X. Munich — a City of Good Nature.

Iam going to make Munich such an honor to Germany,“ declared Ludwig I, „that nobody will know Germany who has not seen Munich.“

This prophecy has not only been fulfilled, but fulfilled in such a natural, spontaneous way that the city is a running commentary on the character of its citizens. The capital of northern Germany is less an expression of its people than an embodiment of the character of its ruling family; but the Southern capital is an open book wherein even the stranger may read the popular love of beauty and of bohemian ways; the untranslatable Gemütlichkeit; the dislike of trade; the piety; the simple, reposeful breadth; the loyalty to superstition and romance; and the score of other qualities that go to make up the true Münchener.

Munich is, in great part, a creation of the nine- teenth century. Yet when one sees how cleverly and how lovingly she has woven the new about whatever remains of the old, it is easy to understand why she has been Germany's artistic leader for the last hundred years, and why such men of genius as Lenbach, von Ulide, Schwanthaler, Orlando di Lasso, and Richard Strauss have felt at home there.

My first impression of Munich was of a place sim-ply irradiated with the love of beauty. The principal streets, old and new, seemed as exquisitely calculated for effects of vista as the streets of Danzig; the squares, with their old tower-gates and churches and massed houses, were grouped as if composed by the eye of a painter. And although one half of the Marien-Platz is the work of our day, yet few squares in Europe have given me a deeper sense of the combined opulence and simplicity, the dignity and pure beauty, that used to invest the fonmis of medieval towns like Siena and Nuremberg.

In the Pinakothek I found a gallery of old paintings second to no other in the land but that of Dresden, and quite as strong in the Germanic schools as Dresden is in the Italian. Here one has an illumi- nating oversight of early Rhenish and Netherlandish art, and how it led, on the one hand, to such master- pieces as the elder Holbein's „St. Sebastian“ and Dürer's „Four Temperaments“; and, on the other hand, to canvases like Hals's inimitable little portrait of Willem Croes, Rembrandt's „Descent from the Cross,“ and the huge collection of Rubens, that Dionysus among painters. This gallery also surpasses Dresden's in the works of Murillo and of Titian, whose „Christ Crowned with Thorns“ is one of his richest canvases, both in its sensuous and its spiritual appeal. Indeed, Fritz von Uhde said once to me that, in his opinion, this was the greatest picture ever painted. The building itself has served for generations as a type of the ideal home for pictures. The New Pinakothek, a companion structure, holds a representative assemblage of modern German paintings, while the Schack Gallery has an unequaled collection of Bocklin and of Schwind, that Grimm of the easel who fixed on canvas the very essence of medieval romance and fairylore. In the fascinating new National Museum I found a vivid resume of the complete artistic history of the Bavarians, a collection unrivaled in its setting, and rivaled alone in its content by the Germanic Museum at Nuremberg. It was typical of the place that a whole floor should be given over to those tender, miniature representations of the Nativity which the Germans call Krippen. The Glyptothek holds an assemblage of masterpieces of Greek sculpture the equal of which cannot be found short of Rome or Paris. This is the home of the Barberini Faun, the Rondanini Medusa, and the famous pediment groups from Egina.

But despite all these signs of a rare artistic culture, it is plain that the Münchener has one passion passing his devotion to painting, sculpture, and architecture: he is at heart a child of the open air, and might sincerely say with Landor,

Nature I lov'd, and next to Nature, Art.

Through and through he is a devotee of those enchanted mountains the snow-capped summits of which lend the finishing touch to a distant view of his city; and toward whose forests and gem-like lakes he instinctively turns with Rucksack and staff whenever his work is done. In those leagues of grove and stream called the English Garden; in the blooming wood-ways along the riverside; and in the flashes of turf and blossom and foliage that punctuate his city the Miinchener seems forever proclaiming.

My heart 's in the highlands.

And indeed the city's bracing, eager mountain air — blowing two thousand feet above the sea — is largely accountable for the heaven-sent Munich temperament. This climate makes optimists as readily as that of Berlin makes pessimists.

There are hereditary reasons for the Müncheners' love of nature. For until recently a majority of the population had peasant blood in their veins. The North Germans are constantly reproaching them for their origin; but to a foreigner this strain of rustic naturalness and simplicity, found in the third largest city in the land, is one of its chief charms.

The Münchener does not go about trying to look impressive like so many other Germans, but is as natural as a lumberman or farmer. The city is so unconventional that a stranger must be very dull or very tongue-tied who feels lonely there. Any one may talk to almost any one, and a mixed crowd at a restaurant table is soon chatting with the ease of a group of old friends.

Few other places are so democratic. In the great beer-halls where Munich spends many of its leisure moments, one man is exactly as good as another. There you will find a mayor and an army captain rubbing shoulders with a sweep and a peddler, and all talking and laughing together with no sense of constraint. I like to recall a fragment of democracy that I met with on the platform of a trolley-car. There were five of us, repesenting almost as many grades of society. To us entered the conductor, saluted, and reached into his pocket. I supposed he was feeling for his bundle of transfers. Instead, he pulled forth a tortoise-shell snuif-box and handed it round. My fellow-passengers took their pinches with much good feeling. Then the conductor fixed us each in turn with the kindliest eyes in the world, and dusted his ruddy nose with a bandana equally ruddy.

Another incident was quite as characteristic. We were audibly admiring a picture of Carmen Sylva in a window. An old public porter, lounging near by, pricked up his ears. „What,“ he cried, '”she beautiful? You just ought to see my Gretchen!“ And he launched into an enthusiastic description of his wife and her charms of face, figure, mind, and heart.

Such whole-souled democracy would be impossible without the famous Gemütlichkeit of Munich. It is a misfortune that the English has no equivalent for this useful and eloquent word. Perhaps the lack is also significant. It means a sort of chronic goodwill-toward-men attitude, tinged with democracy and bubbling humor, with mountain air, and a large sympathy for the other fellow's point of view. Even Martin Luther called these people „friendly and good-hearted,“ and declared that if he might travel, he would rather wander through Swabia and Bavaria than anywhere else. And this, although these stanch Catholics hated the Reformer like the pest, and to this day still libel him by telling how he stopped at a tavern in the Sendlinger-Strasse and ran away without paying for his sausage.

The Müncheners are quite Austrian in the heartiness of their salutations. „Grüss di Gott!“ („God greet thee!“) friends exclaim on meeting; and „B'hüt di Gott!“ („God keep thee!“) at parting. When a crowd, in breaking up, coos a general Adje, it is as though they had broken forth into a chorus of gentle song. „One almost has to say good-by to the trees here,“ a Chicago girl once declared.

The Müncheners are so good-natured that they hate to trouble one for their, just dues. I have had more than one landlady who could hardly be induced to present her bill, and even then half the extras were not included. On a certain street-car line I was never approached for fare during four consecutive rides. And yet — strange paradox — Munich, is the gateway of greedy Italy, and its people have many marked Italian characteristics.

They have in their Gemütlichkeit a humorous streak capable of saving almost any situation. „Dawn breaks after the blackness of night,“ exclaimed the servant, with an engaging smile, as she brought in my omelet forty minutes late.

Thus equipped, they can extract pleasure from anything — even from the new annex to the imposing court of justice. This annex is gaudy with enameled tiles, and makes a violent discord with the older, baroque building, A story is current of a condemned murderer who was allowed a last wish.

