VIII. Meissen.

Therer were roses as large as hollyhocks in the station garden at Meissen, and the fragrance of new-mown hay filled the air. We were warmly greeted by the ticket-taker, a gentle spirit with beautiful eyes, who kindly carried our bags to the hotel above the Elbe.

We strolled down to a shore vaguely littered with boats, fishing-nets, and rude carts — a strange shore lying pallid in the last light of day. High on the opposite ridge a spirelet, like a wren's upturned beak, was silhouetted against the south. Colin rose sheer and mysterious above the backward crags, falling away with a quaint effect toward where, far distant, a windmill on the sky-line beckoned Dresden with fantastic fingers, while the crimson lights of the Old Bridge swam in a shimmer of water that Thaulow might have painted.

On the opposite side of the river the town reached up in a lovely line to the pile of the Albrechtsburg, looming gigantic in the dusk, its cathedral towers swathed in a scaffolding exquisitely etched against the faint robin's-egg blue of the sky.

As I gazed, uncouth figures slouched past; and by the glow of a pijje I recognized on the Old Bridge one of those mysterious Low-Country faces which Rembrandt loved. Boats with red and golden eyes slipped beneath us, towing strings of serpentlike barges; and down the black lane at the bridgeend a light flickered in a noble tower, rounding a vision that belonged less to Germany than to such lands of delight as children explore on the hearth-rug before falling embers.

As the west blackened and lights spread through the town, my friend the artist came slowly out of his trance. „When I first caught sight of this,“ he murmured in his rich Austrian dialect, „it was as though a great painter had spread before me a masterpiece, saying, 'Na, bist zufrieden?' ['Well, art content?'] I shall no more forget it than the moment when I first saw the sea, and would have leaped to it through my window!“

Under the sky of early morning, dainty with small, tenderly tinted clouds, Meissen became really German. Below the Burg the tiles came out in a glow of rare mellowness. Though the atmosphere was as soft as that of rural England, the Elbe disengaged the ozone, the bracing salt smell of the sea down beyond Hamburg. Behind the carts, the junk, the weedy, net-littered stones of the opposite quay, squatted buildings that bore in their foreheads windows like great eyes peeping through the tiles under an arch of frowning brow. „Ox-eyes“ the people call them.

Every house was bright with flowers, and every woman carried at least one blossom in her market-basket. A maid in a short, gay petticoat was singing a folk-song as she brushed her dooryard with a bundle of twigs. A genial crone went by bare- legged, harnessed with a dog to a cart full of fascinating earthenware, her silvery head-dress drawn tight over her silvery head — a sight to move a very sign-painter. In a stable door by the waterside sat a tiny maid, with flying curls, crooning a song to two baby goats in white and brown that were enthusias- tically eating oats out of her lap. „I am 'Lisbeth,“ she answered me, „and these“ — patting her bearded friends— „are Fritz and Hans.“

With a sudden expansion of the heart I realized that I had entered the brighter atmosphere of a wine country, and that this was a foretaste of the dear, kindly South-German land.

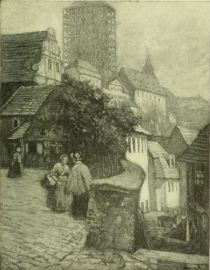

Meissen is a town of crooked streets that wind about delightfully in its depths, and suddenly climb the heights on each hand — a town with a fresh surprise of architecture, of costume, or of landscape at every turn. One is constantly finding some landing whence ancient walled steps shoot up on the one hand to the Burg, and down on the other hand to the river.

I climbed the ”Ascent of Souls“ beside an ivied wall weathered all colors. Where the corner of a house jutted out informally above the passers-by was an intimate view of the Town Church belfry, which had crowned the previous evening's pleasure. Past the Princes' School, where Gellert and Lessing once studied, the way led to the fourteenth-century Church of St. Afra, the Cyprian princess martyred at Augsburg by Diocletian in the year 303, whose soul flew to heaven a white dove, leaving her body unharmed by the flames. The chroniclers say that Dante taught in the cloister-school in 1307.

