Development of Hamburg's Hinterland

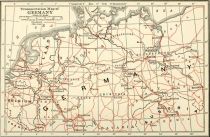

Nature of Hansa ports and their trade. Fall of the Hansa. Remains of its trade. Hamburg’s new position. Beginnings of free trade on the sea. Unifying Germany. Formation of the Empire. Economic development of Germany. The new industrial state. Imports and exports. Industry supplants agriculture. Proportion of foreign trade carried on by sea. Hamburg’s part in German foreign trade. Hamburg’s dependence today on her hinterland.

Chapter I - The Development of Hamburg’s Hinterland.

Until a short time ago Hamburg was primarily a transshipment harbor and an entrepot for the countries on the Baltic Sea. Such was the nature of the Hanseatic seaports, Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen. The Hansa was a loose league of North German cities whose merchants united to maintain common depots in foreign countries for collecting and distributing goods. The principal foreign depots were in London (the „Steelyard“), Bruges, Bergen and Novgorod. The Hanseatics controlled and carried the trade between Germany, the countries bordering on the Baltic and western Europe. They were able to monopolize this trade because for centuries the perilous voyage around the peninsula of Jutland was feared by merchant ships and because, when the sailors of the Hansa’s rivals dared make the voyage, the Hansa had for a time power to close the Baltic to rival ships. This forced a large part of the trade from the North to the Baltic Sea to pass from Hamburg to Lübeck by an inland waterway and made Lübeck, the Baltic terminal of this waterway, the leader of the Hanseatic League and the natural entrepot of the Baltic.

It was a considerable traffic, this between the wild East and the more cultured and developed West of Europe. From the fourteenth century on, Bruges, Antwerp, Amsterdam and London became each in turn the commercial center of northern Europe. The manufacture of woolen cloth grew up in Flanders and was later transplanted to England. These countries needed from eastern Europe grain, raw wool and wood for shipbuilding. Germany and the Baltic countries were purveyors of foodstuffs and raw materials to the more or less industrial northwestern Europe. French salt and wine, English and Flemish cloth and German knives were exchanged for wax, furs, Swedish ores, naval stores and other raw materials of the north and east, as well as Saxon and Silesian linen. Later, herring became the staple of the Baltic trade. So thoroughly was this commerce in the hands of the Hansa that the Scandinavian vikings, whose descendants play the second role in the European coasting trade today — after England — were driven from the sea. The fall of the power of the Hansa came when out of the political chaos in Europe nations arose like Holland and England with a naval power that they could use to further the interests of their own merchant marine. Against them the Hanseatics could not maintain their privileges.

It was this fact, not the discovery of America and the circumnavigation of Africa, which cost the Hansa towns their prosperity. Though the new discoveries brought into life a trade that was to dwarf that between East and West Europe, yet the latter trade remained. But it was no longer monopolized by the Hanseatic League. England led the way in sending her ships direct to Baltic ports without transshipment in Hamburg. The chief support of commerce from the Baltic, the herring fisheries, was removed when the herring changed his residence from the Baltic to the North Sea, there to become a bone of contention between the English and the Dutch. Though the monopoly of the Hanseatics was broken for all time, traces remain of their power today. A striking example of this is the position in the Baltic trade which Lübeck still holds. Certain wares from London to St. Petersburg still go via Lübeck.*) Hamburg, as we shall see, has today a heavy transshipment trade in Baltic countries in oversea goods, such as coffee, rice, tobacco, cacao and maize. The need for such a trade arises from no monopoly but from the fact that the Baltic countries have not sufficient trade with the oversea sources of these products to justify direct steamship lines thither. That Hamburg gets this transshipment trade is due largely to the fact that she has maintained through the centuries her ancient Hanseatic connections with the north and the east. Another factor that tends to make Hamburg the Baltic entrepot is that it is the farthest east of the great north European ports. Other things being equal, it is a law in ocean transportation that the transshipment trade prefers to attach itself to that port which allows goods the longest use of the cheaper ocean liner, before transshipment into the dearer coasting vessel or „short trader.“

*) Schäfer: Article „Hansa“ in Handworterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, Jena, 1892.

Though Hamburg, like the other Hanseatics, felt the loss of the monopoly of trade between East and West Europe, she was in a better position than Lübeck to take part in the new commerce with Asia and America. As regards this commerce, Lübeck was in a cul-de-sac, while Hamburg faced toward the Atlantic Ocean where the new trade routes lay. But Hamburg was for centuries destined to a subordinate rôle in this new commerce which was soon to preponderate over all others. Portugal, Spain, France, Holland and England jealously guarded the trade with their oversea colonies — and they owned the oversea world. Hamburg had to be satisfied with such crumbs as fell from the richly laden tables of the merchants of Lisbon, Cadiz, Amsterdam and London.

