V. Goslar in the Harz.

Modulation is as important an element of the art of traveling as it is of I those cousin arts, painting and music. I have had occasion to speak of getting the soul down from the shrill modern key of Berlin to the deep, mellow tonality of old Danzig. But there is another sort of modulation, quite as important to the traveler and more difficult. It is a smooth transition from the simple, deliberate, careless romanza of outdoor life to the exciting, exacting, exhausting scherzo movement of some rich historic city where attention, memory, and sympathy are every moment astrain.

In recuperating from the exhausting demands of a tour among the Northern cities the lover of beauty is often tempted to lose all sense of the flow of time in wandering with Rucksack and staff among the evergreen forests of the Harz Mountains, following where the charming Oker's music leads; idling in the fabled region where sleeps Barbarossa, his red beard grown clean through the table; or held fast in the „wild romantisch“ gorge of the Bode Thal, where, from each wall of cliff, the Hexentanzplatz and the Rosstrappe look down on the river boiling far beneath.

Standing on that lofty crag whence the princess, pursued by the giant, made her mythical leap across the valley and left her horse's hoof-print in the rock, the traveler gazes over the sandy level that is North Germany and makes out on the horizon, far beyond the spires of Quedlinburg and of Halberstadt, the massive towers of Magdeburg cathedral.

With a start he realizes that there are other wonders in this region than mountains and rivers and their genii. The fever of civilization seizes him. Rashly importunate, he crashes down on the itinerant keyboard with both elbows and rushes headlong into such a bewildering treasure-house of the ages as Halberstadt or Hildesheim.

The transition is too abrupt. He is no longer used to cathedrals and Rembrandts and streets of Gothic houses with overlapping stories. If his time in Germany is really inelastic it would be far wiser to lop a day or two from Berlin or Leipsic or Frankfort, from Dresden or even from Munich, and so make his journey conform to the canons of the art of traveling.

Suppose that our tourist should, for example, actually come to his senses at Thale. Let him not make a hysterical dash at Hildesheim, but rather stop over a train at little Wernigerode to marvel at the ancient Rathaus and empty a glass in its vaulted cellar; to enjoy a slight foretaste of what the half-timbered houses of the Harz country are like; and then move on for a day in the more impressive and interesting town of Goslar, with its august history and its curious legends.

Your entry into town is reminiscent of Nuremberg; for you come at once upon a huge, round fortress tower guarding the approach. But instead of lingering here you hasten to the farther end of town to see the building that made Goslar famous— its very raison d'etre.

Goslar came into the world because it lay on the fringe of the Harz forests and at the foot of the silver-yielding Rammelsberg, both of which were owned by the ninth-century emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. They put up there a succession of hunting-lodges and small palaces until Emperor Henry III built the Kaiserhaus, which is to-day the oldest secular building in Germany. Here Henry IV began his ill-starred life. His preference for living at Goslar and the number of castles he built in the neighborhood roused the fears of the Saxon nobles, who tried to assassinate him one evening at the Kaiserhaus. And this was the opening scene of the drama that culminated at Canossa, when, barefooted, the Emperor waited three days in the snow before Pope Gregory's portal.

The last Holy Roman emperor in these spacious halls was Barbarossa. After him the noble building gradually fell into ruin until the coming of the new empire, when it was restored in a rather hard Prussian style, and received into its halls the second great German leader, William I. Now, in bronze, the pair sit their war-horses on either side of the main flight of steps — Barbarossa and Barbablanca, as the people call them.

The main hall is decorated with frescos of the Sleeping Beauty and the Barbarossa legends, and scenes from local and imperial history. Its principal attraction is the old Kaiserstuhl, seat of a long line of emperors.

In the chapel of St. Ulrich the heart of Henry III lies buried. It lay formerly in the famous cathedral which Henry built near his palace and which was torn down in 1819. This piece of vanished glory possessed an extraordinary collection of treasures and relics. It made nothing of the bones of such saints as Nicholas, Laurence, Cyril, and Dionysius; for it boasted important remains of the Apostles themselves. There was half of the Apostle Philip, an arm of Bartholomew and one of James, a hand, arm, and the head of Matthew, and a large part of the bodies of Peter and Paul. There were also, among other wonders, an original portrait of St. Matthew and part of a nail from the true cross.

