had become expert in performing the necessary manipulations for them and in making their shipments. But the greater freedom of the Free Port warehouses as compared with the — now — bonded warehouses in town; the offer of the company to lease to the merchants space in the new warehouses, where their old agents could still carry out orders for them; the convenience which the company’s warrants afforded as security for loans, etc.; the greater safety and hence lower insurance premiums on goods in the new buildings;*) all this finally attracted the warehousing business to the Free Port.

Growth of Storage Business of the Free Port Warehousing Company.**)

..................................I.........................II....................III.

.............................Packages............Bags of..............Recipts for year.

..................................in...................Coffee......................Storage

..............................Storage.........(included in I.)............Department

End of 1889, .......345,624..............147,137 ...............619,980 Marks

End of 1898,........835,116..............603,012 ............1,115,150 Marks

End of 1908,.....1,927,617...........1,761,847.............2,401,610 Marks

*) The company takes out a general insurance policy on its warehouses and goods stored therein. In consideration of average monthly premiums, it places these policies at the disposal of the merchants. (Barge Canal, I., 414.)

**) Barge Canal, I., 414. At the end of January, 1910, the coffee on hand amounted to 2,236,306 bags.

Particularly worthy of attention is the emigrant village erected by the Hamburg-American Line on land furnished free by the Hamburg government. We shall later see the significance of the Hamburg emigrant trade in furnishing the ships bound for America with a human return freight.

The emigrant village lies on the left bank of the Elbe, opposite Hamburg and completely segregated from the city. This was done in order to protect Hamburg from contagious diseases. The need of such protection became particularly apparent after the cholera epidemic of 1892 and after the majority of the emigrants had come to consist no longer of Germans but of Russians and Austro-Hungarians. A secondary aim of the village is to protect its sojourners from extortion at the hands of the Hamburg merchants.

The village was built in 1900-01 at the cost of three million marks. It consists of about twenty-five buildings, accommodating five thousand persons and is designed to receive only the emigrants arriving from countries where the standard of health is low. At a nominal charge these emigrants are here sheltered from the time of their arrival until the departure of their ship.*) They have already been examined, on entering Germany. Those diseased and those whose physical, moral or financial status promises their rejection at the hands of the American immigration officials, are rejected before they cross the German border, lest they later fall a burden to the German steamship company which would have to bring them back from America. In solid trains those who pass the border inspection are brought to the emigrant village and there re-examined, to eliminate any cases which have been overlooked or which have developed on the journey.

*) Twenty-five per cent of the emigrants pay nothing. The others pay from fifty pfennigs to one mark per day, each.

The emigrants are received in a huge inspection building, where the few suspicious cases are weeded out and sent to the „observation pavilion“ across the road. Most of the arrivals are at once passed to the pavilion where they are to live, though some must first bathe and have their clothes disinfected. A feature of the emigrant village is the simple hotel, where for a slightly higher price the better class of emigrants can have hotel accommodations.*) Each pavilion consists of a dormitory, a large living room, baths, etc. Nationalities are carefully kept separate. There is one large dining hall, with a section set aside for the Jews. The Jews also have their separate kitchen whose methods are supervised by an appointee of the chief rabbi of Hamburg. The village contains a synagogue, a Catholic and a Protestant church. German emigrants are, in general, not received in the village; they must stop in the licensed boarding houses in Hamburg.

The careful surveillance exercised over these boarding houses, and over merchants and others who are tempted to swindle emigrants, the Imperial inspectors who scrupulously inspect the emigrant ships and, above all, the excellent accommodations which the Hamburg-American Line offers foreigners in its village — all these factors conspire to make Hamburg a very popular point of departure for the European emigrant. The degree of

*) Similar to this is the creation of a third-class passage on the boats of the Hamburg-American Line, with accommodations between those of the second class and the steerage.

that popularity is expressed in the high percentage which the Hamburg-American Line gets of the proceeds of the transatlantic emigrant pool, in whose hands the emigrant trade lies. Many an emigrant departs with regret from the village, just as many of them prefer a slow boat to a fast one because the slow boat prolongs a steerage passage where they enjoy a scale of living such as they never knew before.