„Kindly lead me past the new court of justice,“ he answered, „that I may have one more good laugh before I die.“

Twice a year all the exuberant, bohemian qualities of the people find full outlet. The October Festival is held on the Theresien Wiese, near Schwanthaler's colossal statue of Bavaria, and, on a large scale, is a cross between an American circus and a French fete. The Karneval is the most festive season in the calendar. Twice a week from Twelfth Night to Ash Wednesday there are masked balls in which nearly every one joins. During Karneval, all necessity“ for introductions in a public place is set aside, and no man may insist on monopolizing his partner. The last three days are called Fasching, and then the fun grows fast and furious. General license reigns indoors and out. For seventy-two hours there is little thought of sleep. The streets are alive with masks and costumes, with confetti and paper serpents. Any masked lady may be kissed with impunity, and few are unmasked. It is a scene even more hilarious and brilliant than that other carnevale which seethes up and down the Roman Corso. And this festival seems to come more directly „out of the abundance of the heart“ than the Italian one. There it has a marked theatrical quality. Here it is a sincere, hearty, intimate expression of the brotherhood of man, the sisterhood of woman.

This intimate quality, found even amid the madness of Karneval, is one of the things that endear the city most to those who know it. In absence one yearns for certain Munich sights as for the sight of tried and trusted friends.

The Old Rathaus, for instance, has a specially intimate appeal, with its noble tower-gate and its simple, beautiful hall enlivened by the Gothic humor of Grasser's dancing figures. One has much the same feeling for the great, homely tower of St. Peter's („The Old Peter,“ in the vernacular), whence on Saturday evenings and Sunday mornings a trombone quartet breathes mellow chorales; for the little Church of St. John, built next their own fanciful house, and presented to Munich by those renowned artists, the Asam brothers, who poured out on its walls so much native buoyancy and humor; for the toy houses of the village-like Au, clustering along their brook; for the dear old St. Jacobs-Platz; and perhaps most of all for the gigantic body and thick, dusty-red towers of the Church of Our Lady, like a portly, genial, confiding burgher, ready to welcome you into his heart on the slightest provocation.

Artists, as a rule, detest commerce, and these artistic people have had to make trade as attractive as possible for themselves. Hence they have chosen to deal in the two things they like best, art and beer.

Munich is not only the center of the arts and crafts movement, of the photographic, lithographic, and allied industries, but also, owing to its honesty and its situation in the center of Europe, it is the best place to buy „antiquities.“ There is even one commercial institution which the Müncheners actually contrive to invest with their carnival spirit. The Dult is a biennial rag-fair, covering many acres near the toy houses of the Au. Here, amid the booths that hold the Bavarian junk harvest of the last six months, the eye of the enthusiast may discover Egyptian and Roman bronzes, fine old laces and embroidered vestments, Sicilian terra-cottas, Renaissance furniture and ironwork, Russian brasses, even precious prints and paintings, enamels and jewels, going for a mere song. The knowing disguise themselves in rags in order to buy cheaper. All one's friends are there, and when any one makes a lucky find, all the rest join his impromptu carnival of triumph at the Citizens' Brewery hard by.

Munich brews more and better beer than any other city. It is hard to realize what an integral part of the place and its people this liquid is, and what a deep sentiment they have for it. I once overheard a short dialogue entirely characteristic of the local point of view:

Waitress: „Yet another beer?“

Citizen: „What a question!“

„The Bavarian can put up with anything,“ runs a well-known proverb, „even with the fires of purgatory, if only he can have his beer.“ It flows in his veins; and one is sometimes tempted to call what flows beneath the beautiful bridges „the Isarbrau.“

The saying goes that those landmarks, the twin towers of the Church of Our Lady, are capped by two great beer-mugs. And the city's symbol is the far-famed Miinchener Kindl — a boy in a monk's habit and often with a stein in his hand. Legend explains the figure by telling how our Saviour once came down, disguised as a little child, to bless the place and further the good works of the monks, who were the original local brewers. In this connection it is interesting to know that Cloister Schäftlarn, the germ of Munich, still turns out an excellent brew.

For many centuries the quality of Munich beer has been jealously guarded by law. There is an amusing rhymed legend about the methods of inspection. Three chosen councilors went to the brewery, but instead of pouring the beer down their throats, they poured it upon a bench, sat down together, then rose, said started for the door. If the bench accompanied them all the way, then the beer was strong and good. „But in these degenerate days,“ wails the chronicler, „far from having the bench stick to them, they stick, instead, to the bench!“

A marked trait of this hearty people is their devotion to the ancient line of Wittelsbach. In temperament many of the dukes and kings of Bavaria have shown themselves true Müncheners, specially in their love of beauty; and while, in many cases, their architectural taste has not fully expressed the character of the people, yet, from the first ducal castle down to the National Museum and the new bridges, the Wittelsbachs have filled the centuries with architecture which is, on the whole, racy of the soil, though many of the buildings are in the styles of distant ages and nations.

These Wittelsbachs have been closer to their people than most ruling houses, and some of them have been loved in return as kindred spirits. It is touching to remember how they would call out to Max Joseph as he rode past in troublous times: „Weil du nur da bist, Maxl, ist alles gut.“ („Seeing you 're here, Many, everything 's all right.“) On the abdication of their Maecenas, Ludwig I, they brought the old man to tears with their wild demonstrations of affection; and aged citizens have told me that heartbreaking scenes were witnessed when it became known that mad Ludwig II had taken his own life.

The earlier Wittelsbach architecture is more in harmony with Munich character than is the later. There is the romantic „Old Court,“ on the site of the first ducal castle, with its Gothic portals and façades, its picturesque, dunce-capped oriel window, and the quaint fountain murmuring in the center.

Near by, from a lane behind the post-office, one comes suddenly upon the old Tourney Court, now called the Court of the Mint. It is a typical work of the German Renaissance. The oblong space is surrounded by three tiers of colonnades, and the squat, dusky-red pillars and flattened arches breathe the ponderous Gemutlichheit of the days when Munich used to applaud the flower of Bavarian nobility breaking lances in the lists below, the pavement of which is now littered with the charcoal and the crucibles of the royal mint.

About the palace itself there hangs little of the atmosphere of olden days. For each ruler of the long line felt it his duty to add to, subtract from, multiply, and divide this huge complex, until the medieval was almost eliminated, and many of the later portions became unimpassioned echoes of French or Italian prototypes. For all this, there are a few parts of the palace that delightfully reflect the Miinchener. „Wherever the garment of foreign style did not quite come together,“ as Weese quaintly says, „the honest German skin peeped through.“

In the long, formal sweep of the western façade, for example, a bronze Madonna stands in a niche above an ever-glowing light, a tender German motif borrowed from the highland farmhouse, with its wooden patron saint.

In the Grotto Court one comes suddenly on a delightful instance of Bavarian charm — a vivid fleck of soft turf full of water-babies on ivied pedestals surrounding a fountain of Perseus worthy of the streets of old Augsburg. The plashing of the water, the cool greens and yellows of the palace walls, the perfect patina of the sculptures, the fantastic shell grotto at one end — all make a pleasant contrast to the monotonous splendors of the long festal suites within.

In the Fountain Court there is less of dreamy charm and more of the carnival spirit. On a jolly rococo pedestal of mossed stone poses Otto the Great, with his eye on the crowd of frivolous water deities below, among whom are the genii of the four rollicking rivers of Bavaria. They have that lovely iridescence which seems to thrive best on the bronzes of Munich, and which is specially brilliant on the Little Red Riding-Hood fountain in the Platzl.

The archway leading to the Chapel Court contains some reminders of the good old days. Chained to the earth is a black stone weighing about four hundred pounds. A rhymed inscription relates how, in the year 1490, Duke Christopher picked it up and „hurled it far without injuring himself.“ This is the same hero who, at the corner of the Marien-Platz called Wurmeck, killed a dragon that was terrorizing the town. It seems that the good duke was in love with a beautiful and popular daughter of the people, and that he agreed with his two rival suitors to hold a sort of field-day and let the best man win the maiden. The first event was putting the stone, and Christopher won. The second was hitch-kicking, and three nails in the wall immortalize the three astonishing records. The inscription proceeds:

Drey Nägel stecken hie vor Augen,

Die mag ein jeder Springer schaugen,

Der höchste zwölf Schuech vun der Erdt,

Den Herzog Christoph Ehrenwerth

Mit seinem Fuess herab that schlagen.

