VI Hildesheim and Fairyland.

Few of the older German cities, like Goslar and Lübeck, show themselves at once to the traveler for what they are. As a rule, like Danzig, Bautzen, and Augsburg, they are coy and cover their charms with a cheap new veil. But of these, none is coyer than Hildesheim. Of course I did not expect the railway station to be romantic. But my hotel window, near by, gave on the town, and one glance brought a pang of disappointment. Almost the first sound I had heard on arrival was the clatter of a pianola brutally enlivening a cinematograph show; and now the first glimpse of the home of the Thousand-year Rose-bush was of an ordinary New England village with its deadly commonplace houses and its homely steeples.

A few steps tbward the center of things destroyed this disillusion, only to bring another. I had expected to find Hildesheim a smaller, more exquisite edition of my favorite German city — a little Brunswick de luxe with a jeweled clasp. Instead I found its counterpart, and within the next few hours was forced to reconstruct all my ideas of the place.

Brunswick is democratic, a city of plain people. Hildesheim is aristocratic, as befits the ancient see of a line of great prelate princes. Brunswick's charm is mainly Gothic; Hildesheim's, mainly Romanesque and Renaissance. There the churches are subservient to the wonderful, homogeneous old streets about them; the houses are sincere expressions of strong individuality. Here the real key-note of the place is struck by such magnificent church interiors as St. Michael's and St. Godehard's. Many of these houses are richer, more picturesque than those of Brunswick, but the rich facades are in glaring contrast to the poorer ones, and often show, instead of personal initiative, a desire to emulate the pomp, the learning, the solemn circumstance of the bishops. In Hildesheim there is a marked absence of the familiar, informal little courts, the grotesque friezes, the homely, humorous carvings and niottos that make Brunswick such an intimate place. Inscriptions are there a-plenty, but most of them are pompous or stilted, ill-natured, didactic, or melancholy, and a great many are in ostentatious Latin. It is clear that the old Hildesheimers were not so happy in their exclusiveness as were the Brunswickers in their democracy. Instead of the genial clowns and mermen, the tugs of war, the musical asses and apes, the domesticated gargoyles, behold reliefs of the Virtues and the Vices, of the Arts, Sciences, Elements, Seasons, — all with neat Latin labels that remind one of the scrolls issuing from the mouths of figures in old-fashioned woodcuts. And the few saints left over from Gothic times keep shockingly indiscriminate company, not with Low-German sinners, but with the gods of Greece and Rome. I have known no other private architecture with so strong a didactic and homiletic flavor as that which these Hildesheimers assimilated from their pious overlords.

But if the place gives one the impression of being always on her good behavior and a trifle self-con- scious, she more than makes up for it by her wealth of legend. Fairy fingers have woven gleaming strands about many of her choicest treasures, and in the length and breadth of the German land there are few legends more lovely than that of the origin of Hildesheim. This is one of the many variants:

In the year 815, Emperor Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, was hunting in the outskirts of the Hercynian forest, and, in following a white buck, he outdistanced his followers and lost both his quarry, his horse, and his way in the Innerste River. The Emperor swam to shore and wandered alone until he came to a mound sacred to the ancient Saxon goddess Hulda — a beautiful mound covered with her own flower, the wild rose. Again and again he sounded his hunting-horn, but there was no answer. Then he drew from his bosom a casket containing relics of the Holy Virgin, and, while praying before it for rescue, fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke the mound where he lay was covered with snow, although it was high summer and everything about was green. The roses on the sacred mound were blooming more brilliantly than ever. He looked for the reliquary and found it frozen fast amid the thorns of a great rose-bush. Then the Emperor knew that the heathen goddess had, „by shaking her bed,“ sent the holy snow in token that the Christian goddess should now be worshiped in her stead. „When his followers finally discovered him he had resolved to build on that mound a cathedral to the Virgin Mary. And to-day on the choir of this cathedral that very rose-bush is still in bloom.

All this is by no means a pure fiction. For it is certain that the spot was a headquarters of the old Saxon religion; that Louis transferred the Eastphalian see here from Elze in 815; and that nobody knows how many centuries old the roots of the famous rose-bush really are. Where it grows is the birthplace of Hildesheim, a name thought to mean „Hulda's Home,“ and the old cloisters that inclose it are worthy of their situation. In the autumn, when their smothering of woodbine breaks forth into scarlet and old rose and carnelian, into all pinks and oranges and purples— brought out the more by the deep browns and grays and yellows of the double arcade — it needs neither the Thousand-year Rosebush, nor the crumbling tombs, nor the charming Gothic chapel, with its devout gargoyles, that is set in the midst, to make this cloister garden one of the sweetest shrines ever dedicated to the contemplative life.

Out of this beautiful beginning grew a city that has, ever after, seemed suffused with the romaunt of the rose. The first small, fortified settlement about the cathedral, called the Domburg, was surrounded with rose-hedges which became the godmothers of such streets as Long-hedge, Short-hedge, Flood-hedge, and the trio of Rose-hedges (Rosenhagen I, II, and III). And there is a tradition that each of the cathedral clergy is warned of his own death three days beforehand by a white rose which he finds in his choir-stall.

In the eighteenth century, sad to relate, the ancient, austere splendor of the cathedral interior was transformed into a baroque splendor that shows particularly tawdry and frivolous against the few remains of Romanesque construction and the notable treasures of early art that fill the building. Though the architecture of this cathedral is not to be compared with Brunswick's, yet the place is fully as interesting. For here the famous bronze doors, the Christ Pillar, and the font far outshine the trinity of Romanesque sculptures there.

The bronze doors were finished in 1015 by St. Bernward of Hildesheim, one of the most illustrious of German bishops, celebrated as teacher, architect, sculptor, and friend of three emperors. Standing before them, one is filled with astonishment on remembering that this was the virgin appearance of art in a region hitherto artless. It is a miracle of precocity. For these reliefs, though crude, are far more direct and elemental, and touch the heart more deeply, in their naive blend of humor and pathos and religious fervor, than Ghiberti's doors on the Florentine baptistery.

During his visit to Rome in the year 1001, St. Bernward borrowed his main idea from the doors of St. Sabina; and his Christ Pillar was executed in the spirit of the Column of Trajan.

It is peculiarly fitting that these works, representing the miraculous birth of German art, should be accompanied by the thirteenth-century font that stands for the culmination of Romanesque brazen sculpture in the North.

In the nave hangs a reminder of that Bishop Hezilo who urged on his bloody band from the high altar of Goslar. It is an immense chandelier in the form of the heavenly Jerusalem, a battlemented ring-wall of exquisite filigree broken by twelve towers and twelve portals.

Before the elaborate Renaissance reredos stands a column of polished stone bearing a Madonna. The people of Hildesheim firmly believe it to be a part of the original Irmensaule that stood near the city in the Dark Ages and marked the principal shrine of the Old Saxon god Irmin. They say that Charlemagne cast it down and broke it with his own hand in his vigorous attempt to Christianize the heathen — a conception inhumanly abused by certain German professors who have an almost puritanical hatred of the glamourous and force every attractive idea to stand trial for its life. In their despite I prefer to believe that this is the authentic heathen pillar, and that the relics of the Virgin were really frozen by the sacred snow in the rose-bush outside, more than a millennium ago.

