VII. Leipsic.

In visiting northern Germany the traveler usually keeps the Prussian capital as his base of operations until he seeks the South by way of Saxony.

After the aggressiveness and modernity of Berlin, it is a relief to mingle with the quiet, matter-of-fact people of Leipsic, to rest one's eyes again on a Renaissance gable, again to loiter in streets with quaint and homely names. In many of these old names there is a flavor of poetry that brings the stranger at once into terms of intimacy with the town. They touch the imagination because they were christened naturally by the wit of the people, and always christened for their most salient feature.

Windmill Alley led in bygone days to a mill beyond the wall and ditch; along Sparrow Mountain, a thoroughfare almost as flat as Sahara, ran a prison wall, crowded winter and summer with sparrows. Begging Street pierced the slums. In Barefoot Alley was a cloister of ascetic monks, and the chivalry of the Middle Ages lived in Knight Street. „Along Milk Island“ was over against a dairy, while from Pearl-stringer Alley, Tub-maker Street, Bell- caster Street, Night-watchman Street, and Rubber Alley the corresponding occupations have not yet wholly passed away. In olden times one small lane actually bore three names simultaneously: Town Piper Alley, Constable Alley, and Midwife Alley; for these personages all dwelt there. The Brühl, called after a Slavic word for swamp, is the only street to commemorate the Wendish origin of the city and the patience of its builders; but though a few of these delightful names have passed away through sheer anachronism, enough are left to give the place an intimate, Old-World, human flavor. A city that preserves a Barefoot Alley deserves well of mankind, and I prefer small beer within its shadows to the bright new champagne of North Street.

To one who for a time had half forgotten that the larger German cities still held anything old, the Princes' House in the Grimmaische-Strasse brought a delightful shock of recognition. From those round red oriel windows flanking the gable, sixteenth-century princes used to display their finery to the folk below — student princes who came to study in the university round the corner and left their coats of arms among the carvings on the window- sills. The house is Leipsic's best example of the German Renaissance.

Through a narrow gulf of street the oldest church looks down upon this corner. The Church of St. Nicholas was built in 1017, two years after the city was first mentioned in history as Urbs Libzi. Like the later churches, it suffered many things during the sieges of the Thirty Years' War, but not so sadly as from its „restoration“ in the „Wig Time.” Then the jealous vandals of classicism, with a naivete pathetic to recall, destroyed what beauty the baroque time had spared and threw the beautiful altarpieces of Cranach into the loft where Goethe discovered them in 1815, publishing the matter with righteous wrath. They are now in the museum.

Oppo'site the gracious green of St. Nicholas's tower is a hearty, rustic kind of architecture too seldom seen in cities, a red-timbered house with piquant gables, and a carved bay-window in rococo crowned by the motto,

Ohn' Gottes Gunst all Bau'n umsunst.

(By God ungraced, all building 's waste.)

The roof, broken by little gable-windows, leads the eye onward to the vivacity of old Leipsic's sky-line —red tiles tossed into heaps and flowing together as in a choppy sea, yet with a large unity, as if composed by a modern French sculptor of the rugged school.

Next door is the gaily frescoed facade of a peasants' inn, „The Village Jug,“ with uncouth windows of glass stained in every sense, the head of a red ox serving for signboard; while over beyond the church is a Renaissance gable with three superimposed orders of classical columns, its ancient colors quite worn away. For in the sixteenth century these stone fa9ades were all painted, „mit gar kunstreichen und lustigen Gemalde gebauet und ausgeputzet,“ writes an old chronicler. (Builded and. furbished with paintings „real art-rich“ and jolly.)

Passages as narrow as those of Hamburg run through baroque courtyards to the Reichs-Strasse — the Via Imperii of the Middle Ages— one of the two principal merchant highways through the Holy Roman Empire. This is richer than the Nikolai- Strasse in such façades as the „Castle Cellar,“ with its massive, undulating gable, its flat-arched doors of worm-eaten, iron-bound wood, and its barred, diag- onal window.

From the Grimmaische-Strasse close at hand I entered a large court and warmed one of Leipsic's reticent sons gradually into garrulity.

„Look about you,“ he said. „In olden times this Hof was called 'Little Leipsic,' just as Leipsic was then called 'Little Paris.' During the fairs the costliest articles of luxury were sold here, and it was the resort of fashion. Behold!“ He pointed out a half-hidden door. „I advise you to enter. You will see the most interesting nook in town.“

I groped my way down a crooked passage into a wine-cellar the Romanesque vaulting of which, mellow with old colors, was upheld by a single pillar covered with manuscripts. I spelled out a signature. It read „J. W. von Goethe.“ On the walls were pictures of the poet, a black silhouette of his student days, a musty print of Doctor Faustus. Bewildered, I sat down and strove to conjure up a sophomoric acquaintance with „Wahrheit und Dichtung.“ Then the waiter brought a bottle labeled „Auerbach's Keller,“ and with a gasp of joy I realized that this was the immortal den where Mephistopheles once bored holes in the table and made red and white wine spurt in fountains over the good burghers. Down in an ancient sub-cellar was a fresco from the time of the Thirty Years' War. Doctor Faustus was seated, with a convivial company and quaint musical instruments, above the following inscription:

Vive, bibe, obgraecare, memor Fausti hujus et hujus

Poenae. Aderat claudo haec — ast erat ampla — gradu.

