INTRODUCTION (continuation)

Such were a few of the Merchant Adventurers, and if I have treated them rather as a corporation than as individuals, it is not that I forget that they were men as well as merchants. But their chief significance to us is that they organised themselves on national lines to do battle with the German merchant, and carried the commercial war into Flanders and Brabant, into High Germany, into the Baltic, to Iceland, and even into Russia, the jealously guarded trade preserves of the German Hanse. These Merchant Adventurers were from their very nature and purpose in conflict with the Germans: they existed to challenge the supremacy of the League, for they were leagued together to carry English cloth overseas in their own ships and sell it in the mart towns of the Continent. In this they differed from the Merchants of the Staple, who shared their franchises with foreigners and were content to sell our raw material to the Flemish weaver.

But among all these English merchants I give the palm to Thomas Gresham. And his chief title to greatness was not that he founded Gresham College or the Royal Exchange, but that he "practised" with King Edward VI and "my Lord of Northumberland" to break the power of the German merchant in London. The problem before Gresham and his English contemporaries was to induce the Government to resume those privileges which placed the German in a position more favourable than the Englishman in other words, to secure a reform of the tariff. But the German was strongly entrenched, not only because he had great allies on the Continent, not only because his "scraps of paper" had the sanction of authority and antiquity, but for a more important reason. The Steelyard, as Anderson puts it, served as a sort of bank for the English kings. The English Government was in a chronic state of indebtedness to the German cities, and to destroy the influence of the German it was necessary to secure the financial independence of the Monarchy. And so it came about that in the time of Edward VI and Elizabeth we find Gresham employing all means to induce his fellow-merchants to lend money to the Crown. Thus, for example, old Stow tells us in his Survey of London: "King Edward VI borrowed money of Anthony Fugger and his nephews, who were vastly rich German merchants and bankers of Antwerp. And the city was bound with the King for payment. As I find, anno 1551 in the month of April, a recognisance made from the King to Sir Andrew Jud, Lord Maior of the City, and the Commonalty of the same, that the King shall discharge them, their successors, lands, possessions, and goods whatsoever, as well beyond the sea as on this side, from payment of certain sums of money Flemish, which they stood bound for to the said Anthony Fugger and his nephews to be paid at Antwerp." And Stow goes on to tell how Queen Elizabeth "thought of laying aside this custom of taking up money from foreign merchants and bankers, and concluded it better to borrow of her own subjects. . . . This counsel, that famous citizen, Sir Thomas Gresham, her agent, gave her." According to the same authority, Gresham had great difficulty in inducing the Merchant Adventurers "to borrow for the Queen." Not until the Secretary of the Queens Council (probably Cecil) "wrote to the Merchants to complain of their behaviour" did they lend the Queen money. This transaction of November and December 1569 was made the more necessary because "Duke d'Alva" had closed Antwerp to English trade. Now Stow states as the reason for this change in royal policy "that her own subjects might have the benefit of the interest of the money so lent her rather than strangers" --a very good reason as far as it goes; but we know from Gresham's letter to Queen Elizabeth, which I quote elsewhere,*) that Gresham’s real object was that the Queen should have no temptation to restore the "usurped privileges" of the Hanseatic League.

*) The letter will be found among the Appendices to Burgon's Life of Gresham.

Besides lending the Crown money, Gresham "practised against" the Germans in the Courts of Law. I have devoted a whole chapter to the once famous, but long-forgotten, suit of 1551, in which a stout jury of Merchant Adventurers found that the Germans had forfeited their privileges by "colouring" the goods of certain "sledded Polacks." *) It was a curious verdict, for the jury found as part of its true bill that English merchants should have a substantial preference over all foreign merchants, not native," in the English customs. In other words, the verdict was founded upon sound Protectionist principles. Needless to say, the Germans were shocked at such a court and such a finding "contrary to laws divine and human and the statutes of this realm and the express words of their ancient privileges." Yet it happened that there were no Germans at that time on the Privy Council, and when the appeal was heard before that august tribunal, it was unanimously decided that substantial justice had been done.