It was by acting as middleman between these rich emporia (particularly London) on the one hand, and Russia, the Scandinavian countries and Germany on the other, that Hamburg supported herself through the centuries that elapsed between her old supremacy and her new. It was Hamburg’s duty to be on good terms with the countries having oversea colonies, in order to be admitted to the European carrying trade on at least an equal footing with all rivals. In rare cases Hamburg ships were even allowed to join the convoyed fleets that plied between European ports and the colonies. The demands on Hamburg’s diplomacy were often great and her diplomacy had no naval power to back it. In 1670 the tattered German Empire had no ships, Hamburg had two convoys which escorted her merchantmen to meet the returning colonial fleets. At the same time Holland had 91 warships with crews totaling 23,500 men, England had 173 warships with 43,000 men aboard. An instance illustrates the difficulties which the Hamburg senators had to face. In 1666 the Dutch Admiral Brederode sailed up the Elbe, destroyed one Hamburg and several English ships. England threatened reprisals if Hamburg did not pay indemnity for the losses which England had sustained. Hamburg saw herself forced to give in.*)

*) R. Ehrenberg: Hamburgs Handel und Schiffahrt.

As Spain’s power and her hold on her American colonies weakened, Hamburg did a thriving smuggling trade with South America and the West Indies, staples being coffee, sugar, Brazilian pepper, indigo and dye woods. Hamburg plantations, which still endure, were established in Central America and the West Indies. In 1789 there were 5,000 men employed in the sugar refineries of Hamburg, which supplied the kingdoms of the North with sugar and manufactured tobacco.*) A similar smuggling trade was a source of rich profit to Hamburg merchants during the American Revolution. The new United States of America were the first great foreign field open to Hamburg. When Mexico and the South American dependencies of Portugal and Spain revolted, Hamburg merchants exclaimed joyfully, „Hamburg has colonies at last.“ There was one great hiatus in this development: the years 1806-14, when the French occupied Hamburg, while Napoleon by his Berlin Decree and England by her retaliatory measure of blockading the Elbe shut off the port’s communication with the outside world.

*) Plath, page 99.

Apart from this period the first half of the nineteenth century was a time of steady progress. Those oversea colonies which had not revolted were gradually given freedom to trade direct with the European countries; the old policy of repression had not had happy results. More important still, there was growing up behind Hamburg an industrial hinterland, which was to become her sure basis of prosperity. Ever since the Peace of Westphalia, in 1648, Germany had been split up among a hundred princelings, each with his own customs line, his own road and river tolls. There was no possibility of anything but local trade. But in the twenties the German Customs Union was formed under the leadership of Prussia, eager to make a market for her promising industries. The Customs Union spread until by the middle of the century it included the greater part of Germany. As customs barriers fell, traffic tolls — there was a toll to pay every few miles on the Elbe — were cut down, the Elbe being declared toll-free in 1870. Beginning with the foi’ties railroads were built, for the first time bringing within reach of Hamburg towns and districts not on the Elbe or its connecting waterways.*)

Important as were the building of railroads and the work of the Customs Union in making the interior of the country accessible, leveling tariff walls and giving a field of expansion for German industries, it was not until after the formation of the Empire in 1871 that Germany was sufficiently interested in foreign trade to become the basis of a new prosperity in Hamburg. As late as 1869, 60 per cent of the register tonnage of ships that entered Hamburg came from England, only 15 per cent from the rest of Europe.**) That meant that Hamburg was still playing middleman for London. Napoleon characterized Hamburg when he exclaimed, “Ne me parlez pas de cette ville anglaise“; until recent years there were Hamburgers who were proud that they had never been in Berlin. In 1871, when Hamburg and Bremen entered the German Empire, they stipulated that they should remain outside the Customs Union. Their transshipment trade still prevailed.

*) At the beginning of the nineteenth century the dry land behind Hamburg was thought of less as a source of commerce than as a source of marauding expeditions. The marshes that isolated Hamburg and Antwerp from the land were looked upon as advantages in that they made the cities inaccessible to robbers. In 1804 Hamburg on either side of the Elbe was surrounded by high walls, their continuation across the Elbe being represented by booms, obstructions preventing the passing of boats. From sunset to sunrise the gates were closed, the booms swung across the river and the city locked up hard and fast for the night. From January 1 to 12, according to the official almanac, this period from sunset to sunrise lasted from 4.15 p.m. to 8 a.m. Communication inland was solely by the Elbe and its tributaries.

**) Wiendenfeld, Hamburg, page 10.

After the formation of the Empire a new order of things dawned. Five billion francs of indemnity from the defeated French poured into the country. There were imported the industrial processes that England had developed: the automatic loom, the blast furnace for pig iron, the Bessemer converter for steel. In 1879, Germany enacted a protective tariff to develop her industries and save her threatened agriculture, against which the grain of the American prairies was flowing in. Both manufactures and agriculture responded to the opportunity. There was occurring in the economic world an interlocal and international specialization of labor that resulted in an enormous exchange of goods by sea. Cheapened production and cheap transportation made possible the exchange of goods that had never moved from the spot before. It was this change in Germany’s economic life that decided Hamburg to accede to the importunities of Bismarck and enter the Customs Union. Yet so strongly did the belief in the old transshipment trade persist that the greater part of the port was fenced off and set apart, to remain a Free Port, outside the Customs Union, just as the whole city had been outside of the Union before.