Freely rendered;

Live, drink, go to the devil; mindful of Faustus' damnation.

It had a step that was halting, but it came swiftly enough.

Another scene showed the doctor galloping out of the arched entrance on a cask accompanied by this doggerel:

Doktor Faust zu dieser Frist

aus Auerbachs Keller geritten ist

auf einem Fass mit Wein geschwind

welches gesehn viel Menschenkind

solches durch subtile Kraft gethan

und des Teufels Lohn empfing daran.

These lines might be paraphrased:

At this season Dr. Faust

Out of Auerbach's Cellar coursed

On a wine-cask running wild,

Seen by many a mother's child —

Subtle artist at his play —

And the devil was to pay.

It appears that tradition actually connected some old master of Black Art with Auerbach's Cellar, which he used as a stable, to the confusion of all honest citizens. Toward the end of the sixteenth century the tradition was transferred to the still more legendary Faustus, and in this romantic setting, more than two centuries later, the student Goethe met with the shade of his greatest hero. There is a long subterranean passage still leading from the sub-cellar to the university; and, what is even more shocking, another runs to the site of a former convent in the neighborhood.

Behind the Old Rathaus opposite is the Nasch-Markt, or Candy Market. Near a statue of Goethe stands the old exchange, an early example of the sandstone baroque that was imported from Dresden and began to flourish after the barren times of the Thirty Years' War. Much of this architecture is yet visible in the northeast corner of the Old Market and in the patrician houses of Katharinen-Strasse, the Fifth Avenue of the eighteenth century. Strangely enough, the style has almost disappeared from among the dwellings of Dresden, and now Leipsic is richer than any other large German city in private baroque architecture. Even two hundred years ago the French and Italian student journeyed hither to study this gay, new art that was transforming low, dingy rooms into spacious, brilliant halls and chambers with great windows flamboyant in fruit, flowers, leaves, and shells, and tasseled lambrequins; with portals topped by urns of plenty bulging in significant relation to the well-fed pillars below — an art evolved directly from the interior decoration of the period.

The Old Market is dominated by the Old Rathaus, a Renaissance building with many brick gables, dusky tiles, and a duskier green tower which are devoutly worshiped by every true Leipsicker. Yet somehow it lacks the atmosphere of poetry which one expects in a Rathaus of its age and traditions. It is solid, matter-of-fact, mildly pleasing, like the average citizen, and appeals little more than he to the imagination until, inside, one sees the small pillared balcony, „the pipers' chair,“ where the town pipers used to play at patrician and plebeian festivities in the days when Leipsickers loved to dance in the great hall (“ufs Rathaus tanzen“).

There is more atmosphere about the house on the Brühl where young Goethe used to court his Gretchen, the awakener of his genius; and, significantly enough, on Kätchen Schönkopf's roof a well-weathered Apollo stands above Romanesque gateways and gratings, pointing toward heaven. The Brühl is a distinguished street. At Number 3 I entered, walking between rails into a Hof full of trucks and meal. And, set in a wall of brick and cement, was a simple tablet with the inscription:

In this house was born

Richard Wagner

May 22, 1813

On a hillock, perched above a picturesque line of roofs, the Church of St. Matthew is grateful to eyes wearied with the levelness of Leipsic. Here as in all flat lands every elevation is cherished, and an almost imperceptible rise in the Promenade-Ring, famous for its view of the New Rathaus, has been popularly christened the Promenade Wart. Indeed, in seeking the Schiller House in Gohlis, I was directed “bergauf” (literally, „up the mountain“) along a road where the rain-water was standing in pools. The site of St. Matthew's is more remarkable than its architecture, for the church is based on the ruins of Leipsic's first citadel, and looks over across the Pleisse to little Naundörfchen, which was a swampy fishing hamlet of Wends when the first Teutonic pioneers wandered here.

A Nuremberg astrologer once found, on consulting the stars, that the Germans discovered Leipsic on Sunday, April 16, 541 A.D., at 9.41 A.M.; but the less exact historians agree in dating this event about the year 700.

As in so many German towns, the Promenade-Ring encircles the original city, converting the ancient wall and ditch into a girdle of turf and foliage. In the Historical Museum are some mellow, enameled tiles with curious reliefs which decorated the medieval rampart. Such a transformation symbolizes the unmilitary spirit of this place of commerce and music. Although Leipsic is called „The Battle-field of the Nations“ and a huge monument is being built outside the city to commemorate the bloody victory over Napoleon in 1813, war talk is not considered good form. Soldiers are seldom seen in public, and the officer hastens into civilian garb as soon as he may. Here the musicpen has always been mightier than the sword, and the Saxons are as proud of their Church of St. Thomas as the Prussians are of their „Lion Monument“ to William I. For this plain Gothic church might almost be called the cradle of modern music. From 1723 nntil his death in 1750 Bach was its cantor and composed many of his greatest works for its services. He was director as well of the school for choristers, and even to-day it is an event to hear the boys of the Thomas School sing their Saturday motet in the old church.