Finally, there are the harbor works at Cuxhaven, at the mouth of the Elbe, eighty-five miles below Hamburg. Cuxhaven was acquired by Hamburg in the fourteenth century.*) The situation commanded the entrance to the Elbe, on which Hamburg’s life depended. Moreover, Cuxhaven was an excellent harbor of refuge, to which vessels could run in from the stormy North Sea. At the end of the nineteenth century it began to look as if it would be impossible to dredge the Elbe deep enough for modem liners to continue to come up to Hamburg; already they were having to lighter a considerable portion of their cargoes before proceeding up the river. There were already two basins at Cuxhaven; in 1895 a third was constructed. The Hamburg-American Line, owner of the largest ships plying to Hamburg, asked the state to construct and lease to it a quay of this basin with pier shed, cranes, etc., and with a large railway station and customs office. The intention seemed to be to transfer to Cuxhaven the freight and passenger terminus of the big liners engaged in the New York trade.

*) In 1246, half of the island of Neuwerk had been given to Hamburg by the Bishop of Bremen, on condition of the erection of a lighthouse thereon. Later, acquisition was made of the rest of the island, on which a Hamburg deputy, the Ratsherr, lived and watched for pirates and shipwrecks. Opposite the island, the disagreeable lords of Ritzebüttel lived in a castle, supporting themselves and their retainers by the pursuit of piracy. In 1393 the Hamburgers made an expedition against the robber lords and captured the castle. To forestall possible reprisals, Ritzebüttel and the neighboring land were bought from the robbers. From the castle of Ritzebüttel, piracy was now as zealously suppressed as it was formerly practiced. A small refuge harbor was built and pilots were here taken aboard. When the course of the Elbe shifted and left Ritzebüttel high and dry, „Kuckshafen“ was built near by, on the new bank of the stream. There was for centuries difficulty in keeping it from shifting away from Cuxhaven. ( Buchheister, pages 173 seq.)

These constructions were carried out and leased to the HamburgAmerican Line in 1902 for twenty-five years at a yearly rental of 111,000 marks. While the construction work was going on, the steamship company acquired land in Cuxhaven, and began to erect houses for the captains and other ship’s officers, foremen, clerks and workmen who would in the future be attached to the new terminal.

There is a ten-foot difference between high and low tide at Cuxhaven, and soon after the new basin, with its great depth, was opened, it was found that it exhibited a strong tendency to fill up with mud. Moreover, it was found to be dangerous to enter or leave this open basin except at high or low water because of the violence of the tidal flow at other times. A storm in November, 1903, tore the „Deutschland“ from her berth at the quay and inflicted severe damage on her; which demonstrated that there was here too little protection for loading and unloading at a pier shed. At the same time it was becoming apparent that the Elbe could, after all, be dredged for ships of the deepest draught. So the Hamburg-American Line abandoned the use of all parts of the harbor excepting the railway station. Incoming passengers are put off the liners at Cuxhaven and get inland by train several hours earlier than if they had steamed up the river. Mails are of course put off with the passengers. The same time is saved by outgoing passengers and mails, which are not put aboard until the liner reaches Cuxhaven. In good weather the ship comes alongside the river quay, near the railroad station, but outside the basin; in bad weather passengers and mails are transferred by lighter.

The cost of constructing the harbor, including the harbor works at Cuxhaven (nine and one half million marks), but not including dredging the channel nor erecting the Free Port warehouses, has amounted, to date, to about four hundred million marks.*) In return for this expenditure Hamburg does not receive much in the way of direct dues. According to the budget for 1906, as presented to the Senate, there was expected the following income from the harbor:**)

Income of Hamburg Harbor, 1906.

Total,.................................4,861,000 Marks

*) Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reiches, Teil IV., and Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen, Teil VI. In 1909, forty-five million marks more were voted, to carry out extensions. Below the Kuhwärder harbor four new basins will be built: two for seaships, each 300 meters (984 feet) wide; one for seaships, 210 meters (689 feet) wide. Separated from these will be a new Petroleumhafen, 140 meters (460 feet) wide. The present chain of barge basins, behind the left-bank seaship basins and connecting with them, will be continued to serve the new extensions. Between this chain of barge basins and one of the new seaship basins, there will be room for a new shipbuilding yard. (Barge Canal, I., 415.)

**) Richter, page 28.

Principal items.