The protective duty on meat has encouraged cattleraising; that meant imported cottonseed cakes from America, maize from America and the Argentine to fatten stall-fed cattle. The protective duty on grain has encouraged the fertilization of agricultural lands; that brought with it imports of Chili saltpetre and guano and of phosphates from Florida. A similar demand abroad led to the exportation of potash from the inexhaustible German fields on the Elbe. The perfection of the process of manufacturing sugar from the sugar beet resulted in Germany becoming the world’s first producer and a heavy exporter of the article.*) Finally, the change during the nineteenth century from the use of wood to the use of coal for industrial and domestic firing led to a movement of coal that has become the backbone of commerce. In 1907, 40 per cent of the traffic tonnage on the German railways consisted of coal and coke; four and one half million tons imported coal constituted one third of the tonnage of the imports of Hamburg.

Yet Germany could not be made capable of supporting the enormous increase in her population, which rose from forty million in 1870 to sixty-five million in 1910 — at the rate of 900,000 per year the last ten years. Nor is this surplus considerably reduced by emigration, as formerly.**)

*) Production of beet sugar, year 1906-07:

Germany: 2,235,000 tons

Austro-Hungary: 1,334,000 tons

France: 756,000 tons

Belgium: 283,000 tons

Holland: 181,000 tons

Russia: 1,470,000 tons

Other Lands: 445,000 tons

(Hamburgs Handel, 1907.)

Throughout this book, “ton” means a metric ton, 2,204 English pounds.

**) Yet in the years 1881-90, the years of the heaviest emigration, only 24 per cent of .the natural increase of population were carried off. Since 1895 there is an excess of immigration. In the years 1871-95, the excess of emigration over immigration was two and one German emigration dropped from such figures as 210,000 in 1881 and 250,000 in 1882 to 32,000 in 1895 and has never since passed 50,000. The acreage of German soil sown with grain increases but slightly. The yields of wheat, barley, rye and hay have not increased in the last decade in spite of higher protective duties. The production of grain in Germany seems to have reached the saturation point and an increasingly large portion of the yearly consumption of grain must come from America, Argentine, Roumania and Russia. The figures for the national production and the importation of wheat indicate this.

Sources of Germany’s Wheat Supply.*)

Value of Imports

Raised Imported Million Marks

1899 . . 3,847,447 tons 1,370,051 tons 180

1903 . . 3,555,064 tons 2,124,643 tons 253

1907 . . 3,479,324 tons 2,634,889 tons 385

To pay for this great increase in imported foodstuffs, Germany has had to export manufactured goods. How successfully she has met this need is seen in the following table, indicating the increase of her exported manufactures since 1890.

Exports and Imports of Manufactured Articles.

Million Marks

Exports Imports

1890 . . . 2,148 981

1899 . . . 2,712 1,148

1907 . . . 4,638 1,392

half million persons; in the years 1895-1900, 94,000 more emigrants settled in Germany than left it. (Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reichs, and Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen.)

*) Statistische Jahrbücher für das deutsche Reich.

Moreover, the raw materials for many of these manufactures come from oversea; for Instance, the raw materials for cotton, woolen and silk goods. Germany’s imports of raw cotton have increased within recent years as follows:*)

Imports of Raw Cottox.

Million Marks**)

1901 296

1903 395

1907 551

Germany is fast becoming a typical industrial country; that is, a country engaged in importing the raw materials of industry and foodstuffs for supporting a population that pays for these imports by exporting its manufactured products. This is apparent from a consideration of the following table, which shows the enormous growth of foreign trade since 1890 and the principal items of export and import in the year 1907.

Growth of Germany’s Exports and Imports.

Million Marks

Imports Exports

1890 . . . 2,860 2,946

1899 . . . 5,786 4,364

1907 . . . 8,747 6,845

*) Statistische Jahrbücher für das deutsche Reich. In the period 1894-1904 Germany’s foreign trade increased 66 per cent, England’s 38 per cent, the United States’ 59 per cent, France’s 28 per cent, Russia’s 23 per cent.

**) A mark is 23.8 cents. In rough reckoning it is convenient to consider it 25 cents. There are 100 pfennigs in a mark. A pfennig is roughly one fourth cent.

Leading Items.

IMPORTS EXPORTS.

Cotton, 551 Cotton Goods, 432

Wool, 394 Machines, 412

Wheat, 385 Chemical Products, 350

Barley, 282 Coal, 280

Coal, 242 Woolen Goods, 286

Copper, 240 Silk Goods, 204

Sugar, 193

An analysis of the population of Germany by occupations according to the censuses of 1882, 1895 and 1907, respectively, shows that the surplus of population is being cared for primarily by industrial employment. Only the three principal occupations — industry, commerce and agriculture — need be considered. The percentages are percentages of the total population.*)

*) Statistische Jahrbücher für das deutsche Reich.

Occupations of German Population.

Employed in 1882 1895 1907

Agriculture, 19,225,455 18,501,307 17,681,176

Manufacturing, 16,058,080 20,253,241 26,386,537

Commerce, 4,531,080 5,966,846 8,278,239

percentages.