Bach needed all of his creative power, for when he came, the musical resources of Leipsic consisted of four town pipers and three „art-fiddlers“ — called „Kunst Geiger,“ to distinguish them from the ordinary musician. The town pipers drew a muni- cipal salary, and their oath of office made curious reading. They swore to pipe for all church services, to sound the hours from the Rathaus tower, and to provide the music for weddings and other festivities in the Rathaus „with patience and without extortion.“ They swore not to bemean their art by piping wantonly in the street nor to sleep out of town without the permission of the mayor.

When Bach came, he complained to the authorities in an amusing letter that of the four town pipers one blew the hautboy, two the trumpet, and the fourth did not blow at all („gar nicht blast“), but fiddled first violin. Of the three „art-fiddlers“ supported by the church, one fiddled second violin. Two, on the other hand, fiddled not at all, but blew second hautboy — and bassoon. („Die beiden wiederum gar nicht geigen sondern blasen. . . .“)

Out of this chaos the master built the Gewandhaus Orchestra, which, in 1743, gave its first concert in the old Gewandhaus, or Hall of the Foreign Cloth Merchants. In 1835 young Felix Mendelssohn took up the baton and taught all Germany to love Bach, Händel, Beethoven, and Schubert. He encouraged struggling geniuses like Schumann and Gade by playing their works, and his efforts created the famous Leipsic Conservatory in 1843. To-day these concerts are given in the new Gewandhaus under the direction of Arthur Nikisch, one of the foremost of living conductors.

From every part of the city a round tower of gray stone is seen, now through a lane of old gables, or down a stretch of Ring, now backing the façades of one of the numerous squares— a mighty, rugged thing dominating the city, like an all-seeing guardian of the public weal. It is the tower of the Pleissenburg, the city's medieval citadel. The Pleissenburg was wrecked by the wars of the seventeenth century, but the old tower with a fresh top became the nucleus of the New Rathaus, the finest modern building in Leipsic, and quite worthy of its site. The great Renaissance façades are built of the French coquina with which Messel has beautified Berlin, and, new as the building is, parts of its masonry look as though they had weathered the ages and frowned down upon „the drums and tramplings of three conquests.“ Two lions of a fairly Grecian majesty ramp at the portal, the one clutching a serpent, the other throttling a limp dragon. But they perform these functions like duties, and with no vulgar, military zest. „Who could bear to imagine our city,“ writes Wustmann, a historian of twenty years ago, „without the portly tower of .its Pleissenburg and the immemorial gray of its gable-crowned Rathaus?“ Since then, alas! both have been severely „improved.“ The Old Rathaus has been taken apart and put together again, its crown of gables emerging spick and span from out their immemorial gray; while the portly neck of the Pleissenburg has received a new body and a neat copper head.

Across the river Pleisse, offsetting the spirited walls of the New Rathaus, rises the Reichsgericht, the Supreme Court of the Empire, a cool, dignified, poiseful structure, a judicial and monumental counterpart of the new Gewandhaus, the University Library, the School of Arts and Crafts, and the Conservatory, which are all huddled together in the „concert quarter.“ But for a tradesman-like economy of space these buildings might have been composed into an effective scheme. One is thankful, however, that this economy saved the Supreme Court from being overloaded with ornament in the Northern style.

Leipsic is no town of the nouveau riche. There is nothing tawdry about it; and mingled with its homely intimacy is that air of elegance and good taste to be found only among folk of breeding. The proverbial Saxon cunning which one misses in Dresden is in evidence here among the lower classes. In their lack of any striking local characteristics these Leipsickers symbolize their central position in the heart of the land. And just as Luther made the standard speech of Germany out of their official language, so they have made themselves types of the average German. The Leipsicker has known how to fuse Hessian traits with those of Würtemberg, Prussian with Bavarian, simphcity with the love of elegance, business with music and poetry and scholarship. His generous instinct for the common municipal good has made him a loyal son of the Empire. He is not so much a Saxon as a German. „There is no other great city in the land,“ writes August Sach, „that more fully represents real Germanism in its universality.“

True, Leipsic has produced such extraordinary men as Leibnitz and Wagner, and attracted to itself Bach, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Hiller, Goethe, Schiller, and Gellert. Yet the Leipsicker is an extremely normal type, and normal types seldom fail to be colorless. The folk have no great savoir-faire and are scarcely more charming than the sharp, witty, omniscient people of Berlin. But, unlike the Berliners, they do not outrage the foreign breast, for they are not malicious. They are simply colorless, like a sensible merchant who has failed to make a sale. On the whole a sturdy German conscience makes their deeds better than their words. Ask for a direction on the street, and the Leipsicker will answer indifferently, looking the other way. But five minutes later, when you have forgotten him, he will surprise you from the rear with another direction. In this ungracious way he will shadow you through the town with the best will in the world. But it is advisable not to change your mind, for he will see that you arrive at the place of first aspiration, though it take the afternoon and the police.