Through a tower-gate and by the fine, Romanesque portal of the Waschhof, I passed from the Afra Mountain over a medieval viaduct to the Castle Mountain, regions both formerly independent of Meissen law, and called „Freedom“ to this day.

Massive, august, the Albrechtsburg, with its outbuildings, spreads protecting arms about the thirteenth-century cathedral, the richest and most beautiful of the churches of Saxony. There, in the Princes' Chapel, before the western facade, beneath the bronzes of Peter Vischer, lie the Saxon rulers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, on whom look down primitive statues of the Magi and the crowd of Gothic saints and angels on the main portal.

The church windows are of Putzenscheiben, the same small, round panes with a bubble of glass in the center which gave Rembrandt his iridescent gloom; but in the choir still glows stained glass of the fourteenth century.

The pavement is covered with gravestones and brazen slabs. Here is the resting-place of Dr. Johann Hofmann, who, after quarreling with John Huss, seceded from Prague with a throng of German professors and students to found Leipsic University. Here is the grave of Dr. Günther, who was killed by the same bolt that shattered the steeples in April, 1547; and here, until the Reformation, was the tomb of Benno, the saint who, according to report, worked miracles while alive, and whose bones healed the sick more than four hundred years after his death.

Before the high altar lies Margrave William the One-eyed under a slab showing where the bronze plate was torn away by the Swedes of Gustavus Adolphus. Legend says that this William oppressed the clergy who prayed to the holy Benno. Benno warned William in a vision, much to the Margrave's amusement; but at his second appearance the saint burned out one of William's eyes with a torch. Whereupon the Margrave saw that it had been no dream, and made fourfold restitution.

The cathedral is famous for the variety of its ornamentation, and no two of its five hundred capitals bear the same foliage. Near the high altar is an exquisite Gothic tabernacle, and near by, over the sacristy door, are statues of Emperor Otto I, who built the original cathedral in 965, and of his smiling wife Adelheid, both masterpieces of thirteenth-century sculpture.

The vaulting of the sacristy is carried, as in Auerbach's Keller, by a single pillar. And there, through the small, rusty-barred, ivy-smothered windows of Putzenscheiben, I caught a glimpse, across the Elbe, of red crags and green meadows, and my friend the windmill still spinning eagerly on the sky-line. With a right good will my pfennigs dropped into a box marked „For the Heathen,“ poor people who could not see such things.

A trap-door uncovered steps leading to a similar room underneath, from which more steps plunged to a still gloomier chamber in the bowels of the hill, both dating from Otto's tenth-century church.

I was glad to come out again into the nave, where a young bird was flying about contentedly between the slender piers under the groined branches of the vaulting. It disappeared through a transept. I followed, and came out into a little cloister, the key-note of the whole cathedral concord. Massive, uncloister-like, ivy-draped piers inclosed with lovely pointed arches a square full of ferns and foliage, a fitting place to ruminate the day's experience and to enjoy the steeple above the choir.

The Albrechtsburg, one of the finest of fifteenth-century castles, is the successor of a stronghold built in 928 by Henry I in the long German struggle against the Slavic inhabitants of the mark of Meissen. It was begun in 1471 by the noted architect Arnold of Westphalia, and until the court was transferred to Dresden was the residence of the Saxon princes. After that it long lay neglected; then for a century and a half it suffered the indignity of serving as the royal porcelain factory. In 1881 it was restored and over-decorated, so that the exterior is more noteworthy than the long line of nobly vaulted and gaily frescoed halls which strangers visit. The glory of the Burg is its stair-tower, with wide Gothic arches framing the spiral stair inside. It is covered with convivial reliefs, taken, according to the guide, „from the profane life.“ They are of the same period as those on the famous Rathaus in Breslau, and aknost as grossly humorous.

I like to think that from this fair Castle Mountain Christianity and culture spread in waves through central Germany, and that it was the base for the great military expeditions by which the hero Albrecht helped to lay for Saxony the foundations of national unity.