1882 1895 1907

Agriculture, 42.5 36.2 33.7

Manufacturing, 35.5 36.1 37.2

Commerce, 10. 10.2 11.5

Germany is a continental state, centrally situated in Europe, with long terrestial borders and a comparatively short coast line. Yet an extraordinarily large part of her foreign commerce is by sea. All of the leading items of her imports, given above, are from oversea, as are colonial wares such as coffee, tea, rice, tobacco. Similarly, her markets for manufactured goods are mostly across the water: either In such free trade lands as England, South America, India and China, or In the wealthy United States. Of Germany’s 15,592,000,000 marks of foreign trade In 1907, 34.5 per cent*) were with extra-European countries, 18 per cent more were with England and Scandinavian countries and hence carried on by sea. Moreover, a large commerce with European countries goes by sea: that with countries bordering on the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Finally, a large portion of Germany’s foreign trade Is carried on via Rotterdam and Antwerp, which act as seaports for the industrial West Germany. Thus one third of the volume of Germany’s oversea exports and imports appears in the statistics as destined for or coming from Holland and Belgium.**) A German official publication, „Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen,“ estimates that 70 per cent of Germany’s foreign trade is by sea. The meaning becomes clear of that watchword which the Kaiser gave out at the dedication of the new harbor at Stettin: “unsere Zukunft liegt auf dem Wasser.“

*) This percentage was 31.5 per cent in 1904, 28.2 per cent in 1898, 27.1 per cent in 1894.

**) Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen. Einleitung, VI.

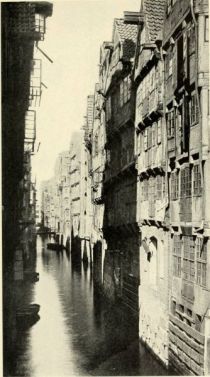

A row of old warehouses on the Steckelhorn, one of Hamburg’s ancient canals.

The interest of Hamburg in this development is apparent when we consider that Hamburg’s natural and immediate hinterland is the seat of the beet sugar industry, Intensive farming and cattle-raising and that Germany’s potash deposits lie on the banks of the Elbe, Hamburg’s stream, and on the Saale, Its tributary. On the Elbe and its connecting waterways are such manufacturing centers as Magdeburg and Dresden, Berlin and Breslau — and back of the latter the Silesian industrial district. The Saxon industrial district finds in Hamburg its natural outlet. The industries of Westphalia are brought within Hamburg’s sphere of influence by favorable railway tariffs. The result has been that Hamburg’s commerce by sea has increased even more rapidly than Germany’s population and Germany’s foreign trade; i.e., that Hamburg handles a continually larger portion of that foreign trade.

Growth of Germany’s Foreign Trade and Hamburg’s Part Therein.*)

Index Numbers

German German Hamburg’s German German Hamburg

Population Foreign Seaward Population Trade Trade

Trade Trade**)

Marks Marks

1880 45,095,000 5,805,100,000 1,700,100,000 100 100 100

1907 62,000,000 15,586,000,000 6,397,500,000 137 269 376

*) Statistisches Jahrbuch, Hamburgs Handel und Schiffahrt, Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reichs.

**) This includes goods exchanged with German ports in the coasting trade. However, it is fair to assume that the proportion of the coasting trade in the total is the same for both years.

Exports and imports for Hamburg’s hinterland now dwarf into insignificance the transshipment trade to Scandinavia, Russia and the Baltic provinces. Direct lines are employed to carry goods between Hamburg and oversea; the English middleman has been shaken off. The process of emancipation from the English middleman is graphically illustrated by the following table:

Source of Imports in Hamburg.*)

Million Marks

1871-80 1896 1907

Non-European Lands, 262 958 2,222

United Kingdom, 474 410 635

Rest of Europe, 139 345 1,355

This increase in imports direct from oversea lands is not for transshipment. It is for Germany’s intensive cultivation of her soil that the immense quantities of Chilean nitrate arrive in Hamburg; the shiploads of maize from Baltimore are to become German beef. The colliers that ply between Newcastle and Hamburg are bringing fuel for the industries of Hamburg and Berlin and bunker coal for half the German merchant marine. Millions of tons of grain, thousands of tons of coffee are brought to feed the workers that are to transform the bales of cotton, the Australian wool and East Indian jute, the iron pyrites from Spain, the American and African woods that are piled high on the quays and in the pier sheds of Hamburg.

And so with the exports that we see leaving Hamburg. The sacks of sugar that are being loaded into the ships came from the scientifically cultivated fields of Silesia, Prussian Saxony and Bohemia; the barrels of alcohol are from the distilleries of Brandenburg and Pomerania. The heavy iron work and the machines, shipments of cotton and woolen wares, cases of leather goods and glassware, the miscellany of chemical products, are from German workshops. The potash, salts and coal that ballast the outgoing ships come from German soil.

*) Statistisches Jahrbuch, 1907, and Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reichs.

The old Hanseatic seaport, turned exclusively toward the sea, has become a new one turned toward Germany — become a part of Germany and dependent on it. When an ambitious Frenchman inquired in Hamburg how Nantes could follow the example of Hamburg, he received the reply: „You must commence by transforming at least Orleans, Tours, Blois, Saumur and Angers into cities of from 200,000 to 300,000 inhabitants and cover with factories the country roundabout. Then perhaps Nantes will be able to follow the example of Hamburg.“*) The new prosperity of Hamburg has its basis in the prosperity of the new Germany.