Dues from state piers, ..................2,757,000 Marks

Rentals from leased piers,.............1,903,000 Marks

The two principal items are thus seen to be: dues collected for the use of state piers, and rentals from leased piers. The third item would be harbormaster’s dues, collected from vessels using the mooring posts, and levied according to their draught. These dues are purposely low, to encourage vessels with bulk cargoes to discharge in midstream instead of at the crowded piers.

The quay dues on cargo discharged at state piers are one mark per metric ton. Ships discharging part of their cargo on the pier and part overside, need pay cargo dues only on the tonnage actually going over the quay. These dues entitle the ship to the use of the pier, pier shed, cranes and cranemen, and storage in the pier shed for two days. Stevedores to discharge the cargo must be found by the ships. In addition to these cargo dues, the vessel must pay seventeen and one half pfennigs per net cubic meter (11.8 cents per net register ton) for the first five days at the berth; three and one half pfennigs per net cubic meter (2.36 cents per net register ton) for each succeeding day, excluding holidays and Sundays.

Ships discharging at the mooring posts pay only the harbormaster’s dues of five marks ($1.19) when of not over two meters (6.56 feet) draught, and five marks for each additional meter. Thus the largest ship that could get up the Elbe would have to pay only forty-five marks dues for discharging in midstream. It is an insignificant item; the cheapness of discharge at the mooring posts is a great boon to vessels with bulk cargo. Other dues are for pilotage (one pilot to Brunsbüttel, one thence to Hamburg), perhaps sanitary dues, etc.

The following are the major items of expense accruing to a vessel of 3,100 tons gross, 2,000 tons net, loaded full with a cargo of dead weight, and departing in ballast:

Charges Accruing to a Vessel Discharging in Hamburg.*)

Total,...............................................1,769 Marks = $421.18

principal items.

Admiralty pilotage,..............................244 Marks

Pilotage from Brunsbüttel,.....................81 Marks

Tonnage dues, .....................................679 Marks

Harbor towage, in and out...................257 Marks

Pilotage outwards................................123 Marks

„To attendance to ship’s business,“.....215 Marks

Stevedore’s charges for unloading the cargo are not included in the above total, though harbormaster’s dues are. The reputable stevedores in Hamburg have combined and have identical charges. For instance, the charge for unloading „Bombay cargoes“ in midstream is 70 pfennigs per ton. Assuming that our ship had 3,600 tons of such cargo aboard, it would cost 2,520 marks ($510) to discharge her. The total cost to her of entering and discharging her cargo in midstream would be $421.18+$510=$931.18.

The stevedore’s charge for unloading Bombay cargoes at the pier is 45 pfennigs per ton.**) If the vessel discharges there, she pays 3,600 marks ($857.14) of cargo dues, and 1,091.20 marks ($236) dues levied according to the ship’s net cubic measurement. The total

*) Barge Canal, I., 400.

**) Less than for discharge in midstream; cranes are supplied with the pier.

cost to her of entering and discharging her cargo at the pier is $421.18=*)+$857.14+$236=$1,514.32. It is apparent why bulk cargoes, of low specific value, are handled in midstream.

In the 1902 Report of the Royal Commission on the Port of London, Sir Alfred Jones, chairman of the board of directors of Elder, Dempster & Company, gave the following comparison of the costs accruing in various European ports to a freight steamer of 5,146 net register tons, with a cargo of 5,000 tons of grain, 3,000 tons of package freight and 2,000 tons of wood:

Dues in Various Euhopean Ports.

...........................Liver-...Ham-...Rotter-...Antw-...Bremer-...Lon-

............................pool......burg.....dam........werp....haven.......don

Harbor dues, ......£404 £411 £136.......£228....£347........£368

Unloading costs,...522.......442.......310.........404......385..........592

............................£926.....£853.....£446.......£633....£732........£960

But such a comparison has a doubtful value. The relative dearness of a harbor is determined not only by these items but also by consulate dues, the cost of lightering the shipment in the harbor from ship to river barge or of switching it over the harbor belt railway to its point of departure inland, etc. To compare the ports on this scale is not possible. Jones says: „The conditions affecting the various ports are so different that a useful comparison is almost impossible.“ Sir Thomas Sutherland, chairman of the Peninsular and Oriental, made little of the height of the dues and said: „Rapid discharge is the most vital of all questions.“ Jones compressed a volume of criticism of London in the sentence: „While London

*) Minus the small harbormaster’s dues contained in this total.

costs about the same as Liverpool or Avonmouth, the despatch is about five times as bad in the case of a large vessel in London.“*) Despatch is life to the ocean liners. The port of London, with the seven and one half million inhabitants of the great city as its assured dependents, may be able to afford not to keep pace with its rivals; certainly no other port can. In this regard, despatch, Hamburg enjoys an enviable reputation. It has been seen that the „Patricia,“ with 10,000 tons cargo, is unloaded in forty hours, loaded in forty more, a feat which probably no other port can equal.