Kunrath luef bis zum ander' Nagel,

Wol vo' der Erdt zehnthalb Schuech,

Neunthalben Philipp Springer luef,

Zum dritten Nagel an der Wandt.

Wer höher springt, wird auch bekannt.

(Before your eyes protrude nails three

Which every jumper ought to see.

The highest, twelve shoes from the earth,

Duke Christopher, a man of worth,

Kicked from its proud position there.

Conrad leaped up into the air

Unto the second — ten shoes steep.

Unto the third — Phil Springer's leap —

Was nine and a half shoes from the ground.

Who higher leaps will be renowned. )

The poet Görres concludes a lyric on this event with the apposite wish:

Und möge unsern Fürsten all

Der liebe Gott verleihn

Aus jeder Noth den rechten Sprung

Und Kraft für jeden Stein.

(And may the dear Lord to each one

Of all our rulers loan

Skill to leap out of every ill

And strength for every stone.)

Where mthin palace gates is to be found a more striking memorial of good-fellowship between ruler and subject?

In its ground-plan, in its monumental façades and its long flights of festal cliambers, the palace shows a simple, reposeful breadth that is characteristic of the city and its people. It is the sort of breadth that one looks for in the work of great artists. And one imagines that there has entered into the Münchener something of the generous, free spirit of his marbles from Ægina, of his Titian canvases, and of the calm strength of his hills.

He is built on large, deliberate lines— a person not to be hurried or crowded. His speech is broad and slow, and even his graves are set unusually far from one another.

This large quality is specially marked in Munich's four monumental streets. The Brienner-Strasse takes its stately way from the portal of the Royal Gardens to the Königs-Platz, a square the simple majesty of which might suggest the Athenian Acropolis. In front is the Doric dignity of the Propylæa, erected to celebrate in advance Bavaria's ill-fated attempt to shake Greece free of Turkey. On each hand are Ionic and Corinthian temples, devoted respectively to sculpture and the Secessionist school of painting. Between these serene, broadly modeled buildings lie only stretches of turf and roadway.

The great simplicity of such a scene is exaggerated in the Ludwig-Strasse into monotonous austerity, especially where the hard Roman Arch of Triumph, the cloister-like university, the Ludwig Church, and the public buildings line up their dreary façades. But, in spite of these, it is an imposing street. It shows at its best when the sun of early afternoon slants down to correct its horizontal lines, or when, at sunset, every homely westward road becomes a flaming way to some enchanted castle, and, behind the Hall of Generals, the tower of the New Rathaus changes in the glow to a tower of quicksilver. The southern end of the Ludwig-Strasse is most delightful at noon, when the military band plays and the gay crowd comes to promenade and see the Royal Guard relieved.

These newer parts of Munich have been called the Wittelsbachs' note-book of travel, where they have recorded in stone and bronze their deepest impressions of other lands. In the Königs-Platz they wrote down their love of Greece, and their love of Italy in the Odeons-Platz.

The Hall of Generals is a copy of the Florentine Loggia dei Lanzi; the church of the Theatines on the right was modeled after the Church of S. Andrea della Valle in Rome; on the left, the western f a9ade of the palace is typically Italian, while the southern was actually copied from the Pitti Palace. The very pigeons graciously peck corn from the palms of American tourists in the accepted Venetian manner. One sees over the foliage of the Royal Garden the iridescence of the Army Museum's dome and the lordly tower of St. Anna's, and involuntarily glances about, wondering why there are no dark-skinned folk sipping their wine on the sidewalk; why no forms in roseate rags lie asleep on the steps of the loggia, and why no melting voice and prehensile fingers are touching one's heart and sleeve for ”un soldo!“

Though the Maximihans-Strasse is unfortunate architecturally, yet there is the same grand manner in its round-arched buildings, and something nobly commanding in the way the Maximilianeum dominates the city from among the gardens across the Isar.

With its splendid new home for Wagnerian musicdrama and its National Museum, the modern Prinzregenten-Strasse, laid out by some inspiration in a gentle, medieval curve, shows that the city is not lagging behind her traditions.

The best exemplar of this quality of reposeful breadth, the Church of Our Lady, is exemplar also of another leading trait of Munich — her deep relig- ious spirit. In fact, these simple, massive walls, adorned outside and in with quaint and beautiful carvings and paintings, seem to epitomize the whole Miinchener. Some of the tombstones, like that of the blind musician, are even suffused with a kindly humor; and around the mausoleum of Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian, a worthy companion piece to Maximilian's tomb at Innsbruck, one may see the love these warm-hearted people still bear to one who made Munich's fortunes his own. Among the many legends that cluster here is one of this emperor, who was found, centuries after his death, in the crypt under the mausoleum, sitting upright on his throne, as Charlemagne is said to have been found at Aix-la- Chapelle.

There is a black footprint on the pavement under the organ-loft at a place where a curious architectural trick has made all the windows invisible. There one is told how the builder of the church made a compact with the devil, who agreed to help him on condition that God's sunlight should be kept out of the building. The devil saw the windows growing, and was glad. „Come along with me,“ said he to the builder. „Come along yourself,“ cried the builder, and led him under the choir-loft. The devil looked in vain for a window, stamped his foot in impotent rage, and vanished. But his footprint has remained to this day.

The builder of St. Michael's was less fortunate, for when he had completed the bold barrel-vaulting that spans the most noteworthy of German Renaissance halls, it is said that he cast himself from the roof in despair, fearing that his work would not stand. This majestic church was built by the Jesuits to celebrate the coming triumph of the Counter-Reformation. It was an eloquent prophecy of Munich's present Roman Catholic solidarity.

St. Peter's is the oldest local church, and contains the choicest tombstones; but the interior has suffered shockingly from the vandals of baroque times.

These older examples of the Munich churches well represent the broad, simple, reposeful characteristics of the place. Certain younger ones, however, like All Saints', Trinity, St. John's, and the Church of the Jesuits, fairly sparkle, in their baroque and rococo finery, with the carnival spirit.

The most noteworthy modern churches are the Court Church, a little Byzantine pearl of a place that transports one in a breath to the atmosphere of the Cappella Palatina at Palermo; and the Basilica of St. Boniface, Ludwig's record of his most precious hours in Ravenna and Rome. But, of all the later churches, St. Anna's is my favorite. Built of rough coquina, its picturesque complex of gables, turrets, and spires grouped about the central tower is already finely weathered. The broad, walled terrace, the moated fountain borne on pillars, the deeply felt modeling of the façade, the portal worthy of some great medieval builder — all these blend in an ensemble the equal of which I have not seen elsewhere in modern Romanesque architecture.

All these churches are real places of worship. One finds there the same spirit of fervor that one expects to find in Tyrol or Italy. And this is natural, for the city grew out of a religious institution near by, and its very name — Ad Monachos, or „At the Monks“ — stamps it as the child of Cloister Schäftlarn. The whole daily walk and conversation of the people is connected in some way with ecclesiasticism. They say of anything that moves rapidly: „It runs like a paternoster“; of a heavy drinker, „He guzzles like a Knight Templar.“ A mild state of intoxication is called a Jesuitenräuschlein; while an unfortunate in the advanced stages is „as drunk as a Capuchin father.“

In Catholic communities farther north there is a strain of cooler intellectuality in the devotions of the people. Here all is emotion. In fact, until recently this lack of balance has had a grievous effect on Munich's intellectual life, which can boast few writers of note. But it has, on the other hand, kept a warm place in the hearts of the people for romantic legends and superstitions. The Münchener has clung so much more successfully to these beliefs than to his medieval buildings that the place gives the illusion of having more atmosphere than its architecture would warrant.