At any rate, one may see in the treasury the very reliquary that contained those relics, besides many other precious things, such as the gemmed fork of Charlemagne, a sliver of the true cross, the head of Oswald, King of Northumbria, who died in the year 642, the geometry from which the holy Bernward taught Emperor Otto III. And all at once you come upon a thing that transports you in a trice beyond the Alps into the hush of another holy treasure- house below the hill of Fiesole. It is a perfect Uttle altar by Fra Angelico.

Worn out by the incessant demands of so much beauty, I left the building to rest for an hour on the smooth lawns, beneath the venerable lindens of the Domhof. The treasury had taken me to „the warm South“; but here for the first time on my pilgrimage I caught a breath of the peaceful seclusion, the idyllic secret charm of the English cathedral close.

A citizen came to sit beside me and to relate how, in that very place, until the middle of the eighteenth century, the boys of Hildesheim had annually played at Charlemagne and the Heathen, a game in which the Irmensäule in effigy was finally stoned and overthrown.

The old gentleman pointed to the gilded cathedral cupola that sheltered the old heathen pillar. „That also has a story,“ he said. „In the year 1367 the Brunswickers surprised us in overpowering numbers. Then good Bishop Gerhardt put himself at the head of our little army and prayed to the Holy Virgin. 'It is for thee to decide now whether thou wilt live henceforth under a roof of thatch or of gold.' As our men approached the great host of Brunswick, they were dismayed but the Bishop stretched forth his left arm, crying, 'Leven Kerle, truret nich, hier hebbe ek noch dusend in miner Maven.' ('My dear fellows, be not dismayed. I have here a thousand more [men] up my sleeve.') Then they knew that the good bishop carried in his sleeve Hildesheim's greatest treasure, the reliquary of the Virgin, and, taking heart, they put the enemy to rout, slaying fifteen hundred of them and capturing rich spoils. Ever since,“ the old gentleman concluded, „our dear Lady has lived under a golden roof.“

Not far from this quiet close I found another feast of beauty.

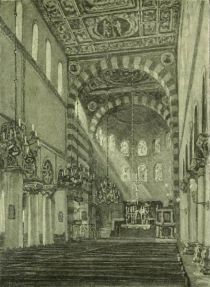

The lawns and gardens surrounding the Church of St. Michael meant renewed thoughts of old England, and the interior brought back like a refrain the holiest memories of Italy. For though the Romanesque is more truly the national style of Germany than any other, yet this most perfect of Northern Romanesque interiors cannot help suggesting the land of its birth. The alternation of light and dark blocks in the transept arches reminds one of Siena, while the pure beauty and variety of the capitals take one back to Ravenna. These capitals pass from the simple „dice“ design of the year 1000 to the timid attempts at low relief of the middle, and the high relief of the end of the eleventh century, with grotesques and even medallions between the angel corners. These, in turn, pass into the luxuriant stone foliage of the twelfth century, peopled with little faces and figures.

It pays to prowl long in St. Michael's, for there is many a surprise in store for the appreciative, such as the eight archaic beatitudes over the columns of the southern aisle, with their hint of Assyrian influence; or the delightful angels and saints on each side of the wall separating the western choir from the northern transept; the tombs, the altarpieces, and the crypt where Bernward reposes and shows himself even here for the saint and artist that he was by the flowing Latin hexameters of his own epitaph. It is a satisfaction to know that he made his famous doors and Christ Pillar for this sanctuary, and that they have not, until recent years, been compelled to endure the baroque cathedral interior.

St. Michael's crowning glory is the painted wooden ceiling of 1180, the only one of its kind north of the Alps. It gives the genealogy of Christ from Adam down, with a feeling for composition, a restraint, and a knowledge of anatomy quite unusual in Romanesque painting. And there is a touch, too, of the Germany we know. For if you look long enough you discover that the tree back of Eve is filled with portraits of the five senses, while in Adam's tree reposes the Herrgott himself — a conception truly German in its lack of gallantry.

It is an uncanny experience to be dreaming alone in this church and to be roused by a sudden chorus of horrible laughter and heartrending shrieks from the insane in the adjoining cloisters, which are now used as an asylum. And it is even more distressing to visit the cloisters and see the poor souls hurrying about distractedly among the foliage and flowers, without the least appreciation for the lovely arcades and portals where the late Romanesque is so happily fused with the early Gothic.

The Church of the Magdalene is worth visiting for the sake of its three treasures: a jeweled cross containing splinters of the true cross, and a pair of wonderful candlesticks, all the work of Bernward and prophetic of the Renaissance goldsmiths of Nuremberg.

It is not often that one city possesses two leading examples of the same architectural style. But St. Godehard's is one of St. Michael's dearest rivals and even surpasses the sister church in the purity and homogeneity of its ornament, though it has recently been disfigured by a great deal of garish paint. It has, besides, an interesting portal and a precious little treasury.

The Church of the Cross is one of those fascinating churches that are coming more and more to light in our day— churches built originally to war not against spiritual wickedness, but against flesh and blood. For the Kreuz Kirche was originally an outwork of the Bishop's Fortress on Cathedral Hill. And the chronicler Saxo records that toward the end of the eleventh century Bishop Hezilo changed it from a home of war (domum belli) to a home of peace (domum pacis) — a transformation even more commendable than that of swords into plowshares. May this act not have been in expiation of Hezilo's share in the „Blood-bath“ at Goslar?

The town halls of Hildesheim and of Brunswick neatly contrast the spirit of the two places. The low, level Rathaus of democratic Brunswick is faced with a series of ten double arcades, all free and equal. Hildesheim's Rathaus sounds a note unmistakably aristocratic, with its commanding western gable flanked by proud clock- and window-towers.

The interior at Brunswick is plain; here it is resplendent. And it is a significant fact that the fine frescos of local history and legend, begun by Prell in 1887, were the pioneers of the recent German revival of the old al fresco technique. The building teems with legend.

On the apex of the western facade the Hildesheimer Jungfer, the Maid of Hildesheim, stands proudly under a baldachin. She is supposed to be no other than the old heathen goddess who sent the sacred snow, and who once, in the form of the Holy Virgin, appeared to a maiden lost in the woods beyond the wall and led her back to her home. She it was who used to stand on the ramparts in time of siege and catch the cannon-balls of the foe in her apron. So that, out of gratitude, the Hildesheimers graved her image on their municipal banner and seal.

On the clock-tower, below the red-frocked town piper, who pipes the halves and trumpets the hours, is the head of a Jew who opens and closes his eyes and mouth at the sound of the trumpet, as if in pain at the thought of another unprofitable hour gone by. They call it the head of a would-be traitor who was caught in the fact and shut in the Rathaus dungeon to die of starvation.

