IX. Dresden — the Florence of the Elbe.

In Dresden I began to realize that the charm of Leipsic lay in the quaint atmosphere of its old buildings, among which even trade had grown romantic, in the airiness of the many squares, in a village-like flavor of homely intimacy caught amid the modern prose of a commercial city. Meissen had been something beyond experience, a dream of strange beauty. But in Dresden I found a beauty very real and tangible, directly arousing, without complicated equipments of antiquity, the instant response of the pleasure-loving human heart, like a voluptuous melody on the cello.

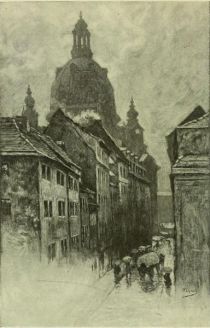

My eighteenth-century lodgings in Jews' Court gave upon the New Market, where petty trades-people from every part of central Germany were preparing for one of Dresden's characteristic Jahrmärkte, or fairs, which take place three times in the year. Every one was building himself a rude wooden booth, as for some Christian Feast of Tabernacles, while the porcelain merchants about the Church of Our Lady were unpacking acres of coarse pottery and Meissen figurines.

A lane of Dresden's fast-vanishing old houses led toward the river, and I turned on the steps of the Brühl Terrace to see how exquisitely the roofs curved upward toward where the somber mass of the Church of Our Lady, a church modeled after the Roman St. Peter's, dominated the city, the porcelain market surging white as foam about its crag-like base.

From the half -night of that lane I emerged upon a memorable scene. Far and wide, beneath, the Elbe poured between its bridges. Some boats had just landed thousands of young children, who, returning radiant from their holiday in Saxon Switzerland, swarmed in a riot of color about the candy women on the waterside below, each with a yellow ticket strung about his or her neck.

A segment of delicate pink sun drifted low beside the opera-house, sending through the hoary arches of the Augustus Bridge a fainter film of rose to rest on the river surface. Haze-colored smoke floated from steamers made fast to the shore, bedimming the Museum's flat dome, the tower of the Court Church, and the piquant spire of the castle, toning its vivid patina down to the faint fawn color of the eastward waters, and mercifully veiling the Landesrat and the opera-house, the bronze tigers of which frisked before a mass of masonry impressive in the dusk. With the waning of day, the ripples before the old bridge turned imperceptibly to liquid bronze, as light as the western heavens, lighter for the dark masses of stone behind; while to the eastward, sky and water, both a deepening fawn, brought out the gay colors of the river traffic and the rainbow of costumes along the shore.

Following an old custom, I dined at the Belvedere, where an orchestra that might be the pride of any city was playing Wagner to an audience whose very forks were dumb during the music. The acoustics were perfect; the hall was a gem in simple white and gold, and I shall not forget the pleasure of looking over those happy, cultivated faces to where, through the colonnade, the evening haze was deepening to an intense blue upon the river and the distant heights of Loschwitz.

The moon was up over the Academy of Art as I left, and the benches under the trees of the terrace outside were filled with people raptly enjoying, with the faint music, the splashes of watery light reflected from the lamps of the other shore, the murmur of the running river, and the soft silhouette of Dresden's noble bridges and towers.

Watchmen were prowling about the porcelain acres by the Church of Our Lady, and it seemed as if heaven had rained upon that favored spot a double portion of straw and sacking. The very booths of the market-place, drenched in moonlight, were touched with mystery and a kind of grotesque beauty.

Dresden is essentially a city of pleasure — of fair, wide prospects, of hearty river life, of zest in nature and art. Even the public buildings cluster about the Elbe, much as the huts of the first settlers clustered.

A circle of Wendish herdsmen's huts on the right bank, a line of fisher-shanties on the left — these were the unlikely beginnings of Dresden in the sixth century. But the settlement lay at the only point in the river valley where a ford was practicable, tempting the Germans to settle on the left bank between the Wends and the swamps, or Seen, unlovely places that have long since disappeared, leaving behind only the names See-Strasse, Am See, and Seevorstadt. Indeed, the very name of Dresden is derived from the Slavic dresjan, which means „dwellers in the swamp-forest.“

We know that the Church of Our Lady was built in the eleventh century, that until the twelfth the right and left banks of the stream were called respectively „heathen“ and „Christian,“ that Dresden was first mentioned as a city in 1216, and that the original bridge was built in 1222. The market-place in the New Town across the river still bears traces of its original Wendish form, the Rundling, or circle of huts facing an inner space with only one exit, a primitive device for guarding the cattle of the community at night.