The folk still call Tuesday and Thursday by the ancient names, Irtag ( day of the war-god Ares ) and Pfinztag, from the Greek for Fifth Day.

On Twelfth Night they cast evil spirits out of their homes with a ceremony descended in substance directly from the heathen rites of Odin. They move from room to room, sprinkling the powder of sacred herbs on a shovelful of live coals, and write up over every door with consecrated chalk the mystic initials †C †M †B. These letters stand for the three Wise Men of the East, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar.

This is of a piece with the conservative instinct that still continues the Passion Play in the neighboring village of Oberammergau.

With their Bavarian zest m anecdote, the people love to tell of a basilisk which lived in a well on the Schrammer-Gasse opposite the present bureau of police. The glance of this medieval Medusa killed all who looked at it, until some German Perseus held a mirror over the well and let the creature slay itself.

The local belief in witches and black art is wonder- fully persistent. Tales are still current of spirits who took the form of black calves and could be out- witted only by being banned into a tin bottle with a screw-top. There is the legend of an unprincipled lawyer who died and was laid out in the usual way with crucifix and candles. All at once two black ravens appeared at the window, broke the pane with their beaks, and flew away again with a third raven which suddenly appeared from within the chamber of death. The candles were quenched in a trice, the crucifix overturned, and the lawyer's corpse turned as black as night.

Then there is the favorite story of Diez von Swinburg, a robber knight who, with four of his men, was caught and condemned to death. Diez begged in vain for the lives of his comrades. Finally he cried: „Will you, then, spare as many as I run past after I have been beheaded?“ With contemptuous laughter the request was granted.

Diez placed his men in a line, eight feet apart, with those he loved best nearest him. Well pleased, he knelt down. His head fell. Then he rose, turned, ran stumbling past all of his followers, and collapsed in a heap.

People who cherish such beliefs do not easily give up time-honored customs, and Munich is still rich in romantic rites. During the plague of 1517, when half the city lay dead and the other half was stricken with despair, the Gild of Coopers gave every one fresh heart by organizing an impromptu carnival of dance and song in those terrible streets. Once every seven years, in honor of this act, the Schäffler Tanz, or Coopers' Dance, still takes place, the coopers dancing in their ancient garb — green caps, red satin doublets, long white hose — and carrying half-hoops bound with evergreen.

Sad to say, the picturesque Metzgersprung, or Butchers' Leap, has been recently done away. After a jolly round of dancing and parades and a service in „The Old Peter,“ the Butchers' Gild would meet around the Fish Fountain in the Marien-Platz and, after elaborate ceremonies, the graduating apprentices, dressed in calfskins, would leap into the basin and thus be baptized as full-fledged butchers.

In this same beloved square the pick of all Munich, old and young, joins in the Corpus Christi procession, which, gay with students' caps and banners and guild-insignia, winds from the Church of Our Lady and groups its rainbow colors around the old Pillar of Mary, where the archbishop, who has been preceded by white-robed maidens with flowers and candles, reads the Scriptures.

Despite its worship of the past, however, Munich is, on the whole, a progressive city. Its recent commercial strides have been astonishing. For a century it has led Germany in artistic matters. And that it still leads, is shown by its annual exhibitions of painting and sculpture, of arts and crafts, and by such architecture as the National Museum, St. Anna's, the building of the „Allgemeine Zeitung,“ and some of the new school-houses.

The Isar Valley, Schleissheim, and Nymphenburg belong even more intimately to Munich than the Havel and Potsdam belong to Berlin. To wander through the fragrant woods and by the castles and quaint villages of the Isar gorge is to hear and see the Münchener at his best. For he is always taking a few hours off there, and is always laughing and singing and yodeling. It seems as though the happy creature cannot turn his face away from town and swing into stride without breaking into one of his hearty songs.

The castle of Schleissheim was built, like St. Michael's and the Propylsea, to celebrate a future triumph. For Max Emanuel imagined that he was going to be elected emperor, and could not restrain his exuberance at the thought. Those splendid baroque halls never held his imperial court, for he was driven into exile before they were finished; but they hold to-day one of the foremost Bavarian collections of paintings, especially rich in the old German school. The formal gardens, with their statues, vases, and tree-fringed waters, contrast pleasantly with the severe facades of the castle, and form a sort of prelude to the more generous scale of Nymphenburg, the most lovable of all the many German paraphrases of Versailles.

My first visit to Nymphenburg was on a perfect afternoon in late summer. I came into a circle of buildings almost a mile in circumference, a barren, baroque circle inclosing a cheerless waste full of ugly canals and ponds, where the lords and ladies of the eighteenth century, in their gondolas, used to ape the water fetes of France and Italy. There is all too little of the festal spirit left there now.

But on the other side of the castle the atmosphere changed like magic. I plunged into a brilliant Versailles, but a sweeter, more gemütlich one than any of my acquaintance— a vast garden that knew how to be at once formal and natural. There was a wide sweep of lawn where old women and bullocks and rustic wains were busied with haycocks among long rows of marble deities and urns. In the middle of the scene a fountain flashed high in the sunlight, falling among rough rocks. Humorous lines of Noah's Ark evergreens stood attention. In the distance, beyond a linden-flanked canal, were waterfalls; and one caught a glimpse of the misty horizon. Right and left, narrower lanes of foliage opened vistas of water-flecked lawns checkered with patches of sunlight. Far away gleamed little pools, as bright as pools of molten steel, and near one of them I came upon a dream of a summer-house called the Amalienburg, one of the most delicate and radiant bits of rococo fantasy in the German land.

Munich is so diffuse a city that it is hard to think of it as a unit until one has seen it from some high place. It was a revelation to me when I climbed past the chimes of „The Old Peter“ to the town-pipers' balcony. There lay the city as flat as a lake. To the westward was a jumble of sharp, tiled roofs, turning the skylights of myriad studios searchingly toward heaven, as though the houses were all bespectacled professors. Beyond the eloquent front of St. Michael's rose the court of justice in all its dignity, with the humorous annex which the murderer begged to see. The Church of Our Lady towered over old Munich, symbol of the warm South-German heart. Immediately to the north rose that „mount of marble“ the New Rathaus, a, reminder of Milan cathedral, in its dazzling, restless opulence, and with a touch of the theatrical manner seen beside the quiet comeliness and reserve of the Old Rathaus. Beyond, the Pitti-like façade of the palace stood out against the soft leagues of the English Garden. Eastward the Maximilianeum's perforated front reposed like a well-kept ruin amid the luxuriance of its waterside park. The Isar, itself invisible, made a bright zone of green through the city; and in the south, crowning and glorifying the whole scene, the snow glistened on the far peaks of the Bavarian Highlands.

A party of students had come up, and were gazing with affectionate eyes on their city. Quite without warning they burst into a song which I shall always associate with that tower and its glorious panorama:

So lang die grüne Isar durch d' Münchnerstadt noch geht

So lang der alte Peter auf 'm Peter's-Platz noch steht,

So lang dort unt' am Platzl noch steht das Hofbräuhaus,

So lang stirbt die Gemütlichkeit in München gar net aus.

Freely rendered:

So long as through our Munich the Isar rushes green,

So long as on St. Peter's Place Old Peter still is seen,

So long as in the Platzl the Court-brew shall men nourish.

So long the glowing, kindly heart of Munich-town shall flourish.

This prophecy has not only been fulfilled, but fulfilled in such a natural, spontaneous way that the city is a running commentary on the character of its citizens. The capital of northern Germany is less an expression of its people than an embodiment of the character of its ruling family; but the Southern capital is an open book wherein even the stranger may read the popular love of beauty and of bohemian ways; the untranslatable Gemütlichkeit; the dislike of trade; the piety; the simple, reposeful breadth; the loyalty to superstition and romance; and the score of other qualities that go to make up the true Münchener.