Many of these valuables were stolen in Goslar's sack by Gunzelin in 1206, and when the Swedes occupied the town four years during the Thirty Years' War. Others were sold to keep up the cathedral during the hard times brought on by the Reformation. So that the only remnant of the building and its treasures to-day is a part of one transept near the Kaiserhaus, with some interesting statues, some of the oldest stained glass in existence, and an early Romanesque reliquarium borne by still earlier brazen figures of the Four Rivers of Paradise, old as the city itself. From this one piteous fragment with its sculptured portal one can reconstruct the whole— ex pede Herculem — and realize the effect of a religious pageant on one of Goslar's chief holy days, such as the feast of St. Matthew, when the bells in the twin towers went mad, when Henry III in his imperial robes swept down the broad steps of the Kaiserhaus, heading a brilliant train of prelates, princes, knights, and many a band of pilgrims who had come from every part of the empire to bow at this famous shrine. And after the last Amen had died away among the lofty vaulting of the cathedral, St. Matthew in his silver sarcophagus was carried with due rites about the city walls.

These occasions, however, were not always peaceful. For Widerad, Abbot of Fulda, once quarreled with Hezilo, Bishop of Hildesheim, over a matter of precedence. Both brought armed followers to the cathedral, and a bloody fight broke out in the choir, the bishop standing on the steps of the high altar and urging on his men with all his resources of dis- pensation and absolution. Legend has mingled with this story of the „Blood-bath“ and relates that the encounter had been arranged by the Evil One himself, who now rolled about behind the bishop and held his belly in convulsions of laughter (lialte sich den Bauch vor Lachen). Finally he flew away through the roof, calling out, „I 've made this day a bloody one!“ and left a broad crack which could not be walled up until some one hit on the expedient of stuffing a Bible into the breach.

These buildings, then, the Kaiserhaus and the Domkapelle, are the only local Sehenswürdigkeiten ersten Ranges — the only „see-worthinesses of the first class.“ That is why Goslar makes such a smooth modulation to Hildesheim. Here you have a mere taste of the labor of conscientious sight-seeing; then for the balance of your stay you feel at liberty to send your conscience to the hotel, while you yourself drift about happy, careless, and Baedekerless, seeking what your eyes may devour. In other words, you put down the big history book for an hour's ramble through the illustrated magazine.

Perhaps you come upon a mighty round tower embowered in trees beyond the waters of the Kahnteich. It is the old Zwinger, largest of Goslar's original one hundred and eighty-two towers of defense, and .capable of holding a thousand armored warriors. Or you happen upon an anomalous building, a cross between church and dwelling, with columned windows, a generous spread of roof filled with little dormers, and, above, a projection undecided whether to be a steeple or a chimney. You venture through the Gothic portal and see long sweeps of raftered ceiling, and gloomy wooden balconies, and no end of tiny rooms where old women sit about knitting humbly and making, with their surroundings, the most delightful Dutch genre pictures of the sixteeenth century. Then one of the old ladies comes out', accepts a copper with deprecation, and quavers out that this is, please, the almshouse of the Great Holy Cross.

Or you meander along the diminutive Gose River, that gave the city its name (lar is old Franconian for „home“). You find a delightful mill, and fall to sketching — or wish that you could fall. And you break into the adjoining Glockengiesser-Strasse and think of the bell-caster of Goslar who cast the famous cathedral bells there and the spooky fountain in the Markt, and whose ancestor perhaps did the Four Rivers of Paradise in the Domkapelle.