In the northern wall a measure is chiseled, with these words: „Dat is de Garen mathe.“ („This is the measure for yarn.“) You are told that the widow of a local yarn-dealer was once wakened by her late spouse, who complained bitterly that he had to suffer so much pain in his present home because, in life, he had bought with a long measure and sold with a short one. Whereupon he cast an iron ruler upon the table, crying, „Dat is de Garen mathe!“ and vanished. When the widow came to her senses the ruler had disappeared, but the measure was burned through the table, through all the floors of the house, and so deep beneath the cellar that the bottom of the hole could not be plumbed. Then the magistrate graved the length of the measure upon the wall of the Rathaus as an abiding stimulus to honesty. It is possible that the moral reaction after this incident inspired the rather optimistic inscription on the Kramergildehaus in the Andreas-Platz:

Weget recht un glike,

So werdet gi salich un ricke.

(Weigh justly and equally, which

Will make you happy and rich.)

What draws most of us, after all, to Hildesheim is not the lure of its churches and public buildings, potent as it is; but rather the lure of the quaint streets and squares, and of the houses where German private architecture touches its zenith. Though these distinguished dwellings are not jolly and intimate like Brunswick's, they are more glamourous. These narrow, „Haufendorf“ streets disengage no least hint of Brunswick's democracy, but they are the abiding-places of romance. And, touched by the shadow of these strange, rich façades, the traveler peers instinctively into every coach that clatters by for a glimpse of the fairy godmother with her magic wand, of the little kobold with the wishing-ring for the first who may befriend him, or of an authentic local sprite like Hütchen of the large hat, or Huckup the bogy-man of Hildesheim, whose statue is under the big tree in the Hoher Weg. Nor is this curiosity unjustifiable. For what has happened may happen; and Hildesheim has, in its day, supplied the stuff for many a fairy-tale. There is, for example, the true story of the Little Princess:

Once upon a time there came to Bakermaster L — in the Goschen-Strasse a beautiful maiden begging for work. The old man put on his spectacles, noted her delicate features and soft hands, and sent her about her business. „Thank heaven,“ he cried, „that we no longer need a nurse-maid! Now if you were only the sort to do heavy barn and field work we might give you a trial.“

The maiden wept bitterly, protesting that nothing worthy a servant was foreign to her nature. So the kind-hearted baker consented to try her.

She was a decided success. The cows were kept as soft and sleek as cats, and no man could keep up with her in the field. So that the old couple were charmed and loved her as their own daughter.

When the neighbors dropped in of an evening to discuss the hard times and the war over a mug and a pipe, the maiden, who sat by at the spinning-wheel, would often join in and talk of emperors and kings as though she were quite at home with such folk. Then some one would speak up:

„Maiden, you seem to know the world well. Where, then, do you come from?“

But she would only heave a deep sigh and moisten her flax with her tears.

There was one old fellow who liked to pinch her rosy cheeks when no one was looking and call her the Little Princess. And presently the whole neighborhood took up the name.

One morning the baker's farm-wagon was unloading before his portal, and the Little Princess was so busy with her pitchfork that she did not hear the cries and huzzas that suddenly burst forth around her. The whole Goschen-Strasse was so packed with folk that an apple could n't have fallen to the ground (dass kein Apfel mehr zur Erde konnte).

A company of gold-laced lackeys made way with their silver drum-majors' sticks for a great float filled with more than a hundred Moors and apes who rent the air with trumpet and drum.

Only the Little Princess labored on and took no notice.

Finally came a golden coach-and-six. A beautiful knight, clad in gold and silver, sprang out, caught the Little Princess in his arms, and exclaimed: „Ah, my heart's love, Marianne, our time of probation is over! The Kaiser has been beaten, and we may now be married!“

The lackeys sprang to lift her into the coach.

„But,“ protested the Little Princess, „only see how I look! Let me first change my dress.“

„Nay, nay!“ cried the prince, proudly. „This dress we will keep forever as a memento.“

Then the prince threw the astonished bakermaster a great purse of gold, and they vanished amid the acclamations of the populace.

Though the Goschen-Strasse is one of the plainest streets in town, one glance at it will convince any skeptic that this story is true. Such things happen inevitably in such a setting. And in wandering through the richer streets one's imagination is positively overpowered with all the surprising and lovely events that have, or ought to have, taken place there. It is like walking bodily through the pages of Grimm.

In our day it is the mode to shrug one's shoulders at the German Renaissance. And, indeed, what with the tenacity of its predecessor the Gothic, and the untimely disaster of the Thirty Years' War, the style had small chance to mature in the Fatherland.

But no one who knows such places as Hildesheim and Nuremberg, Danzig and Rothenburg— towns especially spared in the great war— can feel like scoffing at the German Renaissance. For there the style makes up in picturesqueness for its departure from the canons of Italian proportion. It is like the young poet at college who abjures conic sections to go in for literature and music. Its faults are simply the extravagances of romantic youth. For the German Renaissance is, at its best, eternally young and eternally romantic.

It must have been a dim realization that this fresh charm scarcely befitted their proud, pious aristocracy that made the Hildesheimers try to counteract its effect with solemn, pompous, pedantic carvings and inscriptions.

The „Old-German House,“ for instance, at the head of the Oster-Strasse is a delightful composition of three sharp gables with a great bay-window as high as the roof and four tiers of wooden friezes, inimitable at a distance. But these turn out to be representations of the elements and the heavenly bodies, and prominent among them is Death with a youth, a sage, and this motto:

Hodie mihi — cras tibi.

(To-day for me — to-morrow for thee.)

These wide, lofty bays are as characteristic of Hildesheim as small, delicate oriels are of Nuremberg. And it would be hard to decide which kind is the more picturesque. There are two fine bays in the Wedekind House in the Markt, with a seven-storied gable rising between them. The whole house is overspun with filigree like one of the elaborate reliquaries in the cathedral, with an effect indescribably vivacious. But these, floor by floor, are the subjects of the carvings:

I. Truth, Justice, Charity, Hope, Wealth, Prudence, Fortitude, Courage, Temperance, Patience, Faith.

II. Grammar, Dialectics, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Music, Woman with Pitcher and Glass, Geometry, Woman with Soap-bubble, Astrology.

III. A Tower (earth), A Ship (water), A Thunderbolt (fire). Avarice, Air, Sloth, Woman with Pitcher, Pride, Luxury, Appetite, Envy, Wrath.

Even the kind ladies with pitchers, there doubtless to moisten these dry abstractions, must have appeared with the sanction of those ecclesiastics who opened Hildesheim's first saloon under the auspices of the cathedral.

There are many pious inscriptions, such as:

Affgunst der ludc kann dich nicht schaden,

was Godt will das muss geraden.

(Man's malice cannot injure you;

What God intends that must go through.)

Here is a hint of the truculent, misanthropic note that reechoes constantly in the inscriptions of these aristocrats and would-be aristocrats.

The Wedekind House shows the more elaborate and nervous by contrast with the dignified Gothic „Temple House“ next door, with its narrow, trefoiled windows, its great spaces of repose, and the loopholed watch-turrets on each side.