Munich is, in great part, a creation of the nine- teenth century. Yet when one sees how cleverly and how lovingly she has woven the new about whatever remains of the old, it is easy to understand why she has been Germany's artistic leader for the last hundred years, and why such men of genius as Lenbach, von Ulide, Schwanthaler, Orlando di Lasso, and Richard Strauss have felt at home there.

My first impression of Munich was of a place sim-ply irradiated with the love of beauty. The principal streets, old and new, seemed as exquisitely calculated for effects of vista as the streets of Danzig; the squares, with their old tower-gates and churches and massed houses, were grouped as if composed by the eye of a painter. And although one half of the Marien-Platz is the work of our day, yet few squares in Europe have given me a deeper sense of the combined opulence and simplicity, the dignity and pure beauty, that used to invest the fonmis of medieval towns like Siena and Nuremberg.

In the Pinakothek I found a gallery of old paintings second to no other in the land but that of Dresden, and quite as strong in the Germanic schools as Dresden is in the Italian. Here one has an illumi- nating oversight of early Rhenish and Netherlandish art, and how it led, on the one hand, to such master- pieces as the elder Holbein's „St. Sebastian“ and Dürer's „Four Temperaments“; and, on the other hand, to canvases like Hals's inimitable little portrait of Willem Croes, Rembrandt's „Descent from the Cross,“ and the huge collection of Rubens, that Dionysus among painters. This gallery also surpasses Dresden's in the works of Murillo and of Titian, whose „Christ Crowned with Thorns“ is one of his richest canvases, both in its sensuous and its spiritual appeal. Indeed, Fritz von Uhde said once to me that, in his opinion, this was the greatest picture ever painted. The building itself has served for generations as a type of the ideal home for pictures. The New Pinakothek, a companion structure, holds a representative assemblage of modern German paintings, while the Schack Gallery has an unequaled collection of Bocklin and of Schwind, that Grimm of the easel who fixed on canvas the very essence of medieval romance and fairylore. In the fascinating new National Museum I found a vivid resume of the complete artistic history of the Bavarians, a collection unrivaled in its setting, and rivaled alone in its content by the Germanic Museum at Nuremberg. It was typical of the place that a whole floor should be given over to those tender, miniature representations of the Nativity which the Germans call Krippen. The Glyptothek holds an assemblage of masterpieces of Greek sculpture the equal of which cannot be found short of Rome or Paris. This is the home of the Barberini Faun, the Rondanini Medusa, and the famous pediment groups from Egina.

But despite all these signs of a rare artistic culture, it is plain that the Münchener has one passion passing his devotion to painting, sculpture, and architecture: he is at heart a child of the open air, and might sincerely say with Landor,

Nature I lov'd, and next to Nature, Art.

Through and through he is a devotee of those enchanted mountains the snow-capped summits of which lend the finishing touch to a distant view of his city; and toward whose forests and gem-like lakes he instinctively turns with Rucksack and staff whenever his work is done. In those leagues of grove and stream called the English Garden; in the blooming wood-ways along the riverside; and in the flashes of turf and blossom and foliage that punctuate his city the Miinchener seems forever proclaiming.

My heart 's in the highlands.

And indeed the city's bracing, eager mountain air — blowing two thousand feet above the sea — is largely accountable for the heaven-sent Munich temperament. This climate makes optimists as readily as that of Berlin makes pessimists.

There are hereditary reasons for the Müncheners' love of nature. For until recently a majority of the population had peasant blood in their veins. The North Germans are constantly reproaching them for their origin; but to a foreigner this strain of rustic naturalness and simplicity, found in the third largest city in the land, is one of its chief charms.

The Münchener does not go about trying to look impressive like so many other Germans, but is as natural as a lumberman or farmer. The city is so unconventional that a stranger must be very dull or very tongue-tied who feels lonely there. Any one may talk to almost any one, and a mixed crowd at a restaurant table is soon chatting with the ease of a group of old friends.

Few other places are so democratic. In the great beer-halls where Munich spends many of its leisure moments, one man is exactly as good as another. There you will find a mayor and an army captain rubbing shoulders with a sweep and a peddler, and all talking and laughing together with no sense of constraint. I like to recall a fragment of democracy that I met with on the platform of a trolley-car. There were five of us, repesenting almost as many grades of society. To us entered the conductor, saluted, and reached into his pocket. I supposed he was feeling for his bundle of transfers. Instead, he pulled forth a tortoise-shell snuif-box and handed it round. My fellow-passengers took their pinches with much good feeling. Then the conductor fixed us each in turn with the kindliest eyes in the world, and dusted his ruddy nose with a bandana equally ruddy.

Another incident was quite as characteristic. We were audibly admiring a picture of Carmen Sylva in a window. An old public porter, lounging near by, pricked up his ears. „What,“ he cried, '”she beautiful? You just ought to see my Gretchen!“ And he launched into an enthusiastic description of his wife and her charms of face, figure, mind, and heart.

Such whole-souled democracy would be impossible without the famous Gemütlichkeit of Munich. It is a misfortune that the English has no equivalent for this useful and eloquent word. Perhaps the lack is also significant. It means a sort of chronic goodwill-toward-men attitude, tinged with democracy and bubbling humor, with mountain air, and a large sympathy for the other fellow's point of view. Even Martin Luther called these people „friendly and good-hearted,“ and declared that if he might travel, he would rather wander through Swabia and Bavaria than anywhere else. And this, although these stanch Catholics hated the Reformer like the pest, and to this day still libel him by telling how he stopped at a tavern in the Sendlinger-Strasse and ran away without paying for his sausage.

The Müncheners are quite Austrian in the heartiness of their salutations. „Grüss di Gott!“ („God greet thee!“) friends exclaim on meeting; and „B'hüt di Gott!“ („God keep thee!“) at parting. When a crowd, in breaking up, coos a general Adje, it is as though they had broken forth into a chorus of gentle song. „One almost has to say good-by to the trees here,“ a Chicago girl once declared.

The Müncheners are so good-natured that they hate to trouble one for their, just dues. I have had more than one landlady who could hardly be induced to present her bill, and even then half the extras were not included. On a certain street-car line I was never approached for fare during four consecutive rides. And yet — strange paradox — Munich, is the gateway of greedy Italy, and its people have many marked Italian characteristics.

They have in their Gemütlichkeit a humorous streak capable of saving almost any situation. „Dawn breaks after the blackness of night,“ exclaimed the servant, with an engaging smile, as she brought in my omelet forty minutes late.

Thus equipped, they can extract pleasure from anything — even from the new annex to the imposing court of justice. This annex is gaudy with enameled tiles, and makes a violent discord with the older, baroque building, A story is current of a condemned murderer who was allowed a last wish.

„Kindly lead me past the new court of justice,“ he answered, „that I may have one more good laugh before I die.“

Twice a year all the exuberant, bohemian qualities of the people find full outlet. The October Festival is held on the Theresien Wiese, near Schwanthaler's colossal statue of Bavaria, and, on a large scale, is a cross between an American circus and a French fete. The Karneval is the most festive season in the calendar. Twice a week from Twelfth Night to Ash Wednesday there are masked balls in which nearly every one joins. During Karneval, all necessity“ for introductions in a public place is set aside, and no man may insist on monopolizing his partner. The last three days are called Fasching, and then the fun grows fast and furious. General license reigns indoors and out. For seventy-two hours there is little thought of sleep. The streets are alive with masks and costumes, with confetti and paper serpents. Any masked lady may be kissed with impunity, and few are unmasked. It is a scene even more hilarious and brilliant than that other carnevale which seethes up and down the Roman Corso. And this festival seems to come more directly „out of the abundance of the heart“ than the Italian one. There it has a marked theatrical quality. Here it is a sincere, hearty, intimate expression of the brotherhood of man, the sisterhood of woman.

This intimate quality, found even amid the madness of Karneval, is one of the things that endear the city most to those who know it. In absence one yearns for certain Munich sights as for the sight of tried and trusted friends.