You appreciate the half-timbered dwellings so much that your appetite is whetted for better ones. If you are persistent you find them at the head of the Markt-Strasse. Crescit indulgens! The taste grows upon you. Presently, unless you are very reserved or blase, you give a cry of pleasure. You have discovered the Brusttuch, a crooked late-Gothic gildliouse named after an indispensable part of the local peasant's costume. It has an amazingly sharp, high ridge. Its lowest story is of picturesque rough stone; its second is half-timbered and filled with such homely, humorous carvings as riot along the streets of Brunswick (Braunschweig). Among them are reliefs of convivial monkeys and of witches riding their broomsticks to the Brocken. With its wide oriel and flowing lines it is a charming example of the old-German patrician house, and, with its two distinguished neighbors, the Bakers' gildhouse and the Kaiserworth, forms a group more reminiscent of the houses of Nuremberg (Nürnberg) than of more northern architecture.

The simple Rathaus harmonizes well with this trio. It is especially interesting for its series of frescos, thought to be from the hand of the Nuremberg painter Wohlgemuth (although a few learned Germans deny this with frenzied gesticulations.) Another notable possession of the Rathaus is an old iron cage called „The Biting Cat,“ now unhappily fallen into innocuous desuetude. It was made to accommodate a pair of shrews.

It is well known of the fountain outside that if, at midnight, you knock three times on its lowest basin the devil will appear at once and fly away with you to his home in the neighboring Rammelsberg.

Small wonder that he is such a powerful personage here, for Goslar's churches are singularly unattractive. Perhaps they were too much overshadowed by the vanished cathedral. But the Church of the New Work contains an interesting old fresco, and its eastern apse boasts a gem of a colonnade.

Beyond the walls is a remarkable grotto chapel called Clus, hewn by hand in a mighty boulder. Legend says that the gigantic St. Christopher used to haunt the region between Goslar and Harzburg. One day he felt a pebble in his shoe — and emptied out this very boulder. Many years afterward it was made into a chapel by Agnes, the wife of Henry III, as penance for a sad mistake. For she once had her oldest servant executed for the theft of some jewelry; and when this was found years afterward in a raven's nest, she thought to save her soul by founding the Clus Chapel and the Abbey of St. Peter, whose ruins may still be seen hard by.

From here one reenters the city by the Broad Gate, the most elaborate fragment of the original fortifications. Its four massive towers made an entrance worthy to welcome any emperor; and one imagines the splendor of the Holy Roman Empire pouring in in brilliant cavalcade between those huge bastions and defying all the world to follow.

In recuperating from the exhausting demands of a tour among the Northern cities the lover of beauty is often tempted to lose all sense of the flow of time in wandering with Rucksack and staff among the evergreen forests of the Harz Mountains, following where the charming Oker's music leads; idling in the fabled region where sleeps Barbarossa, his red beard grown clean through the table; or held fast in the „wild romantisch“ gorge of the Bode Thal, where, from each wall of cliff, the Hexentanzplatz and the Rosstrappe look down on the river boiling far beneath.

Standing on that lofty crag whence the princess, pursued by the giant, made her mythical leap across the valley and left her horse's hoof-print in the rock, the traveler gazes over the sandy level that is North Germany and makes out on the horizon, far beyond the spires of Quedlinburg and of Halberstadt, the massive towers of Magdeburg cathedral.

With a start he realizes that there are other wonders in this region than mountains and rivers and their genii. The fever of civilization seizes him. Rashly importunate, he crashes down on the itinerant keyboard with both elbows and rushes headlong into such a bewildering treasure-house of the ages as Halberstadt or Hildesheim.

The transition is too abrupt. He is no longer used to cathedrals and Rembrandts and streets of Gothic houses with overlapping stories. If his time in Germany is really inelastic it would be far wiser to lop a day or two from Berlin or Leipsic or Frankfort, from Dresden or even from Munich, and so make his journey conform to the canons of the art of traveling.

Suppose that our tourist should, for example, actually come to his senses at Thale. Let him not make a hysterical dash at Hildesheim, but rather stop over a train at little Wernigerode to marvel at the ancient Rathaus and empty a glass in its vaulted cellar; to enjoy a slight foretaste of what the half-timbered houses of the Harz country are like; and then move on for a day in the more impressive and interesting town of Goslar, with its august history and its curious legends.

Your entry into town is reminiscent of Nuremberg; for you come at once upon a huge, round fortress tower guarding the approach. But instead of lingering here you hasten to the farther end of town to see the building that made Goslar famous— its very raison d'etre.