Characteristics so negative as the Leipsicker's may perhaps throw light on his love of music, an art which returns its devotees more spiritual stimulus than any other for a given imaginative effort.

Through its Messen, or fairs, Leipsic has become one of the most important business centers of Germany. Here crossed the two important old trade routes between Poland and Thuringia, and between Bohemia and North Germany. From Otto the Rich, Margrave of Meissen, the town obtained a monopoly of fairs, which was largely extended in 1497 by the Emperor Maximilian. These fairs grew rapidly, and came to be the largest functions of their kind in Europe. Spring and autumn the booth-filled squares were crowded with the costumes and clamorous with the tongues of all nations. Even since the advent of the railway era, the spring and autumn fairs have remained important for the trade in furs, toys, and the other goods which must be seen before being bought. But in 1906 the booths were banished outside the Frankfort Gate, and now the fair-time interest centers in the Grimmaische- and Peters- Strassen and the Neumarkt. Here the 5000 wholesale merchants have their headquarters. The houses flame with posters, and the merchants perform a sort of college-boy parade through the streets, clothed as for a masquerade ball and howling their wares to the accompaniment of every unmusical instrument known in the musician's purgatory. „A heathen scandal is that!“ confided an old Leipsicker to me.

Even more important than the fair is the booktrade, for since the middle of the eighteenth century Leipsic has been the publishing center of Germany. There are almost 1000 local publishers and dealers in printed matter; there are 190 printers; and at Jubilate 11,475 book dealers are represented in the handsome building of the Book Exchange.

This tremendous trade is due in part to the authority of the 500-year-old University on the Augustus-Platz. The venerable home of this institution was recently destroyed in a „restoration“; though in its chapel there remain some noteworthy statues, and a precious Gothic portrait of Dietzmann, the Margrave of Meissen who, in 1307, was assassinated in St. Thomas's.

The museum opposite is famous as the home of Max Klinger's Beethoven, the greatest achievement of recent German sculpture. Besides the Cranachs, a Rembrandt, and a fresco from Orvieto, there is little old art of interest. The gallery owns the original cartoons of Preller's Odyssey cycle in Weimar, and Uhde's tenderest work, „Suffer Little Children.“ There is Hartmann's whimsical bust of Schumann, and Kolbe's of Bach, both made for Leipsic's memorable music-room at the St. Louis Exposition. And there are Klinger's early experiments in colored marble — the Salome, the Cassandra, and the Bathing Girl. But the one part of indoor Leipsic that lives most vividly in my memory is the room where the pallid spirit of Beethoven dreams forever on a throne of blue and bronze and ivory.

Out of doors the most attractive part of town to me is Naundörfchen. There is something of Venice and Amsterdam and old Hamburg in the way it nestles down to the curving, canal-like river, with its charming, nondescript houses on piles. Back from the tiny cottages on the tiny river, with their glamourous windows, whence old men fish the livelong day, and with their blooming, unordered gardens full of romping children, the roofs swing tier on tier in a hundred gracious curves, with a lilt and an Old- World grace that recall the roofs of Nuremberg. A ramshackle skiff floating below Naundorfchen — that is the place to rid one's feet of the last grain of modern, metropolitan dust — that is the place to ruminate the strange history of Doctor Faustus, or to discover in some black-letter book a lyric such as this by the dusty poet Golmeyer:

Leipzic die fürnehm Handels Statt,

ein Windisch Volk erbawet hat,

welchs man Soraben hat genandt

das weit und breit worden bekandt.

Es war zwar Liptz ihr erster Nam,

den sie vom Lindenbusch bekam,

so in der Gegend g'standen ist,

wie man hiervon g'schrieben list.

(Leipsic, the stately town of trade,

Was by a Wendish people made,

A people that were Sorbs yclept,

Whose fame about the land hath crept.

Liptz was indeed its earliest name.

Which from a wood of lindens came

That stood in the vicinity,

As all the scribes of old agree.)

After the aggressiveness and modernity of Berlin, it is a relief to mingle with the quiet, matter-of-fact people of Leipsic, to rest one's eyes again on a Renaissance gable, again to loiter in streets with quaint and homely names. In many of these old names there is a flavor of poetry that brings the stranger at once into terms of intimacy with the town. They touch the imagination because they were christened naturally by the wit of the people, and always christened for their most salient feature.