*) Paul de Rousiers, page 177.

Chapter I - The Development of Hamburg’s Hinterland.

Until a short time ago Hamburg was primarily a transshipment harbor and an entrepot for the countries on the Baltic Sea. Such was the nature of the Hanseatic seaports, Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen. The Hansa was a loose league of North German cities whose merchants united to maintain common depots in foreign countries for collecting and distributing goods. The principal foreign depots were in London (the „Steelyard“), Bruges, Bergen and Novgorod. The Hanseatics controlled and carried the trade between Germany, the countries bordering on the Baltic and western Europe. They were able to monopolize this trade because for centuries the perilous voyage around the peninsula of Jutland was feared by merchant ships and because, when the sailors of the Hansa’s rivals dared make the voyage, the Hansa had for a time power to close the Baltic to rival ships. This forced a large part of the trade from the North to the Baltic Sea to pass from Hamburg to Lübeck by an inland waterway and made Lübeck, the Baltic terminal of this waterway, the leader of the Hanseatic League and the natural entrepot of the Baltic.

It was a considerable traffic, this between the wild East and the more cultured and developed West of Europe. From the fourteenth century on, Bruges, Antwerp, Amsterdam and London became each in turn the commercial center of northern Europe. The manufacture of woolen cloth grew up in Flanders and was later transplanted to England. These countries needed from eastern Europe grain, raw wool and wood for shipbuilding. Germany and the Baltic countries were purveyors of foodstuffs and raw materials to the more or less industrial northwestern Europe. French salt and wine, English and Flemish cloth and German knives were exchanged for wax, furs, Swedish ores, naval stores and other raw materials of the north and east, as well as Saxon and Silesian linen. Later, herring became the staple of the Baltic trade. So thoroughly was this commerce in the hands of the Hansa that the Scandinavian vikings, whose descendants play the second role in the European coasting trade today — after England — were driven from the sea. The fall of the power of the Hansa came when out of the political chaos in Europe nations arose like Holland and England with a naval power that they could use to further the interests of their own merchant marine. Against them the Hanseatics could not maintain their privileges.

It was this fact, not the discovery of America and the circumnavigation of Africa, which cost the Hansa towns their prosperity. Though the new discoveries brought into life a trade that was to dwarf that between East and West Europe, yet the latter trade remained. But it was no longer monopolized by the Hanseatic League. England led the way in sending her ships direct to Baltic ports without transshipment in Hamburg. The chief support of commerce from the Baltic, the herring fisheries, was removed when the herring changed his residence from the Baltic to the North Sea, there to become a bone of contention between the English and the Dutch. Though the monopoly of the Hanseatics was broken for all time, traces remain of their power today. A striking example of this is the position in the Baltic trade which Lübeck still holds. Certain wares from London to St. Petersburg still go via Lübeck.*) Hamburg, as we shall see, has today a heavy transshipment trade in Baltic countries in oversea goods, such as coffee, rice, tobacco, cacao and maize. The need for such a trade arises from no monopoly but from the fact that the Baltic countries have not sufficient trade with the oversea sources of these products to justify direct steamship lines thither. That Hamburg gets this transshipment trade is due largely to the fact that she has maintained through the centuries her ancient Hanseatic connections with the north and the east. Another factor that tends to make Hamburg the Baltic entrepot is that it is the farthest east of the great north European ports. Other things being equal, it is a law in ocean transportation that the transshipment trade prefers to attach itself to that port which allows goods the longest use of the cheaper ocean liner, before transshipment into the dearer coasting vessel or „short trader.“

*) Schäfer: Article „Hansa“ in Handworterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, Jena, 1892.

Though Hamburg, like the other Hanseatics, felt the loss of the monopoly of trade between East and West Europe, she was in a better position than Lübeck to take part in the new commerce with Asia and America. As regards this commerce, Lübeck was in a cul-de-sac, while Hamburg faced toward the Atlantic Ocean where the new trade routes lay. But Hamburg was for centuries destined to a subordinate rôle in this new commerce which was soon to preponderate over all others. Portugal, Spain, France, Holland and England jealously guarded the trade with their oversea colonies — and they owned the oversea world. Hamburg had to be satisfied with such crumbs as fell from the richly laden tables of the merchants of Lisbon, Cadiz, Amsterdam and London.

It was by acting as middleman between these rich emporia (particularly London) on the one hand, and Russia, the Scandinavian countries and Germany on the other, that Hamburg supported herself through the centuries that elapsed between her old supremacy and her new. It was Hamburg’s duty to be on good terms with the countries having oversea colonies, in order to be admitted to the European carrying trade on at least an equal footing with all rivals. In rare cases Hamburg ships were even allowed to join the convoyed fleets that plied between European ports and the colonies. The demands on Hamburg’s diplomacy were often great and her diplomacy had no naval power to back it. In 1670 the tattered German Empire had no ships, Hamburg had two convoys which escorted her merchantmen to meet the returning colonial fleets. At the same time Holland had 91 warships with crews totaling 23,500 men, England had 173 warships with 43,000 men aboard. An instance illustrates the difficulties which the Hamburg senators had to face. In 1666 the Dutch Admiral Brederode sailed up the Elbe, destroyed one Hamburg and several English ships. England threatened reprisals if Hamburg did not pay indemnity for the losses which England had sustained. Hamburg saw herself forced to give in.*)

*) R. Ehrenberg: Hamburgs Handel und Schiffahrt.