The Old Rathaus, for instance, has a specially intimate appeal, with its noble tower-gate and its simple, beautiful hall enlivened by the Gothic humor of Grasser's dancing figures. One has much the same feeling for the great, homely tower of St. Peter's („The Old Peter,“ in the vernacular), whence on Saturday evenings and Sunday mornings a trombone quartet breathes mellow chorales; for the little Church of St. John, built next their own fanciful house, and presented to Munich by those renowned artists, the Asam brothers, who poured out on its walls so much native buoyancy and humor; for the toy houses of the village-like Au, clustering along their brook; for the dear old St. Jacobs-Platz; and perhaps most of all for the gigantic body and thick, dusty-red towers of the Church of Our Lady, like a portly, genial, confiding burgher, ready to welcome you into his heart on the slightest provocation.

Artists, as a rule, detest commerce, and these artistic people have had to make trade as attractive as possible for themselves. Hence they have chosen to deal in the two things they like best, art and beer.

Munich is not only the center of the arts and crafts movement, of the photographic, lithographic, and allied industries, but also, owing to its honesty and its situation in the center of Europe, it is the best place to buy „antiquities.“ There is even one commercial institution which the Müncheners actually contrive to invest with their carnival spirit. The Dult is a biennial rag-fair, covering many acres near the toy houses of the Au. Here, amid the booths that hold the Bavarian junk harvest of the last six months, the eye of the enthusiast may discover Egyptian and Roman bronzes, fine old laces and embroidered vestments, Sicilian terra-cottas, Renaissance furniture and ironwork, Russian brasses, even precious prints and paintings, enamels and jewels, going for a mere song. The knowing disguise themselves in rags in order to buy cheaper. All one's friends are there, and when any one makes a lucky find, all the rest join his impromptu carnival of triumph at the Citizens' Brewery hard by.

Munich brews more and better beer than any other city. It is hard to realize what an integral part of the place and its people this liquid is, and what a deep sentiment they have for it. I once overheard a short dialogue entirely characteristic of the local point of view:

Waitress: „Yet another beer?“

Citizen: „What a question!“

„The Bavarian can put up with anything,“ runs a well-known proverb, „even with the fires of purgatory, if only he can have his beer.“ It flows in his veins; and one is sometimes tempted to call what flows beneath the beautiful bridges „the Isarbrau.“

The saying goes that those landmarks, the twin towers of the Church of Our Lady, are capped by two great beer-mugs. And the city's symbol is the far-famed Miinchener Kindl — a boy in a monk's habit and often with a stein in his hand. Legend explains the figure by telling how our Saviour once came down, disguised as a little child, to bless the place and further the good works of the monks, who were the original local brewers. In this connection it is interesting to know that Cloister Schäftlarn, the germ of Munich, still turns out an excellent brew.

For many centuries the quality of Munich beer has been jealously guarded by law. There is an amusing rhymed legend about the methods of inspection. Three chosen councilors went to the brewery, but instead of pouring the beer down their throats, they poured it upon a bench, sat down together, then rose, said started for the door. If the bench accompanied them all the way, then the beer was strong and good. „But in these degenerate days,“ wails the chronicler, „far from having the bench stick to them, they stick, instead, to the bench!“

A marked trait of this hearty people is their devotion to the ancient line of Wittelsbach. In temperament many of the dukes and kings of Bavaria have shown themselves true Müncheners, specially in their love of beauty; and while, in many cases, their architectural taste has not fully expressed the character of the people, yet, from the first ducal castle down to the National Museum and the new bridges, the Wittelsbachs have filled the centuries with architecture which is, on the whole, racy of the soil, though many of the buildings are in the styles of distant ages and nations.

These Wittelsbachs have been closer to their people than most ruling houses, and some of them have been loved in return as kindred spirits. It is touching to remember how they would call out to Max Joseph as he rode past in troublous times: „Weil du nur da bist, Maxl, ist alles gut.“ („Seeing you 're here, Many, everything 's all right.“) On the abdication of their Maecenas, Ludwig I, they brought the old man to tears with their wild demonstrations of affection; and aged citizens have told me that heartbreaking scenes were witnessed when it became known that mad Ludwig II had taken his own life.

The earlier Wittelsbach architecture is more in harmony with Munich character than is the later. There is the romantic „Old Court,“ on the site of the first ducal castle, with its Gothic portals and façades, its picturesque, dunce-capped oriel window, and the quaint fountain murmuring in the center.

Near by, from a lane behind the post-office, one comes suddenly upon the old Tourney Court, now called the Court of the Mint. It is a typical work of the German Renaissance. The oblong space is surrounded by three tiers of colonnades, and the squat, dusky-red pillars and flattened arches breathe the ponderous Gemutlichheit of the days when Munich used to applaud the flower of Bavarian nobility breaking lances in the lists below, the pavement of which is now littered with the charcoal and the crucibles of the royal mint.

About the palace itself there hangs little of the atmosphere of olden days. For each ruler of the long line felt it his duty to add to, subtract from, multiply, and divide this huge complex, until the medieval was almost eliminated, and many of the later portions became unimpassioned echoes of French or Italian prototypes. For all this, there are a few parts of the palace that delightfully reflect the Miinchener. „Wherever the garment of foreign style did not quite come together,“ as Weese quaintly says, „the honest German skin peeped through.“

In the long, formal sweep of the western façade, for example, a bronze Madonna stands in a niche above an ever-glowing light, a tender German motif borrowed from the highland farmhouse, with its wooden patron saint.

In the Grotto Court one comes suddenly on a delightful instance of Bavarian charm — a vivid fleck of soft turf full of water-babies on ivied pedestals surrounding a fountain of Perseus worthy of the streets of old Augsburg. The plashing of the water, the cool greens and yellows of the palace walls, the perfect patina of the sculptures, the fantastic shell grotto at one end — all make a pleasant contrast to the monotonous splendors of the long festal suites within.

In the Fountain Court there is less of dreamy charm and more of the carnival spirit. On a jolly rococo pedestal of mossed stone poses Otto the Great, with his eye on the crowd of frivolous water deities below, among whom are the genii of the four rollicking rivers of Bavaria. They have that lovely iridescence which seems to thrive best on the bronzes of Munich, and which is specially brilliant on the Little Red Riding-Hood fountain in the Platzl.

The archway leading to the Chapel Court contains some reminders of the good old days. Chained to the earth is a black stone weighing about four hundred pounds. A rhymed inscription relates how, in the year 1490, Duke Christopher picked it up and „hurled it far without injuring himself.“ This is the same hero who, at the corner of the Marien-Platz called Wurmeck, killed a dragon that was terrorizing the town. It seems that the good duke was in love with a beautiful and popular daughter of the people, and that he agreed with his two rival suitors to hold a sort of field-day and let the best man win the maiden. The first event was putting the stone, and Christopher won. The second was hitch-kicking, and three nails in the wall immortalize the three astonishing records. The inscription proceeds:

Drey Nägel stecken hie vor Augen,

Die mag ein jeder Springer schaugen,

Der höchste zwölf Schuech vun der Erdt,

Den Herzog Christoph Ehrenwerth

Mit seinem Fuess herab that schlagen.

Kunrath luef bis zum ander' Nagel,

Wol vo' der Erdt zehnthalb Schuech,

Neunthalben Philipp Springer luef,

Zum dritten Nagel an der Wandt.

Wer höher springt, wird auch bekannt.

(Before your eyes protrude nails three

Which every jumper ought to see.

The highest, twelve shoes from the earth,

Duke Christopher, a man of worth,

Kicked from its proud position there.

Conrad leaped up into the air

Unto the second — ten shoes steep.

Unto the third — Phil Springer's leap —

Was nine and a half shoes from the ground.