Windmill Alley led in bygone days to a mill beyond the wall and ditch; along Sparrow Mountain, a thoroughfare almost as flat as Sahara, ran a prison wall, crowded winter and summer with sparrows. Begging Street pierced the slums. In Barefoot Alley was a cloister of ascetic monks, and the chivalry of the Middle Ages lived in Knight Street. „Along Milk Island“ was over against a dairy, while from Pearl-stringer Alley, Tub-maker Street, Bell- caster Street, Night-watchman Street, and Rubber Alley the corresponding occupations have not yet wholly passed away. In olden times one small lane actually bore three names simultaneously: Town Piper Alley, Constable Alley, and Midwife Alley; for these personages all dwelt there. The Brühl, called after a Slavic word for swamp, is the only street to commemorate the Wendish origin of the city and the patience of its builders; but though a few of these delightful names have passed away through sheer anachronism, enough are left to give the place an intimate, Old-World, human flavor. A city that preserves a Barefoot Alley deserves well of mankind, and I prefer small beer within its shadows to the bright new champagne of North Street.

To one who for a time had half forgotten that the larger German cities still held anything old, the Princes' House in the Grimmaische-Strasse brought a delightful shock of recognition. From those round red oriel windows flanking the gable, sixteenth-century princes used to display their finery to the folk below — student princes who came to study in the university round the corner and left their coats of arms among the carvings on the window- sills. The house is Leipsic's best example of the German Renaissance.

Through a narrow gulf of street the oldest church looks down upon this corner. The Church of St. Nicholas was built in 1017, two years after the city was first mentioned in history as Urbs Libzi. Like the later churches, it suffered many things during the sieges of the Thirty Years' War, but not so sadly as from its „restoration“ in the „Wig Time.” Then the jealous vandals of classicism, with a naivete pathetic to recall, destroyed what beauty the baroque time had spared and threw the beautiful altarpieces of Cranach into the loft where Goethe discovered them in 1815, publishing the matter with righteous wrath. They are now in the museum.

Oppo'site the gracious green of St. Nicholas's tower is a hearty, rustic kind of architecture too seldom seen in cities, a red-timbered house with piquant gables, and a carved bay-window in rococo crowned by the motto,

Ohn' Gottes Gunst all Bau'n umsunst.

(By God ungraced, all building 's waste.)

The roof, broken by little gable-windows, leads the eye onward to the vivacity of old Leipsic's sky-line —red tiles tossed into heaps and flowing together as in a choppy sea, yet with a large unity, as if composed by a modern French sculptor of the rugged school.

Next door is the gaily frescoed facade of a peasants' inn, „The Village Jug,“ with uncouth windows of glass stained in every sense, the head of a red ox serving for signboard; while over beyond the church is a Renaissance gable with three superimposed orders of classical columns, its ancient colors quite worn away. For in the sixteenth century these stone fa9ades were all painted, „mit gar kunstreichen und lustigen Gemalde gebauet und ausgeputzet,“ writes an old chronicler. (Builded and. furbished with paintings „real art-rich“ and jolly.)

Passages as narrow as those of Hamburg run through baroque courtyards to the Reichs-Strasse — the Via Imperii of the Middle Ages— one of the two principal merchant highways through the Holy Roman Empire. This is richer than the Nikolai- Strasse in such façades as the „Castle Cellar,“ with its massive, undulating gable, its flat-arched doors of worm-eaten, iron-bound wood, and its barred, diag- onal window.

From the Grimmaische-Strasse close at hand I entered a large court and warmed one of Leipsic's reticent sons gradually into garrulity.

„Look about you,“ he said. „In olden times this Hof was called 'Little Leipsic,' just as Leipsic was then called 'Little Paris.' During the fairs the costliest articles of luxury were sold here, and it was the resort of fashion. Behold!“ He pointed out a half-hidden door. „I advise you to enter. You will see the most interesting nook in town.“

I groped my way down a crooked passage into a wine-cellar the Romanesque vaulting of which, mellow with old colors, was upheld by a single pillar covered with manuscripts. I spelled out a signature. It read „J. W. von Goethe.“ On the walls were pictures of the poet, a black silhouette of his student days, a musty print of Doctor Faustus. Bewildered, I sat down and strove to conjure up a sophomoric acquaintance with „Wahrheit und Dichtung.“ Then the waiter brought a bottle labeled „Auerbach's Keller,“ and with a gasp of joy I realized that this was the immortal den where Mephistopheles once bored holes in the table and made red and white wine spurt in fountains over the good burghers. Down in an ancient sub-cellar was a fresco from the time of the Thirty Years' War. Doctor Faustus was seated, with a convivial company and quaint musical instruments, above the following inscription:

Vive, bibe, obgraecare, memor Fausti hujus et hujus

Poenae. Aderat claudo haec — ast erat ampla — gradu.

Freely rendered;

Live, drink, go to the devil; mindful of Faustus' damnation.

It had a step that was halting, but it came swiftly enough.

Another scene showed the doctor galloping out of the arched entrance on a cask accompanied by this doggerel:

Doktor Faust zu dieser Frist

aus Auerbachs Keller geritten ist

auf einem Fass mit Wein geschwind

welches gesehn viel Menschenkind

solches durch subtile Kraft gethan

und des Teufels Lohn empfing daran.