As Spain’s power and her hold on her American colonies weakened, Hamburg did a thriving smuggling trade with South America and the West Indies, staples being coffee, sugar, Brazilian pepper, indigo and dye woods. Hamburg plantations, which still endure, were established in Central America and the West Indies. In 1789 there were 5,000 men employed in the sugar refineries of Hamburg, which supplied the kingdoms of the North with sugar and manufactured tobacco.*) A similar smuggling trade was a source of rich profit to Hamburg merchants during the American Revolution. The new United States of America were the first great foreign field open to Hamburg. When Mexico and the South American dependencies of Portugal and Spain revolted, Hamburg merchants exclaimed joyfully, „Hamburg has colonies at last.“ There was one great hiatus in this development: the years 1806-14, when the French occupied Hamburg, while Napoleon by his Berlin Decree and England by her retaliatory measure of blockading the Elbe shut off the port’s communication with the outside world.

*) Plath, page 99.

Apart from this period the first half of the nineteenth century was a time of steady progress. Those oversea colonies which had not revolted were gradually given freedom to trade direct with the European countries; the old policy of repression had not had happy results. More important still, there was growing up behind Hamburg an industrial hinterland, which was to become her sure basis of prosperity. Ever since the Peace of Westphalia, in 1648, Germany had been split up among a hundred princelings, each with his own customs line, his own road and river tolls. There was no possibility of anything but local trade. But in the twenties the German Customs Union was formed under the leadership of Prussia, eager to make a market for her promising industries. The Customs Union spread until by the middle of the century it included the greater part of Germany. As customs barriers fell, traffic tolls — there was a toll to pay every few miles on the Elbe — were cut down, the Elbe being declared toll-free in 1870. Beginning with the foi’ties railroads were built, for the first time bringing within reach of Hamburg towns and districts not on the Elbe or its connecting waterways.*)

Important as were the building of railroads and the work of the Customs Union in making the interior of the country accessible, leveling tariff walls and giving a field of expansion for German industries, it was not until after the formation of the Empire in 1871 that Germany was sufficiently interested in foreign trade to become the basis of a new prosperity in Hamburg. As late as 1869, 60 per cent of the register tonnage of ships that entered Hamburg came from England, only 15 per cent from the rest of Europe.**) That meant that Hamburg was still playing middleman for London. Napoleon characterized Hamburg when he exclaimed, “Ne me parlez pas de cette ville anglaise“; until recent years there were Hamburgers who were proud that they had never been in Berlin. In 1871, when Hamburg and Bremen entered the German Empire, they stipulated that they should remain outside the Customs Union. Their transshipment trade still prevailed.

*) At the beginning of the nineteenth century the dry land behind Hamburg was thought of less as a source of commerce than as a source of marauding expeditions. The marshes that isolated Hamburg and Antwerp from the land were looked upon as advantages in that they made the cities inaccessible to robbers. In 1804 Hamburg on either side of the Elbe was surrounded by high walls, their continuation across the Elbe being represented by booms, obstructions preventing the passing of boats. From sunset to sunrise the gates were closed, the booms swung across the river and the city locked up hard and fast for the night. From January 1 to 12, according to the official almanac, this period from sunset to sunrise lasted from 4.15 p.m. to 8 a.m. Communication inland was solely by the Elbe and its tributaries.

**) Wiendenfeld, Hamburg, page 10.

After the formation of the Empire a new order of things dawned. Five billion francs of indemnity from the defeated French poured into the country. There were imported the industrial processes that England had developed: the automatic loom, the blast furnace for pig iron, the Bessemer converter for steel. In 1879, Germany enacted a protective tariff to develop her industries and save her threatened agriculture, against which the grain of the American prairies was flowing in. Both manufactures and agriculture responded to the opportunity. There was occurring in the economic world an interlocal and international specialization of labor that resulted in an enormous exchange of goods by sea. Cheapened production and cheap transportation made possible the exchange of goods that had never moved from the spot before. It was this change in Germany’s economic life that decided Hamburg to accede to the importunities of Bismarck and enter the Customs Union. Yet so strongly did the belief in the old transshipment trade persist that the greater part of the port was fenced off and set apart, to remain a Free Port, outside the Customs Union, just as the whole city had been outside of the Union before.