Who higher leaps will be renowned. )

The poet Görres concludes a lyric on this event with the apposite wish:

Und möge unsern Fürsten all

Der liebe Gott verleihn

Aus jeder Noth den rechten Sprung

Und Kraft für jeden Stein.

(And may the dear Lord to each one

Of all our rulers loan

Skill to leap out of every ill

And strength for every stone.)

Where mthin palace gates is to be found a more striking memorial of good-fellowship between ruler and subject?

In its ground-plan, in its monumental façades and its long flights of festal cliambers, the palace shows a simple, reposeful breadth that is characteristic of the city and its people. It is the sort of breadth that one looks for in the work of great artists. And one imagines that there has entered into the Münchener something of the generous, free spirit of his marbles from Ægina, of his Titian canvases, and of the calm strength of his hills.

He is built on large, deliberate lines— a person not to be hurried or crowded. His speech is broad and slow, and even his graves are set unusually far from one another.

This large quality is specially marked in Munich's four monumental streets. The Brienner-Strasse takes its stately way from the portal of the Royal Gardens to the Königs-Platz, a square the simple majesty of which might suggest the Athenian Acropolis. In front is the Doric dignity of the Propylæa, erected to celebrate in advance Bavaria's ill-fated attempt to shake Greece free of Turkey. On each hand are Ionic and Corinthian temples, devoted respectively to sculpture and the Secessionist school of painting. Between these serene, broadly modeled buildings lie only stretches of turf and roadway.

The great simplicity of such a scene is exaggerated in the Ludwig-Strasse into monotonous austerity, especially where the hard Roman Arch of Triumph, the cloister-like university, the Ludwig Church, and the public buildings line up their dreary façades. But, in spite of these, it is an imposing street. It shows at its best when the sun of early afternoon slants down to correct its horizontal lines, or when, at sunset, every homely westward road becomes a flaming way to some enchanted castle, and, behind the Hall of Generals, the tower of the New Rathaus changes in the glow to a tower of quicksilver. The southern end of the Ludwig-Strasse is most delightful at noon, when the military band plays and the gay crowd comes to promenade and see the Royal Guard relieved.

These newer parts of Munich have been called the Wittelsbachs' note-book of travel, where they have recorded in stone and bronze their deepest impressions of other lands. In the Königs-Platz they wrote down their love of Greece, and their love of Italy in the Odeons-Platz.

The Hall of Generals is a copy of the Florentine Loggia dei Lanzi; the church of the Theatines on the right was modeled after the Church of S. Andrea della Valle in Rome; on the left, the western f a9ade of the palace is typically Italian, while the southern was actually copied from the Pitti Palace. The very pigeons graciously peck corn from the palms of American tourists in the accepted Venetian manner. One sees over the foliage of the Royal Garden the iridescence of the Army Museum's dome and the lordly tower of St. Anna's, and involuntarily glances about, wondering why there are no dark-skinned folk sipping their wine on the sidewalk; why no forms in roseate rags lie asleep on the steps of the loggia, and why no melting voice and prehensile fingers are touching one's heart and sleeve for ”un soldo!“

Though the Maximihans-Strasse is unfortunate architecturally, yet there is the same grand manner in its round-arched buildings, and something nobly commanding in the way the Maximilianeum dominates the city from among the gardens across the Isar.

With its splendid new home for Wagnerian musicdrama and its National Museum, the modern Prinzregenten-Strasse, laid out by some inspiration in a gentle, medieval curve, shows that the city is not lagging behind her traditions.

The best exemplar of this quality of reposeful breadth, the Church of Our Lady, is exemplar also of another leading trait of Munich — her deep relig- ious spirit. In fact, these simple, massive walls, adorned outside and in with quaint and beautiful carvings and paintings, seem to epitomize the whole Miinchener. Some of the tombstones, like that of the blind musician, are even suffused with a kindly humor; and around the mausoleum of Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian, a worthy companion piece to Maximilian's tomb at Innsbruck, one may see the love these warm-hearted people still bear to one who made Munich's fortunes his own. Among the many legends that cluster here is one of this emperor, who was found, centuries after his death, in the crypt under the mausoleum, sitting upright on his throne, as Charlemagne is said to have been found at Aix-la- Chapelle.

There is a black footprint on the pavement under the organ-loft at a place where a curious architectural trick has made all the windows invisible. There one is told how the builder of the church made a compact with the devil, who agreed to help him on condition that God's sunlight should be kept out of the building. The devil saw the windows growing, and was glad. „Come along with me,“ said he to the builder. „Come along yourself,“ cried the builder, and led him under the choir-loft. The devil looked in vain for a window, stamped his foot in impotent rage, and vanished. But his footprint has remained to this day.

The builder of St. Michael's was less fortunate, for when he had completed the bold barrel-vaulting that spans the most noteworthy of German Renaissance halls, it is said that he cast himself from the roof in despair, fearing that his work would not stand. This majestic church was built by the Jesuits to celebrate the coming triumph of the Counter-Reformation. It was an eloquent prophecy of Munich's present Roman Catholic solidarity.

St. Peter's is the oldest local church, and contains the choicest tombstones; but the interior has suffered shockingly from the vandals of baroque times.

These older examples of the Munich churches well represent the broad, simple, reposeful characteristics of the place. Certain younger ones, however, like All Saints', Trinity, St. John's, and the Church of the Jesuits, fairly sparkle, in their baroque and rococo finery, with the carnival spirit.

The most noteworthy modern churches are the Court Church, a little Byzantine pearl of a place that transports one in a breath to the atmosphere of the Cappella Palatina at Palermo; and the Basilica of St. Boniface, Ludwig's record of his most precious hours in Ravenna and Rome. But, of all the later churches, St. Anna's is my favorite. Built of rough coquina, its picturesque complex of gables, turrets, and spires grouped about the central tower is already finely weathered. The broad, walled terrace, the moated fountain borne on pillars, the deeply felt modeling of the façade, the portal worthy of some great medieval builder — all these blend in an ensemble the equal of which I have not seen elsewhere in modern Romanesque architecture.

All these churches are real places of worship. One finds there the same spirit of fervor that one expects to find in Tyrol or Italy. And this is natural, for the city grew out of a religious institution near by, and its very name — Ad Monachos, or „At the Monks“ — stamps it as the child of Cloister Schäftlarn. The whole daily walk and conversation of the people is connected in some way with ecclesiasticism. They say of anything that moves rapidly: „It runs like a paternoster“; of a heavy drinker, „He guzzles like a Knight Templar.“ A mild state of intoxication is called a Jesuitenräuschlein; while an unfortunate in the advanced stages is „as drunk as a Capuchin father.“

In Catholic communities farther north there is a strain of cooler intellectuality in the devotions of the people. Here all is emotion. In fact, until recently this lack of balance has had a grievous effect on Munich's intellectual life, which can boast few writers of note. But it has, on the other hand, kept a warm place in the hearts of the people for romantic legends and superstitions. The Münchener has clung so much more successfully to these beliefs than to his medieval buildings that the place gives the illusion of having more atmosphere than its architecture would warrant.

The folk still call Tuesday and Thursday by the ancient names, Irtag ( day of the war-god Ares ) and Pfinztag, from the Greek for Fifth Day.

On Twelfth Night they cast evil spirits out of their homes with a ceremony descended in substance directly from the heathen rites of Odin. They move from room to room, sprinkling the powder of sacred herbs on a shovelful of live coals, and write up over every door with consecrated chalk the mystic initials †C †M †B. These letters stand for the three Wise Men of the East, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar.

This is of a piece with the conservative instinct that still continues the Passion Play in the neighboring village of Oberammergau.

With their Bavarian zest m anecdote, the people love to tell of a basilisk which lived in a well on the Schrammer-Gasse opposite the present bureau of police. The glance of this medieval Medusa killed all who looked at it, until some German Perseus held a mirror over the well and let the creature slay itself.