*) Report of the Commission, page 26.

Hamburg, then, has supplied itself with the most modern harbor facilities: provision for the rapid transfer of freight between the ocean, river and rail carriers. Direct contact between the carriers is secured; there is no unprofitable and dilatory juggling of the freight necessary in order to get it from one to the other. The Free Port lets the Hamburg merchants store their goods duty-free and offers them complete freedom of manipulation and the desired option of re-exporting them or of sending them inland, as the market dictates. A still more important advantage of the Free Port today, is that it allows ships in the foreign trade to discharge with the utmost freedom and expedition, without customs officials causing them the least harassment or delay. Industries in the Free Port labor under a positive disadvantage, excepting those directly catering to ships and those more interested in foreign than home markets.

Proper provision has been made for the various special functions which the port has to perform: warehouses, the emigrant village, the port of call at Cuxhaven, the petroleum harbor, etc. The entire port is operated on a financial plan less calculated to make it a profitable investment than to bring prosperity to the city. As compared with other great European ports, Hamburg’s dues are not high; in respect of that vital need, despatch, none stands higher.

Chapter III. Port Facilities.

In view of the present widespread agitation for improving the port facilities of our American harbors, the importance of this subject need not be emphasized. Port facihties mean provision for the proper contact between the ocean carrier and the coastwise vessel, between the ocean carrier and the railroad, and between the ocean carrier and inland waterway craft, if there be such. Warehouses, destined to shelter for more or less long periods goods sent through the port, must have proper connection with the inland, ocean and coastwise carriers. If the migrant trade is sought, suitable accommodations for it must be furnished. Local exporting industries attach to the port an inbound and outbound traffic which nothing can take away from it. Other things being equal, that port will distance its competitors which provides the best, cheapest and most expeditious terminal, transshipment, warehousing, emigrant and industrial facihties. As in America channels to the sea are constructed for our ports by the national government, the lesson from Hamburg for our cities must be primarily in the matter of port facilities.

The original Hamburg harbor was on the river Alster, a small stream which flows through the city. As the wall and moat of the city were repeatedly pushed outward, the old moat became a canal, on whose banks the warehouses were erected which served Hamburg’s transshipment trade. The small seaships penetrated the canals and came directly to the warehouses. Not until the seventeenth century, when the Alster and the canals had become overcrowded, did the Elbe itself come into use as a harbor. It became more important when, after 1800, the larger sailing ships were no longer able to enter the canals.

Until 1866 the Hamburg harbor consisted of a stretch of river, with mooring posts driven into the river bed, to which the ships made fast. By human labor and the ship’s tackle, they discharged into small lighters, which were poled or carried by the tide upstream to a hand crane on the bank or into one of the many canals on which the warehouses lay. The canals are not so numerous as they were, but there are still enough of them to make the stranger understand why Hamburg was called the Venice of the North. The warehouse wall rises directly from the water’s edge, so that the lighter can lie close alongside. Above the door of the top story the arm of a hoist projects; it brings goods up from the lighter and they can be pulled in at the door of any floor. The warehouses still occupied — and there are many of them — operate their hoists electrically; they used to be wound up by hand. The canal frontage of the deep narrow building was a warehouse, the street frontage often the merchant’s residence. Some of these canals are little changed and a trip through one in a row boat or a launch at high water — at low water they are almost dry — gives one a strong impression of having dropped in upon the fifteenth century.

When steamships came in, this method of discharging the cargo would no longer suffice. The steamship clamors for punctuality and speed in loading and discharging. Its profits depend on the number of voyages it makes in the year. Cargoes became so huge and various that sorting them on the ship’s deck for distribution into the lighters of numerous warehouses and into river barges was an endless task. To meet this difficulty large lighters were at first employed to act as floating piers. Into these the steamer dumped its burden; the goods were there sorted and then given over to the various small harbor lighters. But experience in English harbors had shown that quay walls with deep foundations, which allowed the ship to lie alongside the land and discharge into freight sheds, considerably hastened and cheapened the discharge of a cargo. Moreover, the rapid extension of railway transportation brought with it the need for direct contact between the ship and the railroad car.