The porcelain factory in the Triebisch-Thal, interesting as it is, has quite unjustly monopolized the fame of Meissen. And a glimpse of the Burg from the riverside, a ramble up the Ascent of Souls, or a moment in the cloister of the cathedral, is far to be preferred to a whole Triebisch-Thal full of Meissen services and rococo figurines.

We strolled down to a shore vaguely littered with boats, fishing-nets, and rude carts — a strange shore lying pallid in the last light of day. High on the opposite ridge a spirelet, like a wren's upturned beak, was silhouetted against the south. Colin rose sheer and mysterious above the backward crags, falling away with a quaint effect toward where, far distant, a windmill on the sky-line beckoned Dresden with fantastic fingers, while the crimson lights of the Old Bridge swam in a shimmer of water that Thaulow might have painted.

On the opposite side of the river the town reached up in a lovely line to the pile of the Albrechtsburg, looming gigantic in the dusk, its cathedral towers swathed in a scaffolding exquisitely etched against the faint robin's-egg blue of the sky.

As I gazed, uncouth figures slouched past; and by the glow of a pijje I recognized on the Old Bridge one of those mysterious Low-Country faces which Rembrandt loved. Boats with red and golden eyes slipped beneath us, towing strings of serpentlike barges; and down the black lane at the bridgeend a light flickered in a noble tower, rounding a vision that belonged less to Germany than to such lands of delight as children explore on the hearth-rug before falling embers.

As the west blackened and lights spread through the town, my friend the artist came slowly out of his trance. „When I first caught sight of this,“ he murmured in his rich Austrian dialect, „it was as though a great painter had spread before me a masterpiece, saying, 'Na, bist zufrieden?' ['Well, art content?'] I shall no more forget it than the moment when I first saw the sea, and would have leaped to it through my window!“

Under the sky of early morning, dainty with small, tenderly tinted clouds, Meissen became really German. Below the Burg the tiles came out in a glow of rare mellowness. Though the atmosphere was as soft as that of rural England, the Elbe disengaged the ozone, the bracing salt smell of the sea down beyond Hamburg. Behind the carts, the junk, the weedy, net-littered stones of the opposite quay, squatted buildings that bore in their foreheads windows like great eyes peeping through the tiles under an arch of frowning brow. „Ox-eyes“ the people call them.

Every house was bright with flowers, and every woman carried at least one blossom in her market-basket. A maid in a short, gay petticoat was singing a folk-song as she brushed her dooryard with a bundle of twigs. A genial crone went by bare- legged, harnessed with a dog to a cart full of fascinating earthenware, her silvery head-dress drawn tight over her silvery head — a sight to move a very sign-painter. In a stable door by the waterside sat a tiny maid, with flying curls, crooning a song to two baby goats in white and brown that were enthusias- tically eating oats out of her lap. „I am 'Lisbeth,“ she answered me, „and these“ — patting her bearded friends— „are Fritz and Hans.“

With a sudden expansion of the heart I realized that I had entered the brighter atmosphere of a wine country, and that this was a foretaste of the dear, kindly South-German land.

Meissen is a town of crooked streets that wind about delightfully in its depths, and suddenly climb the heights on each hand — a town with a fresh surprise of architecture, of costume, or of landscape at every turn. One is constantly finding some landing whence ancient walled steps shoot up on the one hand to the Burg, and down on the other hand to the river.

I climbed the ”Ascent of Souls“ beside an ivied wall weathered all colors. Where the corner of a house jutted out informally above the passers-by was an intimate view of the Town Church belfry, which had crowned the previous evening's pleasure. Past the Princes' School, where Gellert and Lessing once studied, the way led to the fourteenth-century Church of St. Afra, the Cyprian princess martyred at Augsburg by Diocletian in the year 303, whose soul flew to heaven a white dove, leaving her body unharmed by the flames. The chroniclers say that Dante taught in the cloister-school in 1307.

Through a tower-gate and by the fine, Romanesque portal of the Waschhof, I passed from the Afra Mountain over a medieval viaduct to the Castle Mountain, regions both formerly independent of Meissen law, and called „Freedom“ to this day.