*) "He smote the sledded Polacks on the ice." Hamlet.

It might have been more heroic if the Germans had been defeated in battle rather than by loans and a suit at law, but it is characteristic of this strange and obscure struggle that the mortal blow should have come in this way. For the blow was mortal. It is true that "bloody Mary," as part of the marriage settlement with Philip, restored, or endeavoured to restore, the German privileges, but Gresham continued to "practise" with the Privy Council, and the German power in England remained effectually broken.

It was for Queen Elizabeth to carry the war into the enemy's country, and for her merchants to fight the Germans in their own markets of Stade, Emden, and Hamburg. I have already told the readers of the National Review the story of the last stage of this great conflict, how the Germans supplied Philip with money, munitions, sailors, soldiers, and even ships for his Armada, and how sixty Hanseatic hulks loaded with contraband were captured at one fell swoop by Drake in the Tagus. And yet even at this final and desperate climax of the struggle, Germany and England did not come to open blows, but fought each other with tariffs and trade interdicts. The expulsion of the Germans from their Steelyard in 1599 was but the final checkmate in a long game of expulsions, embargoes, tariff wars, and excommunications of which my last chapter gives an all too inadequate sketch.

I have hopes, nevertheless, that my story is neither sordid nor dull. If fighting is wanted, I can produce sea-battles and the sack of cities to prove that German and Englishman were far enough from living at peace in the Middle Ages. The German methods were then as now: they sank our harmless merchantmen and drowned our poor fisherfolk. In the time of Richard II, and again in the time of Henry III, there was even open war between England and the German cities. And why is Wenyngton forgotten, that stout man of Devon, who, with an inferior force, attacked the Lübeck fleet and brought it triumphantly into the Solent? Most of these battles between English and German merchants and sailors have been condemned by the lofty historian as mere acts of piracy unworthy of chronicle, yet they were part, heroic if obscure, of the long and stern fight waged by Englishmen for economic liberty. And Willoughby and Chancellor also I may justly call heroes, who circumnavigated the North Cape to circumvent the German and his ally the Spaniard. Willoughby, who died in a desolate harbour of Lapland, and Chancellor, who secured our first alliance with Russia, are worthy of something more than a grudging remembrance. And if we seek the heroic, I boast at least two figures as illustrious as any in our history, the first and the last of the barons, the soldier-statesman Simon de Montfort and the sailor-statesman Warwick the King-Maker. They both died by German conspiracy, and they were both remembered as heroes and patriots by their fellow-Englishmen.

And yet I am willing to concede that the English protagonists in this struggle were generally men more of brain than of brawn. Warwick, certainly, if not Leicester also, was greater as a statesman than as a warrior; Gresham won his victories by "practising” and so did his good ally, Burghley, the first and by a long way the greatest of the Cecils. His descendant, Lord Robert Cecil, is now in the Foreign Office. If he reads this little book he will find, what he perhaps does not now realise, that his ancestor defeated the Germans by giving protection to the English trader. He might also learn from this story that the Elizabethans did not deal in half-measures. When they blockaded Flanders they did not relax the blockade to let Germany do its Christmas trade with Spain. They were whole-hearted in the struggle, and their design was for the wealth and strength as well as the honour of England.

I am conscious that there are many faults and omissions in this book, because it was written in haste and with an imperfect equipment of knowledge. I have drawn freely upon secondary authorities when they were available to this I make open confession; but I may add with a good conscience that, wherever possible, I have tested these authorities by their primary sources. I have found that Lappenberg is generally to be trusted where lying does not serve his country, but that Sartorius is a higher and more equitable court. Busch, like Lappenberg, takes the German side. Schanz is great, but only as an economist. Reinhold Pauli has the style and method of an illustrious historian.

Anderson is fair, like Sartorius. As for the primary sources, there is endless material in the great Hanse Recesse (the archives of the League), in Rymer's Fcedera, in the Venetian archives edited by Brown, and in our own State papers.