These considerations made Hamburg decide to provide opportunity for its liners to come directly to land. English engineers were called upon to prepare plans for the construction of a modern harbor. In total disregard of the difference in conditions between London or Liverpool and Hamburg, they recommended closed docks with lock gates, like those of the English ports. In spite of the opposition of State Engineer Dalmann, the construction of such a dock was begun, but the superfluity of the entrance lock was seen before the construction was finished and it was never built in. As a result, Hamburg has today a system of open basins cut into the land, leaving solid piers projecting; it has not the English system of closed docks, with their hours of inactivity when ships and barges cannot get into the docks, or, if they are in, cannot get out.

Basins or „harbors“ (Hafen) were cut into the land because the cheaper process, prevalent in America, of building piers out into the water, was not practicable. Hamburg lies eighty-five miles distant from the open sea, up the river Elbe, and the river is here so narrow that the construction of projecting piers would have left insufficient width for a channel. But, for a reason which we shall consider later, most of the basins were made wide enough so that vessels could lie at the quays and discharge into freight sheds, while at the same time other ships tied up at a line of mooring posts, which bisects the basin longitudinally, and discharged into lighters and upcountry barges alongside. The first of these slips or basins, the Sandtorhafen, was opened in 1866. In the seventies the Grasbrookhafen was opened.

In the meanwhile, in 1871, the German Empire had been formed, into which Hamburg and Bremen entered only on condition that they should remain outside the Customs Union, consisting essentially of the members of the Empire. Germany developed rapidly, in an industrial way, and imports and exports for it began to be of greater significance for Hamburg than the old transshipment trade. After the independence of Belgium was attained, in the thirties, Antwerp awoke to a new commercial and maritime greatness, and, by the excellence of its new port facilities and the versatility of its steamship connections, was drawing heavily on the foi’eign trade of West Germany. It was time for the Elbe port to prepare for the needs of modern commerce. Bismarck had long importuned Hamburg to join the Customs Union. In 1882 it consented, ostensibly unwillingly. No doubt a leading ground for its consent was the fear that the exceptional tariffs which the German railways, under the leadership of Prussia, were granting to German seaports, would be withheld from one that persisted in remaining a foreign country.

However, a good bargain with the Empire was made, which retained for Hamburg many of the advantages that it had formerly enjoyed. The state of Hamburg, practically identical with the city of Hamburg, with 275,000 inhabitants, entered the Customs Union. Its harbor proper was to remain outside the Union and was to be rebuilt, isolated from the rest of the city. The Empire agreed to contribute forty million marks towards the construction of this Free Port.*) The remaining costabout one hundred and fifty milKon marks**) — has been borne by Hamburg.

The Sandtorhafen and the Grasbrookhafen had been built into a peninsula on the right— cityward— bank of the main Elbe stream. The whole peninsula, as well as the island of Kehrwieder between it and the city, was preempted for the Free Port. As no one was allowed to live there, 1,000 property owners were expropriated and 24,000 people made homeless.***) In this right-bank peninsula one more huge basin, the Baakenhafen, was constructed; 1,200 acres of marsh land were purchased on the left bank of the river and new basins excavated there. To the Free Port, opened in 1888, many additions have been made, all on the left bank, the last and greatest being the basins on Kuhwarder, built for and leased to the Hamburg-American Line.

*) Of course Hamburg sacrificed something when it came into the Customs Union. Her 900,000 inhabitants now pay the German duties —averaging perhaps 25 per cent— on imports. According to the terms of the agreement with the Empire, Hamburg must pay 1,700 men $1,000,000 a year to guard the Free Port. (Boston Society of Architects, page 24.)

**)Wiedenfeld: Hamburg als Welthafen, page 19.

***)Aftalion, page 505.

The Free Port consists of a large number of basins, lined by quay walls, alongside which steamers can lie and be discharged by cranes into freight sheds, amply supplied with railway connections. In the wide basins, mooring posts provide anchorage for ships handling cargo in the stream. There are warehouses directly on the waterside. Between the various left-bank basins are located shipyards and numerous exporting industries. The whole Free Port, therefore, considered by the customs department as foreign territory, includes land on either bank of the Elbe and the main river itself for a considerable distance. It is surrounded by a customs line, guarded by customs officials. On land the line is designated by high iron palings; along the river it is a floating palisade; where it crosses the river it is an imaginary line guarded at either end by the customs men. At the land and water entrances into the Free Port are provided customs booths, where goods must pay duty when they enter the Empire.