The protective duty on meat has encouraged cattleraising; that meant imported cottonseed cakes from America, maize from America and the Argentine to fatten stall-fed cattle. The protective duty on grain has encouraged the fertilization of agricultural lands; that brought with it imports of Chili saltpetre and guano and of phosphates from Florida. A similar demand abroad led to the exportation of potash from the inexhaustible German fields on the Elbe. The perfection of the process of manufacturing sugar from the sugar beet resulted in Germany becoming the world’s first producer and a heavy exporter of the article.*) Finally, the change during the nineteenth century from the use of wood to the use of coal for industrial and domestic firing led to a movement of coal that has become the backbone of commerce. In 1907, 40 per cent of the traffic tonnage on the German railways consisted of coal and coke; four and one half million tons imported coal constituted one third of the tonnage of the imports of Hamburg.

Yet Germany could not be made capable of supporting the enormous increase in her population, which rose from forty million in 1870 to sixty-five million in 1910 — at the rate of 900,000 per year the last ten years. Nor is this surplus considerably reduced by emigration, as formerly.**)

*) Production of beet sugar, year 1906-07:

Germany: 2,235,000 tons

Austro-Hungary: 1,334,000 tons

France: 756,000 tons

Belgium: 283,000 tons

Holland: 181,000 tons

Russia: 1,470,000 tons

Other Lands: 445,000 tons

(Hamburgs Handel, 1907.)

Throughout this book, “ton” means a metric ton, 2,204 English pounds.

**) Yet in the years 1881-90, the years of the heaviest emigration, only 24 per cent of .the natural increase of population were carried off. Since 1895 there is an excess of immigration. In the years 1871-95, the excess of emigration over immigration was two and one German emigration dropped from such figures as 210,000 in 1881 and 250,000 in 1882 to 32,000 in 1895 and has never since passed 50,000. The acreage of German soil sown with grain increases but slightly. The yields of wheat, barley, rye and hay have not increased in the last decade in spite of higher protective duties. The production of grain in Germany seems to have reached the saturation point and an increasingly large portion of the yearly consumption of grain must come from America, Argentine, Roumania and Russia. The figures for the national production and the importation of wheat indicate this.

Sources of Germany’s Wheat Supply.*)

Value of Imports

Raised Imported Million Marks

1899 . . 3,847,447 tons 1,370,051 tons 180

1903 . . 3,555,064 tons 2,124,643 tons 253

1907 . . 3,479,324 tons 2,634,889 tons 385

To pay for this great increase in imported foodstuffs, Germany has had to export manufactured goods. How successfully she has met this need is seen in the following table, indicating the increase of her exported manufactures since 1890.

Exports and Imports of Manufactured Articles.

Million Marks

Exports Imports

1890 . . . 2,148 981

1899 . . . 2,712 1,148

1907 . . . 4,638 1,392

half million persons; in the years 1895-1900, 94,000 more emigrants settled in Germany than left it. (Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reichs, and Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen.)

*) Statistische Jahrbücher für das deutsche Reich.

Moreover, the raw materials for many of these manufactures come from oversea; for Instance, the raw materials for cotton, woolen and silk goods. Germany’s imports of raw cotton have increased within recent years as follows:*)

Imports of Raw Cottox.

Million Marks**)

1901 296

1903 395

1907 551

Germany is fast becoming a typical industrial country; that is, a country engaged in importing the raw materials of industry and foodstuffs for supporting a population that pays for these imports by exporting its manufactured products. This is apparent from a consideration of the following table, which shows the enormous growth of foreign trade since 1890 and the principal items of export and import in the year 1907.

Growth of Germany’s Exports and Imports.

Million Marks

Imports Exports

1890 . . . 2,860 2,946

1899 . . . 5,786 4,364

1907 . . . 8,747 6,845

*) Statistische Jahrbücher für das deutsche Reich. In the period 1894-1904 Germany’s foreign trade increased 66 per cent, England’s 38 per cent, the United States’ 59 per cent, France’s 28 per cent, Russia’s 23 per cent.

**) A mark is 23.8 cents. In rough reckoning it is convenient to consider it 25 cents. There are 100 pfennigs in a mark. A pfennig is roughly one fourth cent.

Leading Items.

IMPORTS EXPORTS.

Cotton, 551 Cotton Goods, 432

Wool, 394 Machines, 412

Wheat, 385 Chemical Products, 350

Barley, 282 Coal, 280

Coal, 242 Woolen Goods, 286

Copper, 240 Silk Goods, 204

Sugar, 193

An analysis of the population of Germany by occupations according to the censuses of 1882, 1895 and 1907, respectively, shows that the surplus of population is being cared for primarily by industrial employment. Only the three principal occupations — industry, commerce and agriculture — need be considered. The percentages are percentages of the total population.*)

*) Statistische Jahrbücher für das deutsche Reich.

Occupations of German Population.

Employed in 1882 1895 1907

Agriculture, 19,225,455 18,501,307 17,681,176

Manufacturing, 16,058,080 20,253,241 26,386,537

Commerce, 4,531,080 5,966,846 8,278,239

percentages.