And the Roland Fountain before them helps to harmonize the two houses, combining as it does the decorativeness of the one with the nobility and calm of the other.

Across the Markt is a corner which every lover of Germany holds as a hallowed spot. Here stands the Butchers' gildhouse — the Knochenhaueramtshaus — famed as the finest half-timbered building in the land. It is a splendid specimen of the early Renaissance, and, through its model in the leading museums, the world has come to love the rhythmical proportions of its baldly projecting stories, its sharp, lofty gable, its purely modeled corbels and friezes. So that its partial destruction by fire in 1884 was mourned as an international calamity. Through this fire one of the mottos on the eastern façade was given a lamentable architectural application:

Arm und reich,

Der Tod macht Alles gleich.

(For poor and rich the sequel

By Death is brought out equal.)

But the house has been splendidly restored.

It would be useless to attempt describing within these limits allpf the most fascinating among the four hundred noteworthy old houses of Hildesheim. It must suffice merely to mention a few types.

On the corner where one comes to the Hoher Weg is the Ratsapotheke, with its long-winded Latin hexameters and German doggerel and with one of Hildesheim' s few fine Renaissance portals. Farther on is the old Ratsweinschenke, with solemn biblical illustrations of the wine business such as the Noah episode and the spies importing grapes from the Promised Land.

The Hildesheimers liked to copy the architecture as well as the customs of their friends the fairies. The fa9ade of the Kaiserhaus is a thing as curiously inverted as a „goop.“ For the elaborate stone oriel and portal reproduce the wood-carver's technique so well that thej'- seem petrified, and the expanse of wall filled with medallions of Roman emperors seems as if copied from some rich ceiling of paneled oak.

These people were fond of building toy streets like the Hoken and the Juden-Strasse — streets almost as narrow as the narrowest Venetian lanes; streets whose houses, set capriciously askew, almost allow opposite neighbors to shake hands from their projecting stories.

They delighted in toy houses like the little one in the Andreas-Platz, set perpendicular to the sharply sloping street; or the Pillar House, under which the way leads into the square. This beautiful dwelling is a veritable picture-book of the Virtues, the Muses, and the gods of Rome. One unconsciously expects these wooden people to come alive all of a sudden, like the gingerbread children on the witch's house in „Hänsel und Gretel.“ It might well have really been a witch's house; for many such old persons have been done to death in Hildesheim. There is only one thing to spoil its delightful atmosphere. It is that self-conscious quotation about mens conscia recti.

The Hildesheimers were fond of composing an amusing line of roofs such as the one northeast of St. Andrew's, and of leaving one grand old Gothic house (like Trinity Hospital) to temper the vivacity of a Renaissance neighborhood like an ancient oak set in a grove of silver birches.

They were fond of packing alleys full of romantic, strangely formed gables, and winding them alluringly away into the unknown as they wound the Eckemecker-Strasse away from the dominating tower of St. Andrew's. This street name is onomatopoetic; for, with its suggestion of bleating flocks, it means „The Street of Sheepskin Tanners.“ It is a name fitter for laughing Brunswick than for longfaced Hildesheim. Here stands one of the most fascinating houses in town, the Roland Hospital, with its tall, characteristic bay and its five far-projecting stories adorned with scenes from the former rural life of Simon Arnholt, its builder, such as sheep- shearing, hunting, wine-making, pig-sticking, sowing, and sandbagging the police. At least, I thought them police at first, but found later that they were only Philistines being smitten with the jaw-bone of an ass. And there is an inscription with the same old note of defiance, as though whoever built a fine house in this place had to become a mark for envious tongues:

Wer bawen will an freier strassen,

muss sich vel unnütz geswetz nich iren lassen.

(He who would build upon the public walk

Must not be turned aside by idle talk.)

The Schuh-Strasse runs parallel to the Eckemecker- Strasse and, in the matter of picturesqueness, is a worthy companion. But you will find more noteworthy houses by turning down the Bohlweg — which derives its name from the planks, or Bohlen, laid down in olden times for crossing the marshy remnants of the cathedral moat. Here, at the head of the Kreuz-Strasse, is the Domschenke, or Cathedral Wine-house; and opposite is its first rival, the Golden Angel, a charming early Renaissance building called „Der Alte Schaden“ (The Old Damage), because it damaged the monopoly of the Domschenke. It bears a relief of five horses straining at three wine-butts; and behind them appears mine host solemnly reckoning up his gains.

Not many doors down the Kreuz-Strasse is the tavern called „Der Neue Schaden“ (the New Damage), the second rival. And a serious rival it was; for it introduced into Hildesheim that pale amber fluid which was destined never to check its mad career until it became the national drink. This fine transition façade actually bears humorous carvings.

„Fish-tailed persons,“ writes learned Herr Gerland, „are drinking there and experiencing all the effects of drinking, while heads, interposed, reflect the impressions which are produced upon them by these phenomena.“

No wonder the New Damage was so daring as to be humorous, for that jolly tavern was always the hotbed of radicalism. And in Luther's time it was the headquarters of the Reformation Club, which used to make it a base of supplies in their horse-play campaigns against the old-fogy Catholics. It is easy to imagine what these zealous youths must have done to the Reformation chronicler Johannes Oldecop, Dean of the Holy Cross. For, upon the façade of his house around the corner, the old gentleman poured out all his bitterness against the new faith. His fury may be seen even in the jumbled order of the words, which read like a Chinese puzzle:

Anno dm. 1549. Virtus, ecclesia. clerus demon, simonia. cessat. turbatur. errat. regnat. dominatur. verbum dni manet in eternum nil nisi divinum stabile, humana laborant, lignea cum saxis sunt peritura

(a.d. 1549. Virtue ceases, the church is in an uproar, the clergy has gone astray, the devil rules, simony reigns. God's word remains for all eternity. The divine alone stands. The human is in peril. Wood and stone will pass away.)

Past the Square of the Holy Cross, where on December 28, 1221, the boy choristers were still celebrating with bonfires the heathen festival of the winter solstice (Sonnenwende) , the way leads „Am Platz“ and down the Friesenstieg to the Braunschweiger-Strasse, with its wealth of interesting houses. And at the head of the long Wollenweber-Strasse there comes a sight which one is glad to carry away as the final impression of this fairy town.

Flanked by quaint carven houses, there rises, from the old city wall beyond, the beautiful Kehrwieder Turm, or Turn-again Tower.

Once upon a time when all the world was young, the little bell in this Kehrwieder Turm rang out for the Maid of Hildesheim as she was wandering, lost, in the deep woods down beyond the wall, calling her back to her beloved city.

And to this day, as the Fountain of Trevi calls back to the sound of its murmuring waters all who have known the Eternal City, so the Kehrwieder Turm forever rings out to all who have come under the magical spell of Hildesheim— „Turn Again!“

A few steps tbward the center of things destroyed this disillusion, only to bring another. I had expected to find Hildesheim a smaller, more exquisite edition of my favorite German city — a little Brunswick de luxe with a jeweled clasp. Instead I found its counterpart, and within the next few hours was forced to reconstruct all my ideas of the place.