These lines might be paraphrased:

At this season Dr. Faust

Out of Auerbach's Cellar coursed

On a wine-cask running wild,

Seen by many a mother's child —

Subtle artist at his play —

And the devil was to pay.

It appears that tradition actually connected some old master of Black Art with Auerbach's Cellar, which he used as a stable, to the confusion of all honest citizens. Toward the end of the sixteenth century the tradition was transferred to the still more legendary Faustus, and in this romantic setting, more than two centuries later, the student Goethe met with the shade of his greatest hero. There is a long subterranean passage still leading from the sub-cellar to the university; and, what is even more shocking, another runs to the site of a former convent in the neighborhood.

Behind the Old Rathaus opposite is the Nasch-Markt, or Candy Market. Near a statue of Goethe stands the old exchange, an early example of the sandstone baroque that was imported from Dresden and began to flourish after the barren times of the Thirty Years' War. Much of this architecture is yet visible in the northeast corner of the Old Market and in the patrician houses of Katharinen-Strasse, the Fifth Avenue of the eighteenth century. Strangely enough, the style has almost disappeared from among the dwellings of Dresden, and now Leipsic is richer than any other large German city in private baroque architecture. Even two hundred years ago the French and Italian student journeyed hither to study this gay, new art that was transforming low, dingy rooms into spacious, brilliant halls and chambers with great windows flamboyant in fruit, flowers, leaves, and shells, and tasseled lambrequins; with portals topped by urns of plenty bulging in significant relation to the well-fed pillars below — an art evolved directly from the interior decoration of the period.

The Old Market is dominated by the Old Rathaus, a Renaissance building with many brick gables, dusky tiles, and a duskier green tower which are devoutly worshiped by every true Leipsicker. Yet somehow it lacks the atmosphere of poetry which one expects in a Rathaus of its age and traditions. It is solid, matter-of-fact, mildly pleasing, like the average citizen, and appeals little more than he to the imagination until, inside, one sees the small pillared balcony, „the pipers' chair,“ where the town pipers used to play at patrician and plebeian festivities in the days when Leipsickers loved to dance in the great hall (“ufs Rathaus tanzen“).

There is more atmosphere about the house on the Brühl where young Goethe used to court his Gretchen, the awakener of his genius; and, significantly enough, on Kätchen Schönkopf's roof a well-weathered Apollo stands above Romanesque gateways and gratings, pointing toward heaven. The Brühl is a distinguished street. At Number 3 I entered, walking between rails into a Hof full of trucks and meal. And, set in a wall of brick and cement, was a simple tablet with the inscription:

In this house was born

Richard Wagner

May 22, 1813

On a hillock, perched above a picturesque line of roofs, the Church of St. Matthew is grateful to eyes wearied with the levelness of Leipsic. Here as in all flat lands every elevation is cherished, and an almost imperceptible rise in the Promenade-Ring, famous for its view of the New Rathaus, has been popularly christened the Promenade Wart. Indeed, in seeking the Schiller House in Gohlis, I was directed “bergauf” (literally, „up the mountain“) along a road where the rain-water was standing in pools. The site of St. Matthew's is more remarkable than its architecture, for the church is based on the ruins of Leipsic's first citadel, and looks over across the Pleisse to little Naundörfchen, which was a swampy fishing hamlet of Wends when the first Teutonic pioneers wandered here.

A Nuremberg astrologer once found, on consulting the stars, that the Germans discovered Leipsic on Sunday, April 16, 541 A.D., at 9.41 A.M.; but the less exact historians agree in dating this event about the year 700.

As in so many German towns, the Promenade-Ring encircles the original city, converting the ancient wall and ditch into a girdle of turf and foliage. In the Historical Museum are some mellow, enameled tiles with curious reliefs which decorated the medieval rampart. Such a transformation symbolizes the unmilitary spirit of this place of commerce and music. Although Leipsic is called „The Battle-field of the Nations“ and a huge monument is being built outside the city to commemorate the bloody victory over Napoleon in 1813, war talk is not considered good form. Soldiers are seldom seen in public, and the officer hastens into civilian garb as soon as he may. Here the musicpen has always been mightier than the sword, and the Saxons are as proud of their Church of St. Thomas as the Prussians are of their „Lion Monument“ to William I. For this plain Gothic church might almost be called the cradle of modern music. From 1723 nntil his death in 1750 Bach was its cantor and composed many of his greatest works for its services. He was director as well of the school for choristers, and even to-day it is an event to hear the boys of the Thomas School sing their Saturday motet in the old church.

Bach needed all of his creative power, for when he came, the musical resources of Leipsic consisted of four town pipers and three „art-fiddlers“ — called „Kunst Geiger,“ to distinguish them from the ordinary musician. The town pipers drew a muni- cipal salary, and their oath of office made curious reading. They swore to pipe for all church services, to sound the hours from the Rathaus tower, and to provide the music for weddings and other festivities in the Rathaus „with patience and without extortion.“ They swore not to bemean their art by piping wantonly in the street nor to sleep out of town without the permission of the mayor.