The first advantage of the Free Port is in facilitating re-exportation; indeed, the importance of the re-exportation trade is what, before all else, led to its creation. Merchandise can be brought free of duty into the Free Port, stored in its warehouses, repacked or mixed and then, as conditions of the market dictate, sent across the customs line into Germany or shipped to Scandinavia and the Baltic. In the Free Port foreign merchants can maintain sample or consignment stocks. Bonded warehouses do not offer the same opportunity for unhindered movement of merchandise within a port: everything must be done under the harassing control of customs men. In Hamburg there is no need of counting and verifying pieces when a reexportation is made. A bonded warehouse cannot offer the same facilities for various manipulations necessary to prepare goods for the consumer, such as cutting wines and mixing coffees.*)

The privilege of manufacturing in its Free Port, which Hamburg alone of all German ports possesses, is one that has proved of less benefit than was expected. Its advantage is of course that it allows exporting and outfitting industries to get their foreign raw materials duty free. This advantage has been partly overcome by the system of draw-backs since introduced and applied to manufacturers in the Customs Union: refunding to exporting manufacturers the duty paid on foreign raw materials contained in their manufactured products. The disadvantage under which all industries in the Free Port labor is that, if they wish to sell in Germany, they have to pay on their products crossing the customs line the high duty on manufactured articles, while their inland competitor has had to pay only a low duty on the corresponding raw materials. This disadvantage has become more marked as the home has come to preponderate over the foreign market.

Excepting shipyards, the industries in the Free Port have grown incomparably slower than those elsewhere in Hamburg and are of distinct types.**) They cater to the building, outfitting and provisioning of ships; such are

*) As a Hamburg merchant said, it is not so simple to make Javan from Brazilian coffee, in case of need. (Wiedenfeld: Die Welthafen, page 289.)

**) There are about 15,000 workmen employed in the Free Port, not more than 3,000 outside the shipyards.

shipyards, boiler shops, machine and repair shops and biscuit factories. Or they represent industries principally interested in exporting, such as rice mills and oil mills; or industries settled in the Free Port region before the Free Port was built.*) There has been complaint that manufacturers of inferior and „schwindelhaften“ wares have sought the Free Port out, in order to be free from the severe German official regulations.**)

*) The industries of the Free Port are located across the river from Hamburg. Provision had to be made for feeding the workmen there. This is accomplished by numerous restaurants (Kaffeehallen) under state control. As workmen may not live in the Free Port, there is maintained an elaborate ferry service between various parts of it and the city. In 1909 a tunnel was opened from Hamburg to Steinwarder, in the Free Port, where, among other establishments, the largest Hamburg shipyard, Blohm and Voss, is located.

**)Aftalion, page 195.

Perhaps the chief advantage of the Free Port lies in the facilities it offers for the rapid, frictionless discharging of ships with dutiable goods, whether destined for re-exportation or shipment inland. As Hamburg lies eighty-five miles from the sea, precautions must be taken to prevent goods being landed on the way up. The Hamburg pilot, who must be taken aboard when the vessel enters the Elbe, is sworn in as a customs inspector. Under his guidance the vessel comes up the river at any hour of day or night and passes to her berth in the Free Port, unmolested by customs officers. There are no summary or detailed declarations of dutiable goods to be made, no customs officers to be taken aboard, with the explanations and delays attendant on their presence. Where, as in England, their official hours are limited, a ship with dutiable wares must suspend the discharge of her cargo during night hours. In the Hamburg Free Port, she discharges and loads day and night, if she will. When she is ready, her inspector-pilot takes her out to sea; no officer of the customs has even been aboard. It is the least conceivable hindrance of the free movement of a ship.