To those English students who may care to trip me up and pursue the subject farther than I have gone, let me say at once that they are sure to find many mistakes in this little book. But in extenuation, at least for my errors of omission, let me say that, if I had allowed myself to be tempted down all the seductive avenues and enchanted glades of this subject, I should never have got to the end of my journey. In particular I had to refuse to go far into the reigns of Richard II and Henry VIII, not because they would have yielded little, but because in my judgment, though important, they were not decisive. *)

*) In particular, I refused to allow myself to enter upon the relations of the Hanseatic League with Scotland, although I found evidence of the great influence of the German cities on Scottish history before the Union of the Crowns. Thus, for example, on 11th October 1297, a month after the battle of Stirling Bridge, Andrew de Moray and William Wallace," the leaders of the army of the realm of Scotland," wrote to "the Mayors and Commons of Lübeck and Hamburg" that their country had been "recovered by war from the power of the English." Why did the Scottish leaders write to these cities? Because the Hanse, for purposes of its own, was supplying them with arms, and probably financing them. Mr. Evan Barron, in his Scottish War of Independence (pp. 69, 70), quotes this letter, which is preserved in the archives of Lübeck, but fails to explain it. He would add to the value of a fascinating book if he went further into this connection. Scotland's Wool was probably carried in German ships to Flemish looms. Had the Germans a Kontor in Scotland? Stirling, at once the head of the navigable Forth and a central and commanding point on the road from North to South, would have suited the German merchant very well. Was Stirling the town of the Easterlings? Berwick had at one time a "Flemish" garrison. Why? The Cheviots, like the Ochills at Stirling, would be important to the Flemish weaver. And why did the German cities supply Wallace (and later Bruce) with arms? Was it merely in the way of trade, or was there the deeper motive of weakening England and getting Scotland into their power? These, like many other problems no less absorbing, "abide our question."

And here let me say a word in guidance as to nomenclature. The Germans in England are at various stages called "Men of the Emperor," "Easterlings," "Almains," "Flemings” and "Dutchmen"; the Hanseatic League is called the "Steads” the "Towns” the "Hansa," the "Hanse," the "mesne Hanse"; their Guildhall in London is called "Gildhalla Teutonicorum," the Steelyard, and the Stilliard. These various names have confused even such authorities as Lappenberg and the editor of the Acts of the Privy Council. The term "Hanse" was used of any company of merchants: the Merchant Adventurers in the time of Edward VI divided themselves into the "old Hanse" and the "new Hanse," and the index to the Acts of the Privy Council confuses a quarrel between these two with the greater conflict between the Steelyard Merchants and the Merchant Adventurers. As to Germany itself, it is usually called Almaigne, with many variations of spelling, and sometimes Dutchland. In theory the Bang of the Romans only became Emperor when he was crowned by the Pope; but in later practice at least the custom was more honoured in the breach than in the observance. I have not boggled over all these niceties, but have striven only to give a rough and living outline sketch of the relations between Englishmen and Germans in my period.

And I have set the limits of my period for this reason mainly, that they include the rise and the fall of the German power in England, and all the stages of the first great conflict between England and Germany for supremacy in trade. I hope the story of our first great struggle with the Germans may have its lessons for us who are engaged in the second. For in the first great struggle the Germans were beaten, and they were defeated because England organised herself for victory.

IAN D. COLVIN.