It was prophetic of Dresden's artistic destiny that the first Margrave of Meissen to reside here (1277— 88) should have been Heinrich der Erlauchte, who was mentioned as a fellow-Minnesinger by Tannhäuser and by Walther von der Vogelweide. Heinrich married an Austrian princess, who brought to Dresden a piece of the true cross. For this a chapel was added to the Church of St. Nicholas, where it was exhibited, together with another cross that came swimming miraculously down the Elbe; and these drew such a throng of liberal pilgrims that St. Nicholas's was rebuilt as the Church of the Cross and the old wooden bridge turned into one of stone in 1319. It is curious to know that this church and the Augustus Bridge are still under one financial management.

During four troubled centuries unwarlike Dresden suffered much, and did not become important until the reign of Frederick Augustus the Strong (1694-1733)— „August the Physically Strong,“ as Carlyle loved to call him.

A gilt, rococo king, clad discrepantly in a wig and toga, he strides a gilt horse in the New Town market-place, a weak variant of Berlin's monument to the Great Elector, facing, with a faint grin, his kingdom of Poland, for which he turned Roman Catholic. Resembling Louis XIV in feature, he strove to resemble him as well in trying to revive the golden period of Roman culture and to combine, in the Zwinger, all the elegant and useful features of Roman baths and palaces.

The Zwinger was intended to unite immense banquet- and dancing-halls with baths, grottoes, colonnades, pleasure-walks, rows of trees and pillars, lawns, gardens, waterfalls, and playgrounds — a fit place to display the pomp and circumstance of royal domestic life in the ostentatious spirit of the eighteenth century. It was planned to carry the Zwinger down to the river and finish it with an unexampled palace; but Poppelmann, the architect, was able merely to build the forecourt before the royal whim veered.

This fragment, however, with its seven pavilions and connecting galleries, is unique among buildings — „the most vivacious and fanciful stone-creation of Germany,“ as Wildburg declares. „The swift evolution of late baroque,“ he continues, „into the most joyous and airy rococo, the wondrous fusing of an almost Indian imagination with German solidity and Gallic coquetry, make a gloriously artistic whole.“

The first impression made by the Zwinger on a student of history is that „August the Physically Strong“ must have had in mind the housing of his famous three hundred and fiftyfour children, and he cannot help wondering whether the chubby stone infants that cluster on each pavilion can be family portraits. The various deities scattered among these riotous princes seem frankly amused at their situation. Here is a sincerer sportiveness, a less manufactured gaiety, than I remember in any other rococo. This joyful and frivolous ornamentation was destined to become the classical example of its school, and until to-day to mold the style of the Meissen porcelain, invented in Dresden by Bottger in 1709.

The Museum, built by Gottfried Semper in the style of the Italian Renaissance, connects the ends of the Zwinger. It contains the finest gallery of paintings in Germany, a collection ranking with those of the Louvre, the Pitti, and the Uffizi. It was made in great part by August the Strong and his son August II, who had shrewd agents in the Netherlands, France, and Italy. Even the Pope and the King of Sicily did their utmost to rob Italy of its treasures for them.

Their most fortunate find was the Sistine Madonna, bought in 1753 from the monks of Piacenza for twenty thousand ducats and a plausible copy. To smuggle the picture safely across the frontier, the conspirators painted it over with a wretched landscape. When the treasure arrived, the eager king had it hung in the throne-room; and seeing that the best light fell on the dais, he shoved the throne aside with his own hands, exclaiming, „Room for the great Raphael!“

Nothing could more vividly bring out the contrast between esthetic Dresden and militant Berlin. And this contrast was emphasized three years later when Frederick the Great seized Dresden, ransacked the royal archives, and sent poor August II in a panic to the Königstein, leaving his queen behind to face the Prussians.