The local belief in witches and black art is wonder- fully persistent. Tales are still current of spirits who took the form of black calves and could be out- witted only by being banned into a tin bottle with a screw-top. There is the legend of an unprincipled lawyer who died and was laid out in the usual way with crucifix and candles. All at once two black ravens appeared at the window, broke the pane with their beaks, and flew away again with a third raven which suddenly appeared from within the chamber of death. The candles were quenched in a trice, the crucifix overturned, and the lawyer's corpse turned as black as night.

Then there is the favorite story of Diez von Swinburg, a robber knight who, with four of his men, was caught and condemned to death. Diez begged in vain for the lives of his comrades. Finally he cried: „Will you, then, spare as many as I run past after I have been beheaded?“ With contemptuous laughter the request was granted.

Diez placed his men in a line, eight feet apart, with those he loved best nearest him. Well pleased, he knelt down. His head fell. Then he rose, turned, ran stumbling past all of his followers, and collapsed in a heap.

People who cherish such beliefs do not easily give up time-honored customs, and Munich is still rich in romantic rites. During the plague of 1517, when half the city lay dead and the other half was stricken with despair, the Gild of Coopers gave every one fresh heart by organizing an impromptu carnival of dance and song in those terrible streets. Once every seven years, in honor of this act, the Schäffler Tanz, or Coopers' Dance, still takes place, the coopers dancing in their ancient garb — green caps, red satin doublets, long white hose — and carrying half-hoops bound with evergreen.

Sad to say, the picturesque Metzgersprung, or Butchers' Leap, has been recently done away. After a jolly round of dancing and parades and a service in „The Old Peter,“ the Butchers' Gild would meet around the Fish Fountain in the Marien-Platz and, after elaborate ceremonies, the graduating apprentices, dressed in calfskins, would leap into the basin and thus be baptized as full-fledged butchers.

In this same beloved square the pick of all Munich, old and young, joins in the Corpus Christi procession, which, gay with students' caps and banners and guild-insignia, winds from the Church of Our Lady and groups its rainbow colors around the old Pillar of Mary, where the archbishop, who has been preceded by white-robed maidens with flowers and candles, reads the Scriptures.

Despite its worship of the past, however, Munich is, on the whole, a progressive city. Its recent commercial strides have been astonishing. For a century it has led Germany in artistic matters. And that it still leads, is shown by its annual exhibitions of painting and sculpture, of arts and crafts, and by such architecture as the National Museum, St. Anna's, the building of the „Allgemeine Zeitung,“ and some of the new school-houses.

The Isar Valley, Schleissheim, and Nymphenburg belong even more intimately to Munich than the Havel and Potsdam belong to Berlin. To wander through the fragrant woods and by the castles and quaint villages of the Isar gorge is to hear and see the Münchener at his best. For he is always taking a few hours off there, and is always laughing and singing and yodeling. It seems as though the happy creature cannot turn his face away from town and swing into stride without breaking into one of his hearty songs.

The castle of Schleissheim was built, like St. Michael's and the Propylsea, to celebrate a future triumph. For Max Emanuel imagined that he was going to be elected emperor, and could not restrain his exuberance at the thought. Those splendid baroque halls never held his imperial court, for he was driven into exile before they were finished; but they hold to-day one of the foremost Bavarian collections of paintings, especially rich in the old German school. The formal gardens, with their statues, vases, and tree-fringed waters, contrast pleasantly with the severe facades of the castle, and form a sort of prelude to the more generous scale of Nymphenburg, the most lovable of all the many German paraphrases of Versailles.

My first visit to Nymphenburg was on a perfect afternoon in late summer. I came into a circle of buildings almost a mile in circumference, a barren, baroque circle inclosing a cheerless waste full of ugly canals and ponds, where the lords and ladies of the eighteenth century, in their gondolas, used to ape the water fetes of France and Italy. There is all too little of the festal spirit left there now.

But on the other side of the castle the atmosphere changed like magic. I plunged into a brilliant Versailles, but a sweeter, more gemütlich one than any of my acquaintance— a vast garden that knew how to be at once formal and natural. There was a wide sweep of lawn where old women and bullocks and rustic wains were busied with haycocks among long rows of marble deities and urns. In the middle of the scene a fountain flashed high in the sunlight, falling among rough rocks. Humorous lines of Noah's Ark evergreens stood attention. In the distance, beyond a linden-flanked canal, were waterfalls; and one caught a glimpse of the misty horizon. Right and left, narrower lanes of foliage opened vistas of water-flecked lawns checkered with patches of sunlight. Far away gleamed little pools, as bright as pools of molten steel, and near one of them I came upon a dream of a summer-house called the Amalienburg, one of the most delicate and radiant bits of rococo fantasy in the German land.

Munich is so diffuse a city that it is hard to think of it as a unit until one has seen it from some high place. It was a revelation to me when I climbed past the chimes of „The Old Peter“ to the town-pipers' balcony. There lay the city as flat as a lake. To the westward was a jumble of sharp, tiled roofs, turning the skylights of myriad studios searchingly toward heaven, as though the houses were all bespectacled professors. Beyond the eloquent front of St. Michael's rose the court of justice in all its dignity, with the humorous annex which the murderer begged to see. The Church of Our Lady towered over old Munich, symbol of the warm South-German heart. Immediately to the north rose that „mount of marble“ the New Rathaus, a, reminder of Milan cathedral, in its dazzling, restless opulence, and with a touch of the theatrical manner seen beside the quiet comeliness and reserve of the Old Rathaus. Beyond, the Pitti-like façade of the palace stood out against the soft leagues of the English Garden. Eastward the Maximilianeum's perforated front reposed like a well-kept ruin amid the luxuriance of its waterside park. The Isar, itself invisible, made a bright zone of green through the city; and in the south, crowning and glorifying the whole scene, the snow glistened on the far peaks of the Bavarian Highlands.

A party of students had come up, and were gazing with affectionate eyes on their city. Quite without warning they burst into a song which I shall always associate with that tower and its glorious panorama:

So lang die grüne Isar durch d' Münchnerstadt noch geht

So lang der alte Peter auf 'm Peter's-Platz noch steht,

So lang dort unt' am Platzl noch steht das Hofbräuhaus,

So lang stirbt die Gemütlichkeit in München gar net aus.

Freely rendered:

So long as through our Munich the Isar rushes green,

So long as on St. Peter's Place Old Peter still is seen,

So long as in the Platzl the Court-brew shall men nourish.

So long the glowing, kindly heart of Munich-town shall flourish.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

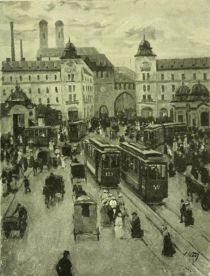

Munich — Karls Place,looking toward Karls Gate, and the Church of Our Lady. Painted by Charles Vetter.

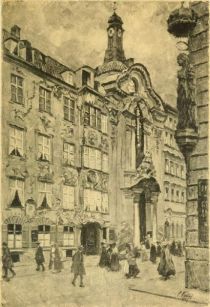

Munich — Church of St. John. Drawn by Charles Vetter.

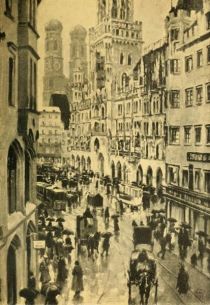

Munich — Court of the Hofbräuhaus (Royal Brewery). Painted by Charles Vetter.

Munich — The Maximilianeum and the Isar. Painted by Charles Vetter.

Munich — The Church of St. Anna. Painted by Charles Vetter.

Munich — The Gardens of Nymphenburg. Painted by Charles Vetter.

Munich — The New Rathaus in the middle ground, and the Towers of the Church of Our Lady, in the distance. Painted by Charles Vetter.

alle Kapitel sehen