Brunswick is democratic, a city of plain people. Hildesheim is aristocratic, as befits the ancient see of a line of great prelate princes. Brunswick's charm is mainly Gothic; Hildesheim's, mainly Romanesque and Renaissance. There the churches are subservient to the wonderful, homogeneous old streets about them; the houses are sincere expressions of strong individuality. Here the real key-note of the place is struck by such magnificent church interiors as St. Michael's and St. Godehard's. Many of these houses are richer, more picturesque than those of Brunswick, but the rich facades are in glaring contrast to the poorer ones, and often show, instead of personal initiative, a desire to emulate the pomp, the learning, the solemn circumstance of the bishops. In Hildesheim there is a marked absence of the familiar, informal little courts, the grotesque friezes, the homely, humorous carvings and niottos that make Brunswick such an intimate place. Inscriptions are there a-plenty, but most of them are pompous or stilted, ill-natured, didactic, or melancholy, and a great many are in ostentatious Latin. It is clear that the old Hildesheimers were not so happy in their exclusiveness as were the Brunswickers in their democracy. Instead of the genial clowns and mermen, the tugs of war, the musical asses and apes, the domesticated gargoyles, behold reliefs of the Virtues and the Vices, of the Arts, Sciences, Elements, Seasons, — all with neat Latin labels that remind one of the scrolls issuing from the mouths of figures in old-fashioned woodcuts. And the few saints left over from Gothic times keep shockingly indiscriminate company, not with Low-German sinners, but with the gods of Greece and Rome. I have known no other private architecture with so strong a didactic and homiletic flavor as that which these Hildesheimers assimilated from their pious overlords.

But if the place gives one the impression of being always on her good behavior and a trifle self-con- scious, she more than makes up for it by her wealth of legend. Fairy fingers have woven gleaming strands about many of her choicest treasures, and in the length and breadth of the German land there are few legends more lovely than that of the origin of Hildesheim. This is one of the many variants:

In the year 815, Emperor Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, was hunting in the outskirts of the Hercynian forest, and, in following a white buck, he outdistanced his followers and lost both his quarry, his horse, and his way in the Innerste River. The Emperor swam to shore and wandered alone until he came to a mound sacred to the ancient Saxon goddess Hulda — a beautiful mound covered with her own flower, the wild rose. Again and again he sounded his hunting-horn, but there was no answer. Then he drew from his bosom a casket containing relics of the Holy Virgin, and, while praying before it for rescue, fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke the mound where he lay was covered with snow, although it was high summer and everything about was green. The roses on the sacred mound were blooming more brilliantly than ever. He looked for the reliquary and found it frozen fast amid the thorns of a great rose-bush. Then the Emperor knew that the heathen goddess had, „by shaking her bed,“ sent the holy snow in token that the Christian goddess should now be worshiped in her stead. „When his followers finally discovered him he had resolved to build on that mound a cathedral to the Virgin Mary. And to-day on the choir of this cathedral that very rose-bush is still in bloom.

All this is by no means a pure fiction. For it is certain that the spot was a headquarters of the old Saxon religion; that Louis transferred the Eastphalian see here from Elze in 815; and that nobody knows how many centuries old the roots of the famous rose-bush really are. Where it grows is the birthplace of Hildesheim, a name thought to mean „Hulda's Home,“ and the old cloisters that inclose it are worthy of their situation. In the autumn, when their smothering of woodbine breaks forth into scarlet and old rose and carnelian, into all pinks and oranges and purples— brought out the more by the deep browns and grays and yellows of the double arcade — it needs neither the Thousand-year Rosebush, nor the crumbling tombs, nor the charming Gothic chapel, with its devout gargoyles, that is set in the midst, to make this cloister garden one of the sweetest shrines ever dedicated to the contemplative life.

Out of this beautiful beginning grew a city that has, ever after, seemed suffused with the romaunt of the rose. The first small, fortified settlement about the cathedral, called the Domburg, was surrounded with rose-hedges which became the godmothers of such streets as Long-hedge, Short-hedge, Flood-hedge, and the trio of Rose-hedges (Rosenhagen I, II, and III). And there is a tradition that each of the cathedral clergy is warned of his own death three days beforehand by a white rose which he finds in his choir-stall.

In the eighteenth century, sad to relate, the ancient, austere splendor of the cathedral interior was transformed into a baroque splendor that shows particularly tawdry and frivolous against the few remains of Romanesque construction and the notable treasures of early art that fill the building. Though the architecture of this cathedral is not to be compared with Brunswick's, yet the place is fully as interesting. For here the famous bronze doors, the Christ Pillar, and the font far outshine the trinity of Romanesque sculptures there.

The bronze doors were finished in 1015 by St. Bernward of Hildesheim, one of the most illustrious of German bishops, celebrated as teacher, architect, sculptor, and friend of three emperors. Standing before them, one is filled with astonishment on remembering that this was the virgin appearance of art in a region hitherto artless. It is a miracle of precocity. For these reliefs, though crude, are far more direct and elemental, and touch the heart more deeply, in their naive blend of humor and pathos and religious fervor, than Ghiberti's doors on the Florentine baptistery.

During his visit to Rome in the year 1001, St. Bernward borrowed his main idea from the doors of St. Sabina; and his Christ Pillar was executed in the spirit of the Column of Trajan.

It is peculiarly fitting that these works, representing the miraculous birth of German art, should be accompanied by the thirteenth-century font that stands for the culmination of Romanesque brazen sculpture in the North.

In the nave hangs a reminder of that Bishop Hezilo who urged on his bloody band from the high altar of Goslar. It is an immense chandelier in the form of the heavenly Jerusalem, a battlemented ring-wall of exquisite filigree broken by twelve towers and twelve portals.

Before the elaborate Renaissance reredos stands a column of polished stone bearing a Madonna. The people of Hildesheim firmly believe it to be a part of the original Irmensaule that stood near the city in the Dark Ages and marked the principal shrine of the Old Saxon god Irmin. They say that Charlemagne cast it down and broke it with his own hand in his vigorous attempt to Christianize the heathen — a conception inhumanly abused by certain German professors who have an almost puritanical hatred of the glamourous and force every attractive idea to stand trial for its life. In their despite I prefer to believe that this is the authentic heathen pillar, and that the relics of the Virgin were really frozen by the sacred snow in the rose-bush outside, more than a millennium ago.

At any rate, one may see in the treasury the very reliquary that contained those relics, besides many other precious things, such as the gemmed fork of Charlemagne, a sliver of the true cross, the head of Oswald, King of Northumbria, who died in the year 642, the geometry from which the holy Bernward taught Emperor Otto III. And all at once you come upon a thing that transports you in a trice beyond the Alps into the hush of another holy treasure- house below the hill of Fiesole. It is a perfect Uttle altar by Fra Angelico.