When Bach came, he complained to the authorities in an amusing letter that of the four town pipers one blew the hautboy, two the trumpet, and the fourth did not blow at all („gar nicht blast“), but fiddled first violin. Of the three „art-fiddlers“ supported by the church, one fiddled second violin. Two, on the other hand, fiddled not at all, but blew second hautboy — and bassoon. („Die beiden wiederum gar nicht geigen sondern blasen. . . .“)

Out of this chaos the master built the Gewandhaus Orchestra, which, in 1743, gave its first concert in the old Gewandhaus, or Hall of the Foreign Cloth Merchants. In 1835 young Felix Mendelssohn took up the baton and taught all Germany to love Bach, Händel, Beethoven, and Schubert. He encouraged struggling geniuses like Schumann and Gade by playing their works, and his efforts created the famous Leipsic Conservatory in 1843. To-day these concerts are given in the new Gewandhaus under the direction of Arthur Nikisch, one of the foremost of living conductors.

From every part of the city a round tower of gray stone is seen, now through a lane of old gables, or down a stretch of Ring, now backing the façades of one of the numerous squares— a mighty, rugged thing dominating the city, like an all-seeing guardian of the public weal. It is the tower of the Pleissenburg, the city's medieval citadel. The Pleissenburg was wrecked by the wars of the seventeenth century, but the old tower with a fresh top became the nucleus of the New Rathaus, the finest modern building in Leipsic, and quite worthy of its site. The great Renaissance façades are built of the French coquina with which Messel has beautified Berlin, and, new as the building is, parts of its masonry look as though they had weathered the ages and frowned down upon „the drums and tramplings of three conquests.“ Two lions of a fairly Grecian majesty ramp at the portal, the one clutching a serpent, the other throttling a limp dragon. But they perform these functions like duties, and with no vulgar, military zest. „Who could bear to imagine our city,“ writes Wustmann, a historian of twenty years ago, „without the portly tower of .its Pleissenburg and the immemorial gray of its gable-crowned Rathaus?“ Since then, alas! both have been severely „improved.“ The Old Rathaus has been taken apart and put together again, its crown of gables emerging spick and span from out their immemorial gray; while the portly neck of the Pleissenburg has received a new body and a neat copper head.

Across the river Pleisse, offsetting the spirited walls of the New Rathaus, rises the Reichsgericht, the Supreme Court of the Empire, a cool, dignified, poiseful structure, a judicial and monumental counterpart of the new Gewandhaus, the University Library, the School of Arts and Crafts, and the Conservatory, which are all huddled together in the „concert quarter.“ But for a tradesman-like economy of space these buildings might have been composed into an effective scheme. One is thankful, however, that this economy saved the Supreme Court from being overloaded with ornament in the Northern style.

Leipsic is no town of the nouveau riche. There is nothing tawdry about it; and mingled with its homely intimacy is that air of elegance and good taste to be found only among folk of breeding. The proverbial Saxon cunning which one misses in Dresden is in evidence here among the lower classes. In their lack of any striking local characteristics these Leipsickers symbolize their central position in the heart of the land. And just as Luther made the standard speech of Germany out of their official language, so they have made themselves types of the average German. The Leipsicker has known how to fuse Hessian traits with those of Würtemberg, Prussian with Bavarian, simphcity with the love of elegance, business with music and poetry and scholarship. His generous instinct for the common municipal good has made him a loyal son of the Empire. He is not so much a Saxon as a German. „There is no other great city in the land,“ writes August Sach, „that more fully represents real Germanism in its universality.“

True, Leipsic has produced such extraordinary men as Leibnitz and Wagner, and attracted to itself Bach, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Hiller, Goethe, Schiller, and Gellert. Yet the Leipsicker is an extremely normal type, and normal types seldom fail to be colorless. The folk have no great savoir-faire and are scarcely more charming than the sharp, witty, omniscient people of Berlin. But, unlike the Berliners, they do not outrage the foreign breast, for they are not malicious. They are simply colorless, like a sensible merchant who has failed to make a sale. On the whole a sturdy German conscience makes their deeds better than their words. Ask for a direction on the street, and the Leipsicker will answer indifferently, looking the other way. But five minutes later, when you have forgotten him, he will surprise you from the rear with another direction. In this ungracious way he will shadow you through the town with the best will in the world. But it is advisable not to change your mind, for he will see that you arrive at the place of first aspiration, though it take the afternoon and the police.

Characteristics so negative as the Leipsicker's may perhaps throw light on his love of music, an art which returns its devotees more spiritual stimulus than any other for a given imaginative effort.