Goslar came into the world because it lay on the fringe of the Harz forests and at the foot of the silver-yielding Rammelsberg, both of which were owned by the ninth-century emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. They put up there a succession of hunting-lodges and small palaces until Emperor Henry III built the Kaiserhaus, which is to-day the oldest secular building in Germany. Here Henry IV began his ill-starred life. His preference for living at Goslar and the number of castles he built in the neighborhood roused the fears of the Saxon nobles, who tried to assassinate him one evening at the Kaiserhaus. And this was the opening scene of the drama that culminated at Canossa, when, barefooted, the Emperor waited three days in the snow before Pope Gregory's portal.

The last Holy Roman emperor in these spacious halls was Barbarossa. After him the noble building gradually fell into ruin until the coming of the new empire, when it was restored in a rather hard Prussian style, and received into its halls the second great German leader, William I. Now, in bronze, the pair sit their war-horses on either side of the main flight of steps — Barbarossa and Barbablanca, as the people call them.

The main hall is decorated with frescos of the Sleeping Beauty and the Barbarossa legends, and scenes from local and imperial history. Its principal attraction is the old Kaiserstuhl, seat of a long line of emperors.

In the chapel of St. Ulrich the heart of Henry III lies buried. It lay formerly in the famous cathedral which Henry built near his palace and which was torn down in 1819. This piece of vanished glory possessed an extraordinary collection of treasures and relics. It made nothing of the bones of such saints as Nicholas, Laurence, Cyril, and Dionysius; for it boasted important remains of the Apostles themselves. There was half of the Apostle Philip, an arm of Bartholomew and one of James, a hand, arm, and the head of Matthew, and a large part of the bodies of Peter and Paul. There were also, among other wonders, an original portrait of St. Matthew and part of a nail from the true cross.

Many of these valuables were stolen in Goslar's sack by Gunzelin in 1206, and when the Swedes occupied the town four years during the Thirty Years' War. Others were sold to keep up the cathedral during the hard times brought on by the Reformation. So that the only remnant of the building and its treasures to-day is a part of one transept near the Kaiserhaus, with some interesting statues, some of the oldest stained glass in existence, and an early Romanesque reliquarium borne by still earlier brazen figures of the Four Rivers of Paradise, old as the city itself. From this one piteous fragment with its sculptured portal one can reconstruct the whole— ex pede Herculem — and realize the effect of a religious pageant on one of Goslar's chief holy days, such as the feast of St. Matthew, when the bells in the twin towers went mad, when Henry III in his imperial robes swept down the broad steps of the Kaiserhaus, heading a brilliant train of prelates, princes, knights, and many a band of pilgrims who had come from every part of the empire to bow at this famous shrine. And after the last Amen had died away among the lofty vaulting of the cathedral, St. Matthew in his silver sarcophagus was carried with due rites about the city walls.

These occasions, however, were not always peaceful. For Widerad, Abbot of Fulda, once quarreled with Hezilo, Bishop of Hildesheim, over a matter of precedence. Both brought armed followers to the cathedral, and a bloody fight broke out in the choir, the bishop standing on the steps of the high altar and urging on his men with all his resources of dis- pensation and absolution. Legend has mingled with this story of the „Blood-bath“ and relates that the encounter had been arranged by the Evil One himself, who now rolled about behind the bishop and held his belly in convulsions of laughter (lialte sich den Bauch vor Lachen). Finally he flew away through the roof, calling out, „I 've made this day a bloody one!“ and left a broad crack which could not be walled up until some one hit on the expedient of stuffing a Bible into the breach.

These buildings, then, the Kaiserhaus and the Domkapelle, are the only local Sehenswürdigkeiten ersten Ranges — the only „see-worthinesses of the first class.“ That is why Goslar makes such a smooth modulation to Hildesheim. Here you have a mere taste of the labor of conscientious sight-seeing; then for the balance of your stay you feel at liberty to send your conscience to the hotel, while you yourself drift about happy, careless, and Baedekerless, seeking what your eyes may devour. In other words, you put down the big history book for an hour's ramble through the illustrated magazine.