Worn out by the incessant demands of so much beauty, I left the building to rest for an hour on the smooth lawns, beneath the venerable lindens of the Domhof. The treasury had taken me to „the warm South“; but here for the first time on my pilgrimage I caught a breath of the peaceful seclusion, the idyllic secret charm of the English cathedral close.

A citizen came to sit beside me and to relate how, in that very place, until the middle of the eighteenth century, the boys of Hildesheim had annually played at Charlemagne and the Heathen, a game in which the Irmensäule in effigy was finally stoned and overthrown.

The old gentleman pointed to the gilded cathedral cupola that sheltered the old heathen pillar. „That also has a story,“ he said. „In the year 1367 the Brunswickers surprised us in overpowering numbers. Then good Bishop Gerhardt put himself at the head of our little army and prayed to the Holy Virgin. 'It is for thee to decide now whether thou wilt live henceforth under a roof of thatch or of gold.' As our men approached the great host of Brunswick, they were dismayed but the Bishop stretched forth his left arm, crying, 'Leven Kerle, truret nich, hier hebbe ek noch dusend in miner Maven.' ('My dear fellows, be not dismayed. I have here a thousand more [men] up my sleeve.') Then they knew that the good bishop carried in his sleeve Hildesheim's greatest treasure, the reliquary of the Virgin, and, taking heart, they put the enemy to rout, slaying fifteen hundred of them and capturing rich spoils. Ever since,“ the old gentleman concluded, „our dear Lady has lived under a golden roof.“

Not far from this quiet close I found another feast of beauty.

The lawns and gardens surrounding the Church of St. Michael meant renewed thoughts of old England, and the interior brought back like a refrain the holiest memories of Italy. For though the Romanesque is more truly the national style of Germany than any other, yet this most perfect of Northern Romanesque interiors cannot help suggesting the land of its birth. The alternation of light and dark blocks in the transept arches reminds one of Siena, while the pure beauty and variety of the capitals take one back to Ravenna. These capitals pass from the simple „dice“ design of the year 1000 to the timid attempts at low relief of the middle, and the high relief of the end of the eleventh century, with grotesques and even medallions between the angel corners. These, in turn, pass into the luxuriant stone foliage of the twelfth century, peopled with little faces and figures.

It pays to prowl long in St. Michael's, for there is many a surprise in store for the appreciative, such as the eight archaic beatitudes over the columns of the southern aisle, with their hint of Assyrian influence; or the delightful angels and saints on each side of the wall separating the western choir from the northern transept; the tombs, the altarpieces, and the crypt where Bernward reposes and shows himself even here for the saint and artist that he was by the flowing Latin hexameters of his own epitaph. It is a satisfaction to know that he made his famous doors and Christ Pillar for this sanctuary, and that they have not, until recent years, been compelled to endure the baroque cathedral interior.

St. Michael's crowning glory is the painted wooden ceiling of 1180, the only one of its kind north of the Alps. It gives the genealogy of Christ from Adam down, with a feeling for composition, a restraint, and a knowledge of anatomy quite unusual in Romanesque painting. And there is a touch, too, of the Germany we know. For if you look long enough you discover that the tree back of Eve is filled with portraits of the five senses, while in Adam's tree reposes the Herrgott himself — a conception truly German in its lack of gallantry.

It is an uncanny experience to be dreaming alone in this church and to be roused by a sudden chorus of horrible laughter and heartrending shrieks from the insane in the adjoining cloisters, which are now used as an asylum. And it is even more distressing to visit the cloisters and see the poor souls hurrying about distractedly among the foliage and flowers, without the least appreciation for the lovely arcades and portals where the late Romanesque is so happily fused with the early Gothic.

The Church of the Magdalene is worth visiting for the sake of its three treasures: a jeweled cross containing splinters of the true cross, and a pair of wonderful candlesticks, all the work of Bernward and prophetic of the Renaissance goldsmiths of Nuremberg.

It is not often that one city possesses two leading examples of the same architectural style. But St. Godehard's is one of St. Michael's dearest rivals and even surpasses the sister church in the purity and homogeneity of its ornament, though it has recently been disfigured by a great deal of garish paint. It has, besides, an interesting portal and a precious little treasury.

The Church of the Cross is one of those fascinating churches that are coming more and more to light in our day— churches built originally to war not against spiritual wickedness, but against flesh and blood. For the Kreuz Kirche was originally an outwork of the Bishop's Fortress on Cathedral Hill. And the chronicler Saxo records that toward the end of the eleventh century Bishop Hezilo changed it from a home of war (domum belli) to a home of peace (domum pacis) — a transformation even more commendable than that of swords into plowshares. May this act not have been in expiation of Hezilo's share in the „Blood-bath“ at Goslar?

The town halls of Hildesheim and of Brunswick neatly contrast the spirit of the two places. The low, level Rathaus of democratic Brunswick is faced with a series of ten double arcades, all free and equal. Hildesheim's Rathaus sounds a note unmistakably aristocratic, with its commanding western gable flanked by proud clock- and window-towers.

The interior at Brunswick is plain; here it is resplendent. And it is a significant fact that the fine frescos of local history and legend, begun by Prell in 1887, were the pioneers of the recent German revival of the old al fresco technique. The building teems with legend.

On the apex of the western facade the Hildesheimer Jungfer, the Maid of Hildesheim, stands proudly under a baldachin. She is supposed to be no other than the old heathen goddess who sent the sacred snow, and who once, in the form of the Holy Virgin, appeared to a maiden lost in the woods beyond the wall and led her back to her home. She it was who used to stand on the ramparts in time of siege and catch the cannon-balls of the foe in her apron. So that, out of gratitude, the Hildesheimers graved her image on their municipal banner and seal.

On the clock-tower, below the red-frocked town piper, who pipes the halves and trumpets the hours, is the head of a Jew who opens and closes his eyes and mouth at the sound of the trumpet, as if in pain at the thought of another unprofitable hour gone by. They call it the head of a would-be traitor who was caught in the fact and shut in the Rathaus dungeon to die of starvation.

In the northern wall a measure is chiseled, with these words: „Dat is de Garen mathe.“ („This is the measure for yarn.“) You are told that the widow of a local yarn-dealer was once wakened by her late spouse, who complained bitterly that he had to suffer so much pain in his present home because, in life, he had bought with a long measure and sold with a short one. Whereupon he cast an iron ruler upon the table, crying, „Dat is de Garen mathe!“ and vanished. When the widow came to her senses the ruler had disappeared, but the measure was burned through the table, through all the floors of the house, and so deep beneath the cellar that the bottom of the hole could not be plumbed. Then the magistrate graved the length of the measure upon the wall of the Rathaus as an abiding stimulus to honesty. It is possible that the moral reaction after this incident inspired the rather optimistic inscription on the Kramergildehaus in the Andreas-Platz:

Weget recht un glike,

So werdet gi salich un ricke.

(Weigh justly and equally, which

Will make you happy and rich.)