Through its Messen, or fairs, Leipsic has become one of the most important business centers of Germany. Here crossed the two important old trade routes between Poland and Thuringia, and between Bohemia and North Germany. From Otto the Rich, Margrave of Meissen, the town obtained a monopoly of fairs, which was largely extended in 1497 by the Emperor Maximilian. These fairs grew rapidly, and came to be the largest functions of their kind in Europe. Spring and autumn the booth-filled squares were crowded with the costumes and clamorous with the tongues of all nations. Even since the advent of the railway era, the spring and autumn fairs have remained important for the trade in furs, toys, and the other goods which must be seen before being bought. But in 1906 the booths were banished outside the Frankfort Gate, and now the fair-time interest centers in the Grimmaische- and Peters- Strassen and the Neumarkt. Here the 5000 wholesale merchants have their headquarters. The houses flame with posters, and the merchants perform a sort of college-boy parade through the streets, clothed as for a masquerade ball and howling their wares to the accompaniment of every unmusical instrument known in the musician's purgatory. „A heathen scandal is that!“ confided an old Leipsicker to me.

Even more important than the fair is the booktrade, for since the middle of the eighteenth century Leipsic has been the publishing center of Germany. There are almost 1000 local publishers and dealers in printed matter; there are 190 printers; and at Jubilate 11,475 book dealers are represented in the handsome building of the Book Exchange.

This tremendous trade is due in part to the authority of the 500-year-old University on the Augustus-Platz. The venerable home of this institution was recently destroyed in a „restoration“; though in its chapel there remain some noteworthy statues, and a precious Gothic portrait of Dietzmann, the Margrave of Meissen who, in 1307, was assassinated in St. Thomas's.

The museum opposite is famous as the home of Max Klinger's Beethoven, the greatest achievement of recent German sculpture. Besides the Cranachs, a Rembrandt, and a fresco from Orvieto, there is little old art of interest. The gallery owns the original cartoons of Preller's Odyssey cycle in Weimar, and Uhde's tenderest work, „Suffer Little Children.“ There is Hartmann's whimsical bust of Schumann, and Kolbe's of Bach, both made for Leipsic's memorable music-room at the St. Louis Exposition. And there are Klinger's early experiments in colored marble — the Salome, the Cassandra, and the Bathing Girl. But the one part of indoor Leipsic that lives most vividly in my memory is the room where the pallid spirit of Beethoven dreams forever on a throne of blue and bronze and ivory.

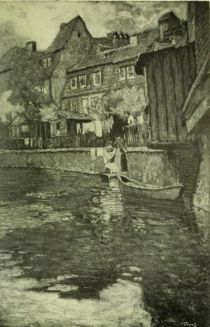

Out of doors the most attractive part of town to me is Naundörfchen. There is something of Venice and Amsterdam and old Hamburg in the way it nestles down to the curving, canal-like river, with its charming, nondescript houses on piles. Back from the tiny cottages on the tiny river, with their glamourous windows, whence old men fish the livelong day, and with their blooming, unordered gardens full of romping children, the roofs swing tier on tier in a hundred gracious curves, with a lilt and an Old- World grace that recall the roofs of Nuremberg. A ramshackle skiff floating below Naundorfchen — that is the place to rid one's feet of the last grain of modern, metropolitan dust — that is the place to ruminate the strange history of Doctor Faustus, or to discover in some black-letter book a lyric such as this by the dusty poet Golmeyer:

Leipzic die fürnehm Handels Statt,

ein Windisch Volk erbawet hat,

welchs man Soraben hat genandt

das weit und breit worden bekandt.

Es war zwar Liptz ihr erster Nam,

den sie vom Lindenbusch bekam,

so in der Gegend g'standen ist,

wie man hiervon g'schrieben list.

(Leipsic, the stately town of trade,

Was by a Wendish people made,

A people that were Sorbs yclept,

Whose fame about the land hath crept.

Liptz was indeed its earliest name.

Which from a wood of lindens came

That stood in the vicinity,

As all the scribes of old agree.)

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

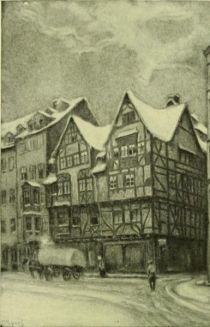

Leipsic — An Old House in the Nikolai-Strasse. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

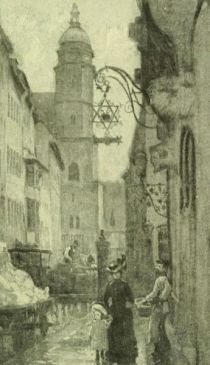

Leipsic — St. Thomass from the Burg-Strasse. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

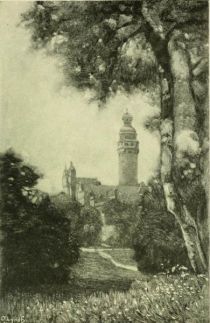

Leipsic — The Old Rathaus. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Leipsic — The New Rathaus from the Promenade-Ring. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Leipsic — On the Pleisse, in the Naundorfchen Quarter. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

alle Kapitel sehen