Perhaps you come upon a mighty round tower embowered in trees beyond the waters of the Kahnteich. It is the old Zwinger, largest of Goslar's original one hundred and eighty-two towers of defense, and .capable of holding a thousand armored warriors. Or you happen upon an anomalous building, a cross between church and dwelling, with columned windows, a generous spread of roof filled with little dormers, and, above, a projection undecided whether to be a steeple or a chimney. You venture through the Gothic portal and see long sweeps of raftered ceiling, and gloomy wooden balconies, and no end of tiny rooms where old women sit about knitting humbly and making, with their surroundings, the most delightful Dutch genre pictures of the sixteeenth century. Then one of the old ladies comes out', accepts a copper with deprecation, and quavers out that this is, please, the almshouse of the Great Holy Cross.

Or you meander along the diminutive Gose River, that gave the city its name (lar is old Franconian for „home“). You find a delightful mill, and fall to sketching — or wish that you could fall. And you break into the adjoining Glockengiesser-Strasse and think of the bell-caster of Goslar who cast the famous cathedral bells there and the spooky fountain in the Markt, and whose ancestor perhaps did the Four Rivers of Paradise in the Domkapelle.

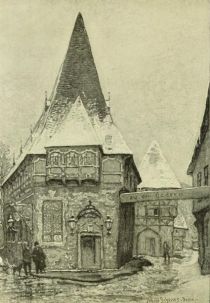

You appreciate the half-timbered dwellings so much that your appetite is whetted for better ones. If you are persistent you find them at the head of the Markt-Strasse. Crescit indulgens! The taste grows upon you. Presently, unless you are very reserved or blase, you give a cry of pleasure. You have discovered the Brusttuch, a crooked late-Gothic gildliouse named after an indispensable part of the local peasant's costume. It has an amazingly sharp, high ridge. Its lowest story is of picturesque rough stone; its second is half-timbered and filled with such homely, humorous carvings as riot along the streets of Brunswick (Braunschweig). Among them are reliefs of convivial monkeys and of witches riding their broomsticks to the Brocken. With its wide oriel and flowing lines it is a charming example of the old-German patrician house, and, with its two distinguished neighbors, the Bakers' gildhouse and the Kaiserworth, forms a group more reminiscent of the houses of Nuremberg (Nürnberg) than of more northern architecture.

The simple Rathaus harmonizes well with this trio. It is especially interesting for its series of frescos, thought to be from the hand of the Nuremberg painter Wohlgemuth (although a few learned Germans deny this with frenzied gesticulations.) Another notable possession of the Rathaus is an old iron cage called „The Biting Cat,“ now unhappily fallen into innocuous desuetude. It was made to accommodate a pair of shrews.

It is well known of the fountain outside that if, at midnight, you knock three times on its lowest basin the devil will appear at once and fly away with you to his home in the neighboring Rammelsberg.

Small wonder that he is such a powerful personage here, for Goslar's churches are singularly unattractive. Perhaps they were too much overshadowed by the vanished cathedral. But the Church of the New Work contains an interesting old fresco, and its eastern apse boasts a gem of a colonnade.

Beyond the walls is a remarkable grotto chapel called Clus, hewn by hand in a mighty boulder. Legend says that the gigantic St. Christopher used to haunt the region between Goslar and Harzburg. One day he felt a pebble in his shoe — and emptied out this very boulder. Many years afterward it was made into a chapel by Agnes, the wife of Henry III, as penance for a sad mistake. For she once had her oldest servant executed for the theft of some jewelry; and when this was found years afterward in a raven's nest, she thought to save her soul by founding the Clus Chapel and the Abbey of St. Peter, whose ruins may still be seen hard by.

From here one reenters the city by the Broad Gate, the most elaborate fragment of the original fortifications. Its four massive towers made an entrance worthy to welcome any emperor; and one imagines the splendor of the Holy Roman Empire pouring in in brilliant cavalcade between those huge bastions and defying all the world to follow.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

Goslar — The Kaiserhaus. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

Goslar — The Brusttuch. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

alle Kapitel sehen