What draws most of us, after all, to Hildesheim is not the lure of its churches and public buildings, potent as it is; but rather the lure of the quaint streets and squares, and of the houses where German private architecture touches its zenith. Though these distinguished dwellings are not jolly and intimate like Brunswick's, they are more glamourous. These narrow, „Haufendorf“ streets disengage no least hint of Brunswick's democracy, but they are the abiding-places of romance. And, touched by the shadow of these strange, rich façades, the traveler peers instinctively into every coach that clatters by for a glimpse of the fairy godmother with her magic wand, of the little kobold with the wishing-ring for the first who may befriend him, or of an authentic local sprite like Hütchen of the large hat, or Huckup the bogy-man of Hildesheim, whose statue is under the big tree in the Hoher Weg. Nor is this curiosity unjustifiable. For what has happened may happen; and Hildesheim has, in its day, supplied the stuff for many a fairy-tale. There is, for example, the true story of the Little Princess:

Once upon a time there came to Bakermaster L — in the Goschen-Strasse a beautiful maiden begging for work. The old man put on his spectacles, noted her delicate features and soft hands, and sent her about her business. „Thank heaven,“ he cried, „that we no longer need a nurse-maid! Now if you were only the sort to do heavy barn and field work we might give you a trial.“

The maiden wept bitterly, protesting that nothing worthy a servant was foreign to her nature. So the kind-hearted baker consented to try her.

She was a decided success. The cows were kept as soft and sleek as cats, and no man could keep up with her in the field. So that the old couple were charmed and loved her as their own daughter.

When the neighbors dropped in of an evening to discuss the hard times and the war over a mug and a pipe, the maiden, who sat by at the spinning-wheel, would often join in and talk of emperors and kings as though she were quite at home with such folk. Then some one would speak up:

„Maiden, you seem to know the world well. Where, then, do you come from?“

But she would only heave a deep sigh and moisten her flax with her tears.

There was one old fellow who liked to pinch her rosy cheeks when no one was looking and call her the Little Princess. And presently the whole neighborhood took up the name.

One morning the baker's farm-wagon was unloading before his portal, and the Little Princess was so busy with her pitchfork that she did not hear the cries and huzzas that suddenly burst forth around her. The whole Goschen-Strasse was so packed with folk that an apple could n't have fallen to the ground (dass kein Apfel mehr zur Erde konnte).

A company of gold-laced lackeys made way with their silver drum-majors' sticks for a great float filled with more than a hundred Moors and apes who rent the air with trumpet and drum.

Only the Little Princess labored on and took no notice.

Finally came a golden coach-and-six. A beautiful knight, clad in gold and silver, sprang out, caught the Little Princess in his arms, and exclaimed: „Ah, my heart's love, Marianne, our time of probation is over! The Kaiser has been beaten, and we may now be married!“

The lackeys sprang to lift her into the coach.

„But,“ protested the Little Princess, „only see how I look! Let me first change my dress.“

„Nay, nay!“ cried the prince, proudly. „This dress we will keep forever as a memento.“

Then the prince threw the astonished bakermaster a great purse of gold, and they vanished amid the acclamations of the populace.

Though the Goschen-Strasse is one of the plainest streets in town, one glance at it will convince any skeptic that this story is true. Such things happen inevitably in such a setting. And in wandering through the richer streets one's imagination is positively overpowered with all the surprising and lovely events that have, or ought to have, taken place there. It is like walking bodily through the pages of Grimm.

In our day it is the mode to shrug one's shoulders at the German Renaissance. And, indeed, what with the tenacity of its predecessor the Gothic, and the untimely disaster of the Thirty Years' War, the style had small chance to mature in the Fatherland.

But no one who knows such places as Hildesheim and Nuremberg, Danzig and Rothenburg— towns especially spared in the great war— can feel like scoffing at the German Renaissance. For there the style makes up in picturesqueness for its departure from the canons of Italian proportion. It is like the young poet at college who abjures conic sections to go in for literature and music. Its faults are simply the extravagances of romantic youth. For the German Renaissance is, at its best, eternally young and eternally romantic.

It must have been a dim realization that this fresh charm scarcely befitted their proud, pious aristocracy that made the Hildesheimers try to counteract its effect with solemn, pompous, pedantic carvings and inscriptions.

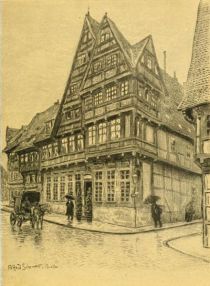

The „Old-German House,“ for instance, at the head of the Oster-Strasse is a delightful composition of three sharp gables with a great bay-window as high as the roof and four tiers of wooden friezes, inimitable at a distance. But these turn out to be representations of the elements and the heavenly bodies, and prominent among them is Death with a youth, a sage, and this motto:

Hodie mihi — cras tibi.

(To-day for me — to-morrow for thee.)

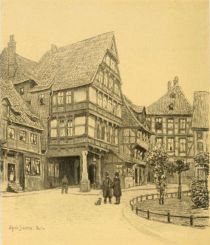

These wide, lofty bays are as characteristic of Hildesheim as small, delicate oriels are of Nuremberg. And it would be hard to decide which kind is the more picturesque. There are two fine bays in the Wedekind House in the Markt, with a seven-storied gable rising between them. The whole house is overspun with filigree like one of the elaborate reliquaries in the cathedral, with an effect indescribably vivacious. But these, floor by floor, are the subjects of the carvings:

I. Truth, Justice, Charity, Hope, Wealth, Prudence, Fortitude, Courage, Temperance, Patience, Faith.

II. Grammar, Dialectics, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Music, Woman with Pitcher and Glass, Geometry, Woman with Soap-bubble, Astrology.

III. A Tower (earth), A Ship (water), A Thunderbolt (fire). Avarice, Air, Sloth, Woman with Pitcher, Pride, Luxury, Appetite, Envy, Wrath.

Even the kind ladies with pitchers, there doubtless to moisten these dry abstractions, must have appeared with the sanction of those ecclesiastics who opened Hildesheim's first saloon under the auspices of the cathedral.

There are many pious inscriptions, such as:

Affgunst der ludc kann dich nicht schaden,

was Godt will das muss geraden.

(Man's malice cannot injure you;

What God intends that must go through.)

Here is a hint of the truculent, misanthropic note that reechoes constantly in the inscriptions of these aristocrats and would-be aristocrats.

The Wedekind House shows the more elaborate and nervous by contrast with the dignified Gothic „Temple House“ next door, with its narrow, trefoiled windows, its great spaces of repose, and the loopholed watch-turrets on each side.

And the Roland Fountain before them helps to harmonize the two houses, combining as it does the decorativeness of the one with the nobility and calm of the other.

Across the Markt is a corner which every lover of Germany holds as a hallowed spot. Here stands the Butchers' gildhouse — the Knochenhaueramtshaus — famed as the finest half-timbered building in the land. It is a splendid specimen of the early Renaissance, and, through its model in the leading museums, the world has come to love the rhythmical proportions of its baldly projecting stories, its sharp, lofty gable, its purely modeled corbels and friezes. So that its partial destruction by fire in 1884 was mourned as an international calamity. Through this fire one of the mottos on the eastern façade was given a lamentable architectural application:

Arm und reich,

Der Tod macht Alles gleich.