London, St. Georges Church, Hanover Square 1790

London, St. Georgs, Hanover Square

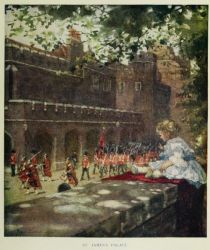

London, St. James Palace

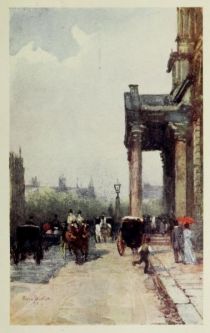

London, St. James Street from the New University Club

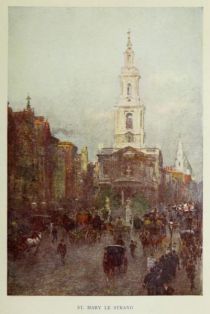

London, St. Mary le Strand

London, St. Mary Overy Kirche

London, St. Pauls from Hamstead Heath

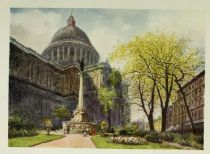

London, St. Pauls from the North-east Corner of the Churchyard

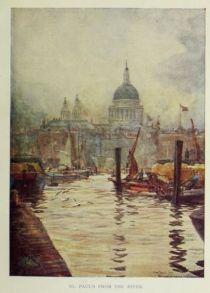

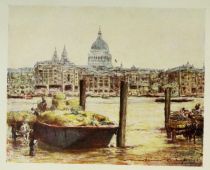

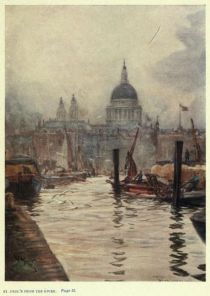

London, St. Pauls from the River

London, St. Pauls from the Surrey Side

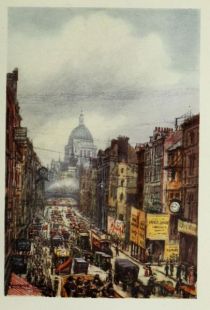

London, St. Pauls, Looking alon Fleet Street

London, St. Pauls von Fluss aus gesehen

London, Staple Inn

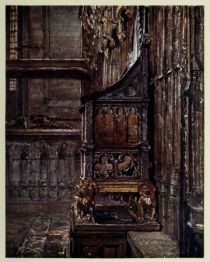

London, the Coronations Chair, Westminster Abbey

London, The Custom House and Billingsgate

London, the Dutch Garden, Kensington Palace

London, The Garden of Marlborough House

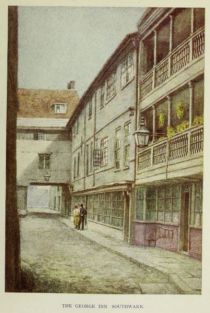

London, the George inn Southwark

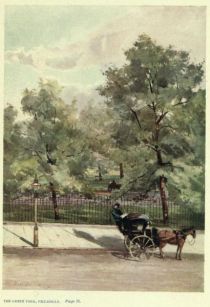

London, The Green Park, Piccadilly

London, the Green Park

London, The India Office

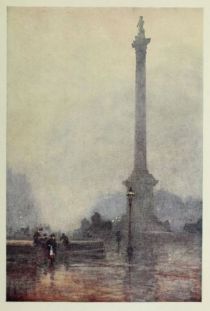

London, The Nelson Column on a Foggy Day

London, the Pavilion at Lords

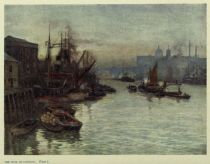

London, the Pool of London

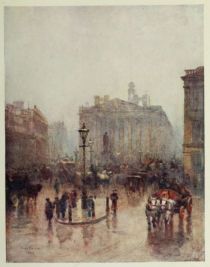

London, the Royal Exchange

London, the Serpentine

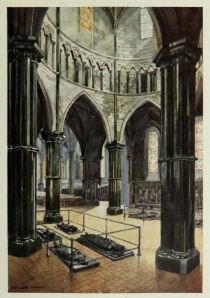

London, The Temple Church

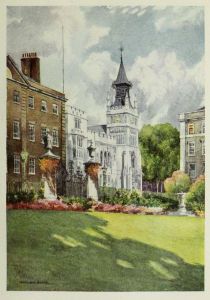

London, The Temple Garden

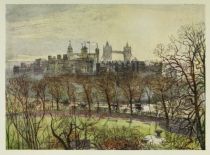

London, the Tower (2)

London, the Tower and Upper Pool

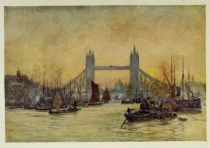

London, the Tower Bridge from Above Cherry Garden Pier

alle Kapitel sehen