Massive, august, the Albrechtsburg, with its outbuildings, spreads protecting arms about the thirteenth-century cathedral, the richest and most beautiful of the churches of Saxony. There, in the Princes' Chapel, before the western facade, beneath the bronzes of Peter Vischer, lie the Saxon rulers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, on whom look down primitive statues of the Magi and the crowd of Gothic saints and angels on the main portal.

The church windows are of Putzenscheiben, the same small, round panes with a bubble of glass in the center which gave Rembrandt his iridescent gloom; but in the choir still glows stained glass of the fourteenth century.

The pavement is covered with gravestones and brazen slabs. Here is the resting-place of Dr. Johann Hofmann, who, after quarreling with John Huss, seceded from Prague with a throng of German professors and students to found Leipsic University. Here is the grave of Dr. Günther, who was killed by the same bolt that shattered the steeples in April, 1547; and here, until the Reformation, was the tomb of Benno, the saint who, according to report, worked miracles while alive, and whose bones healed the sick more than four hundred years after his death.

Before the high altar lies Margrave William the One-eyed under a slab showing where the bronze plate was torn away by the Swedes of Gustavus Adolphus. Legend says that this William oppressed the clergy who prayed to the holy Benno. Benno warned William in a vision, much to the Margrave's amusement; but at his second appearance the saint burned out one of William's eyes with a torch. Whereupon the Margrave saw that it had been no dream, and made fourfold restitution.

The cathedral is famous for the variety of its ornamentation, and no two of its five hundred capitals bear the same foliage. Near the high altar is an exquisite Gothic tabernacle, and near by, over the sacristy door, are statues of Emperor Otto I, who built the original cathedral in 965, and of his smiling wife Adelheid, both masterpieces of thirteenth-century sculpture.

The vaulting of the sacristy is carried, as in Auerbach's Keller, by a single pillar. And there, through the small, rusty-barred, ivy-smothered windows of Putzenscheiben, I caught a glimpse, across the Elbe, of red crags and green meadows, and my friend the windmill still spinning eagerly on the sky-line. With a right good will my pfennigs dropped into a box marked „For the Heathen,“ poor people who could not see such things.

A trap-door uncovered steps leading to a similar room underneath, from which more steps plunged to a still gloomier chamber in the bowels of the hill, both dating from Otto's tenth-century church.

I was glad to come out again into the nave, where a young bird was flying about contentedly between the slender piers under the groined branches of the vaulting. It disappeared through a transept. I followed, and came out into a little cloister, the key-note of the whole cathedral concord. Massive, uncloister-like, ivy-draped piers inclosed with lovely pointed arches a square full of ferns and foliage, a fitting place to ruminate the day's experience and to enjoy the steeple above the choir.

The Albrechtsburg, one of the finest of fifteenth-century castles, is the successor of a stronghold built in 928 by Henry I in the long German struggle against the Slavic inhabitants of the mark of Meissen. It was begun in 1471 by the noted architect Arnold of Westphalia, and until the court was transferred to Dresden was the residence of the Saxon princes. After that it long lay neglected; then for a century and a half it suffered the indignity of serving as the royal porcelain factory. In 1881 it was restored and over-decorated, so that the exterior is more noteworthy than the long line of nobly vaulted and gaily frescoed halls which strangers visit. The glory of the Burg is its stair-tower, with wide Gothic arches framing the spiral stair inside. It is covered with convivial reliefs, taken, according to the guide, „from the profane life.“ They are of the same period as those on the famous Rathaus in Breslau, and aknost as grossly humorous.

I like to think that from this fair Castle Mountain Christianity and culture spread in waves through central Germany, and that it was the base for the great military expeditions by which the hero Albrecht helped to lay for Saxony the foundations of national unity.

The porcelain factory in the Triebisch-Thal, interesting as it is, has quite unjustly monopolized the fame of Meissen. And a glimpse of the Burg from the riverside, a ramble up the Ascent of Souls, or a moment in the cloister of the cathedral, is far to be preferred to a whole Triebisch-Thal full of Meissen services and rococo figurines.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

Meissen — from the right bank of the Elbe. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Meissen — Ascent to the Albrechtsburg. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

alle Kapitel sehen