(For poor and rich the sequel

By Death is brought out equal.)

But the house has been splendidly restored.

It would be useless to attempt describing within these limits allpf the most fascinating among the four hundred noteworthy old houses of Hildesheim. It must suffice merely to mention a few types.

On the corner where one comes to the Hoher Weg is the Ratsapotheke, with its long-winded Latin hexameters and German doggerel and with one of Hildesheim' s few fine Renaissance portals. Farther on is the old Ratsweinschenke, with solemn biblical illustrations of the wine business such as the Noah episode and the spies importing grapes from the Promised Land.

The Hildesheimers liked to copy the architecture as well as the customs of their friends the fairies. The fa9ade of the Kaiserhaus is a thing as curiously inverted as a „goop.“ For the elaborate stone oriel and portal reproduce the wood-carver's technique so well that thej'- seem petrified, and the expanse of wall filled with medallions of Roman emperors seems as if copied from some rich ceiling of paneled oak.

These people were fond of building toy streets like the Hoken and the Juden-Strasse — streets almost as narrow as the narrowest Venetian lanes; streets whose houses, set capriciously askew, almost allow opposite neighbors to shake hands from their projecting stories.

They delighted in toy houses like the little one in the Andreas-Platz, set perpendicular to the sharply sloping street; or the Pillar House, under which the way leads into the square. This beautiful dwelling is a veritable picture-book of the Virtues, the Muses, and the gods of Rome. One unconsciously expects these wooden people to come alive all of a sudden, like the gingerbread children on the witch's house in „Hänsel und Gretel.“ It might well have really been a witch's house; for many such old persons have been done to death in Hildesheim. There is only one thing to spoil its delightful atmosphere. It is that self-conscious quotation about mens conscia recti.

The Hildesheimers were fond of composing an amusing line of roofs such as the one northeast of St. Andrew's, and of leaving one grand old Gothic house (like Trinity Hospital) to temper the vivacity of a Renaissance neighborhood like an ancient oak set in a grove of silver birches.

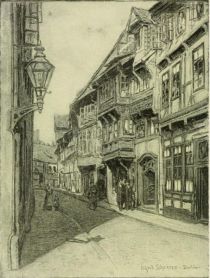

They were fond of packing alleys full of romantic, strangely formed gables, and winding them alluringly away into the unknown as they wound the Eckemecker-Strasse away from the dominating tower of St. Andrew's. This street name is onomatopoetic; for, with its suggestion of bleating flocks, it means „The Street of Sheepskin Tanners.“ It is a name fitter for laughing Brunswick than for longfaced Hildesheim. Here stands one of the most fascinating houses in town, the Roland Hospital, with its tall, characteristic bay and its five far-projecting stories adorned with scenes from the former rural life of Simon Arnholt, its builder, such as sheep- shearing, hunting, wine-making, pig-sticking, sowing, and sandbagging the police. At least, I thought them police at first, but found later that they were only Philistines being smitten with the jaw-bone of an ass. And there is an inscription with the same old note of defiance, as though whoever built a fine house in this place had to become a mark for envious tongues:

Wer bawen will an freier strassen,

muss sich vel unnütz geswetz nich iren lassen.

(He who would build upon the public walk

Must not be turned aside by idle talk.)

The Schuh-Strasse runs parallel to the Eckemecker- Strasse and, in the matter of picturesqueness, is a worthy companion. But you will find more noteworthy houses by turning down the Bohlweg — which derives its name from the planks, or Bohlen, laid down in olden times for crossing the marshy remnants of the cathedral moat. Here, at the head of the Kreuz-Strasse, is the Domschenke, or Cathedral Wine-house; and opposite is its first rival, the Golden Angel, a charming early Renaissance building called „Der Alte Schaden“ (The Old Damage), because it damaged the monopoly of the Domschenke. It bears a relief of five horses straining at three wine-butts; and behind them appears mine host solemnly reckoning up his gains.

Not many doors down the Kreuz-Strasse is the tavern called „Der Neue Schaden“ (the New Damage), the second rival. And a serious rival it was; for it introduced into Hildesheim that pale amber fluid which was destined never to check its mad career until it became the national drink. This fine transition façade actually bears humorous carvings.

„Fish-tailed persons,“ writes learned Herr Gerland, „are drinking there and experiencing all the effects of drinking, while heads, interposed, reflect the impressions which are produced upon them by these phenomena.“

No wonder the New Damage was so daring as to be humorous, for that jolly tavern was always the hotbed of radicalism. And in Luther's time it was the headquarters of the Reformation Club, which used to make it a base of supplies in their horse-play campaigns against the old-fogy Catholics. It is easy to imagine what these zealous youths must have done to the Reformation chronicler Johannes Oldecop, Dean of the Holy Cross. For, upon the façade of his house around the corner, the old gentleman poured out all his bitterness against the new faith. His fury may be seen even in the jumbled order of the words, which read like a Chinese puzzle:

Anno dm. 1549. Virtus, ecclesia. clerus demon, simonia. cessat. turbatur. errat. regnat. dominatur. verbum dni manet in eternum nil nisi divinum stabile, humana laborant, lignea cum saxis sunt peritura

(a.d. 1549. Virtue ceases, the church is in an uproar, the clergy has gone astray, the devil rules, simony reigns. God's word remains for all eternity. The divine alone stands. The human is in peril. Wood and stone will pass away.)

Past the Square of the Holy Cross, where on December 28, 1221, the boy choristers were still celebrating with bonfires the heathen festival of the winter solstice (Sonnenwende) , the way leads „Am Platz“ and down the Friesenstieg to the Braunschweiger-Strasse, with its wealth of interesting houses. And at the head of the long Wollenweber-Strasse there comes a sight which one is glad to carry away as the final impression of this fairy town.

Flanked by quaint carven houses, there rises, from the old city wall beyond, the beautiful Kehrwieder Turm, or Turn-again Tower.

Once upon a time when all the world was young, the little bell in this Kehrwieder Turm rang out for the Maid of Hildesheim as she was wandering, lost, in the deep woods down beyond the wall, calling her back to her beloved city.

And to this day, as the Fountain of Trevi calls back to the sound of its murmuring waters all who have known the Eternal City, so the Kehrwieder Turm forever rings out to all who have come under the magical spell of Hildesheim— „Turn Again!“

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

Hildesheim — Cathedral Cloisters. The Thousand-year Rose-bush. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

Hildesheim — The Nave of St. Michaels Church. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

Hildesheim — „The Old-German House“. Drawn by Alfred Scherres.

Hildesheim — The Rathaus (left). Temple House and Wedekind House in the Market-Place. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

Hildesheim — The Pillar House in the Andreas-Platz. Drawn by Alfred Scherres.

Hildesheim — The Eckemecker-Strasse. Drawn by Alfred Scherres.

alle Kapitel sehen