1882 1895 1907

Agriculture, 42.5 36.2 33.7

Manufacturing, 35.5 36.1 37.2

Commerce, 10. 10.2 11.5

Germany is a continental state, centrally situated in Europe, with long terrestial borders and a comparatively short coast line. Yet an extraordinarily large part of her foreign commerce is by sea. All of the leading items of her imports, given above, are from oversea, as are colonial wares such as coffee, tea, rice, tobacco. Similarly, her markets for manufactured goods are mostly across the water: either In such free trade lands as England, South America, India and China, or In the wealthy United States. Of Germany’s 15,592,000,000 marks of foreign trade In 1907, 34.5 per cent*) were with extra-European countries, 18 per cent more were with England and Scandinavian countries and hence carried on by sea. Moreover, a large commerce with European countries goes by sea: that with countries bordering on the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Finally, a large portion of Germany’s foreign trade Is carried on via Rotterdam and Antwerp, which act as seaports for the industrial West Germany. Thus one third of the volume of Germany’s oversea exports and imports appears in the statistics as destined for or coming from Holland and Belgium.**) A German official publication, „Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen,“ estimates that 70 per cent of Germany’s foreign trade is by sea. The meaning becomes clear of that watchword which the Kaiser gave out at the dedication of the new harbor at Stettin: “unsere Zukunft liegt auf dem Wasser.“

*) This percentage was 31.5 per cent in 1904, 28.2 per cent in 1898, 27.1 per cent in 1894.

**) Die Entwicklung der deutschen Seeinteressen. Einleitung, VI.

A row of old warehouses on the Steckelhorn, one of Hamburg’s ancient canals.

The interest of Hamburg in this development is apparent when we consider that Hamburg’s natural and immediate hinterland is the seat of the beet sugar industry, Intensive farming and cattle-raising and that Germany’s potash deposits lie on the banks of the Elbe, Hamburg’s stream, and on the Saale, Its tributary. On the Elbe and its connecting waterways are such manufacturing centers as Magdeburg and Dresden, Berlin and Breslau — and back of the latter the Silesian industrial district. The Saxon industrial district finds in Hamburg its natural outlet. The industries of Westphalia are brought within Hamburg’s sphere of influence by favorable railway tariffs. The result has been that Hamburg’s commerce by sea has increased even more rapidly than Germany’s population and Germany’s foreign trade; i.e., that Hamburg handles a continually larger portion of that foreign trade.

Growth of Germany’s Foreign Trade and Hamburg’s Part Therein.*)

Index Numbers

German German Hamburg’s German German Hamburg

Population Foreign Seaward Population Trade Trade

Trade Trade**)

Marks Marks

1880 45,095,000 5,805,100,000 1,700,100,000 100 100 100

1907 62,000,000 15,586,000,000 6,397,500,000 137 269 376

*) Statistisches Jahrbuch, Hamburgs Handel und Schiffahrt, Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reichs.

**) This includes goods exchanged with German ports in the coasting trade. However, it is fair to assume that the proportion of the coasting trade in the total is the same for both years.

Exports and imports for Hamburg’s hinterland now dwarf into insignificance the transshipment trade to Scandinavia, Russia and the Baltic provinces. Direct lines are employed to carry goods between Hamburg and oversea; the English middleman has been shaken off. The process of emancipation from the English middleman is graphically illustrated by the following table:

Source of Imports in Hamburg.*)

Million Marks

1871-80 1896 1907

Non-European Lands, 262 958 2,222

United Kingdom, 474 410 635

Rest of Europe, 139 345 1,355

This increase in imports direct from oversea lands is not for transshipment. It is for Germany’s intensive cultivation of her soil that the immense quantities of Chilean nitrate arrive in Hamburg; the shiploads of maize from Baltimore are to become German beef. The colliers that ply between Newcastle and Hamburg are bringing fuel for the industries of Hamburg and Berlin and bunker coal for half the German merchant marine. Millions of tons of grain, thousands of tons of coffee are brought to feed the workers that are to transform the bales of cotton, the Australian wool and East Indian jute, the iron pyrites from Spain, the American and African woods that are piled high on the quays and in the pier sheds of Hamburg.

And so with the exports that we see leaving Hamburg. The sacks of sugar that are being loaded into the ships came from the scientifically cultivated fields of Silesia, Prussian Saxony and Bohemia; the barrels of alcohol are from the distilleries of Brandenburg and Pomerania. The heavy iron work and the machines, shipments of cotton and woolen wares, cases of leather goods and glassware, the miscellany of chemical products, are from German workshops. The potash, salts and coal that ballast the outgoing ships come from German soil.

*) Statistisches Jahrbuch, 1907, and Die Seeinteressen des deutschen Reichs.

The old Hanseatic seaport, turned exclusively toward the sea, has become a new one turned toward Germany — become a part of Germany and dependent on it. When an ambitious Frenchman inquired in Hamburg how Nantes could follow the example of Hamburg, he received the reply: „You must commence by transforming at least Orleans, Tours, Blois, Saumur and Angers into cities of from 200,000 to 300,000 inhabitants and cover with factories the country roundabout. Then perhaps Nantes will be able to follow the example of Hamburg.“*) The new prosperity of Hamburg has its basis in the prosperity of the new Germany.

*) Paul de Rousiers, page 177.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches The Port of Hamburg.

01. Row of buildings of the Free Port Warehousing Company

02. Transportation map of Germany

03. Hamburg freighter, being served by barges and lighters.

04. The Steekelhorn, one of Hamburg’s ancient canals

alle Kapitel sehen