There is of course no occasion for vessels engaged in the German coasting trade to enter the Free Port. They discharge on quays on the right bank of the Elbe, outside the Free Port district. Moreover, as the Elbe above and the Elbe below Hamburg are within the Customs Union and as part of the main stream is within the Free Port, barges plying between upper and lower Elbe would have to be examined after coming through the Free Port, if they were obliged to use the main stream for their passage. To obviate this necessity, the right bank peninsula, already mentioned, has been cut to form a belt canal, which acts as a partial boundary between the Free Port and the city, and through which the barge traffic between upper and lower Elbe plies unhindered. However, it is in the Free Port that the main part of Hamburg’s shipping is handled, and its facilities are those that interest us.

There is little essential difference between the various basins of the Free Port. A description of the newest and best, the piers of the Hamburg-American Line, will serve for all. The Hamburg-American piers were constructed by the state of Hamburg in the year 1903, at a cost of thirty-two million marks, and leased to the HamburgAmerican Line at a yearly rental of 1,350,000 marks.*) Three basins have been cut into an ancient meadow, the

*) Richter: Führer, page 63.

Kuhwärder, leaving two huge, solid piers projecting. The piers are lined with concrete quay walls, with foundations so deep that the berths are dredged to a depth of 32.8 feet, the high water depth of the channel. The solid piers are so wide that each carries two rows of sheds, one on either edge, as well as railroad tracks before and behind the sheds. One side of the longer pier has a length of 3,500 feet and carries three enormous pier sheds. In front of these, spanning the water-edge railroad tracks, are numerous electric cranes — one every 100 feet — with a lifting power of two tons each. They have a „halfportal“ form: a vertical leg runs on a rail on the very edge of the quay, a horizontal leg on a rail on the shed, just above the door.*) Cars and locomotives pass beneath the cranes, which are themselves movable longitudinally. Back of the shed, flush with the rear railway tracks, is a street, which may be used to dray goods to Hamburg or to near-by piers. Hand cranes serve to lower heavy pieces from the rear platform into car or dray. For handling freight within the pier shed, the HamburgAmerican Line is experimenting with electric trucks of the three-wheel type, capable of carrying 5,000 pounds each at a speed of four miles per hour. Each does the work of six men with the old hand trucks.

*) It is interesting to observe, in various German harbors, cranes representing successive stages in pier crane development. The earliest form was the stationary hand crane. Then came the stationary steam crane, disadvantageous because the vessel had to be moved to and fro to bring her hatches, one after the other, within reach of the crane. The stationary steam crane was followed by the movable steam crane — it was easier to move the crane than the ship. But the early movable steam crane took up the width of a railroad track on the pier edge, for itself. The next stage was the electric (or hydraulic) portal crane, which put the mechanism out of the way, seated on a portal that ran on rails outside the railroad tracks, which it spanned. The last stage was the half-portal crane, in which the inner leg of the portal is taken out of the way; the horizontal beam of the framework runs on the shed itself. Perhaps the highest stage of pier crane development is reached by the roof cranes at Liverpool. They run on the slanting roof of the pier shed, outside, and do not in any way interfere with the utilization of the space on the pier’s edge beneath.

Before a liner arrives, the import shed where she is to discharge and the export shed where she is to load are ready for her. Freight trains and drays have been unloaded on the front and rear platforms of the export shed, river barges and harbor lighters have lain alongside the quay and had their freight hoisted and swung across the railroad tracks to the shed platform by silent electric cranes. A big river barge — they average 600 to 800 tons capacity — cannot enter the seaship basins unless it has at least fifty tons of freight to exchange with a seaship; otherwise it must send a Httle harbor lighter — they average about sixty tons — to the ship.*) This prevents unnecessarily clogging up the basins with unwieldy river barges. Similarly, the import shed has been emptied for the liner by cars, lighters, drays and barges.

The liner ties up at her import berth. A swarm of pier cranes brings up goods from the hold and swings them across to the shed platform, whence they are trucked inside. There they are counted, sorted and arranged for shipment direct inland by barge or rail, or for sending by lighter or dray to warehouse or railroad station (lessthan-carload lots). If freight needs no sorting, it may be dropped by the crane into a freight car standing underneath. Similarly, goods destined per barge for points on the upper Elbe, on through bills of lading, may be dropped by the ship’s tackle overside directly into the barge.

*) Recently there is talk of increasing to 100 tons this minimum that a barge must have for a seaship in order to be allowed to approach it. Surely such regulation will be necessary for the harbor of New York, when the Barge Canal is finished and the Barge Canal Terminal is constructed in New York.