This war ended the gallery's rapid growth, but it had already become the most noteworthy collection north of the Alps. As early as 1756, Winckelmann, whose genius had been awakened by this gallery, called Dresden „the German Athens,“ a name that never gained the popularity of Herder's epithet, „the Florence of the Elbe.“

On entering the gallery, one's first thought is for the great Raphael. There is a hypnotic expression in the Madonna's wide eyes, which the infinite promises of that childHood have struck into trance, mirroring all the possibilities of motherhood. This intensity of vision is only accentuated by the formalism of Santa Barbara and Pope Sixtus. With Raphael's ordinary work in my mind, I was heartily surprised, years ago, by a first view of the Sistine Madonna. It was much as if, in a vision, I had heard one of a row of simpering Perugino saints burst forth into a Brahms song.

It is a commentary on the contrast between the characters of northern and middle Germany that the Dresden Gallery is poor in the early paintings of historical interest, and rich in the golden periods — an exact antithesis to Berlin.

Here Correggio, with his tenderness and his deep backgrounds, is even more fully represented than at Parma. Here Paolo Veronese may be known best — the gay Paolo in all his superficial glory, with his joy in luscious brocades set off against the gleaming of Palladian architecture.

The canvases of Giorgione are always suffused with poetry and a dreamy music, but here the hour is immortalized when Aphrodite slept while Giorgione painted. Myriad-minded Titian is almost at his height in „The Tribute Money“ and „The Marriage of St. Catherine.“ Before the exquisite, miniature altarpiece of Jan van Eyck one forgets its size, as one forgets the blindness of some great musician when he is playing his best. And here hangs one of the chief canvases of Van der Meer, that rare realist who has but lately come into his own.

Rubens is most characteristic in the mad „Boar Hunt“ and the swirling and plunging of the „Quos Ego.“

There is a humor unusual with Rembrandt in „Samson's Riddle“; and three of the master's most subtle character studies are „The Gold-weigher,“ the portrait of an old man, and that of his wife Saskia. His school is even better represented here than in Amsterdam or The Hague.

It is natural that the German painters should be weaker in Dresden than the Italian and Flemish and Dutch; for the artistic charity of the founder of the Zwinger and the Court Church did not begin at home. Nevertheless, there are a few native master-pieces. The well-known JNIeyer JNIadonna of Hol- bein was held for centuries as the original until chance discovered the present Darmstadt picture in the junk-wagon of a Parisian peddler. His portrait of the Sieur de Morette was long thought to be a Leonardo, and that of Sir Thomas Godsalve with his son is one of the most notable portraits of his English period.

Though the modern gallery is small, it is extremely select, as befits the vicinity. It contains such well-known paintings as Menzel's riotous „Market- place in Verona,“ Hofmann's „Christ in the Temple,“ and the appealing „Holy Night“ by von Uhde.

An old traveler once declared that he preferred to investigate mountains from the foot, inns from the inside, and palaces from the outside. The wanderer in Germany soon learns this method, particularly with palaces; but a visit to the Dresden castle is a mildly amusing exception to the usual rule.

Its exterior is not forbidding, like the ordinary German palace, being enlivened with red tiles, yellow plaster, and a graceful green steeple; with Renaissance gables and, in the court, with round stair-towers which recall the fact that Arnold of Westphalia rebuilt it at the time when he was creating the Albrechtsburg at Meissen.

The bedchamber of August the Strong is large, and his throne-room, adjoining, is hung with pictures of Leda and Aphrodite. The rooms are not so overladen with ornament as to be unfriendly, and one can imagine people actually taking their pleasure in the festal hall. Pictures are there, to be sure, of the inevitable Kaisers, but they look almost docile, and are neutralized by such homely frescos as „Ring Around a Rosy“ and „Washing the Baby,“ an operation not unknown to those palace walls.

The Green Vault is a place that contains earth's greatest display of knickknacks, royal playthings, and jewels. There are exhibited an ivory frigate in full sail, Siamese Twins in ivory, and one hundred and forty-two fallen angels carved out of a single tusk. In a place of honor is a dish with an elaborate representation of the „Scarlet Woman.“ There are goblets made of ostrich eggs, a silver beaker from Nuremberg in the form of a young lady, and the Bible of Gustavus Adolphus. One may see vessels and trinkets made of every stone mentioned in the Book of Revelation. A „perpetual-motion“ clock represents the Tower of Babel, whereon perch eight town pipers blowing four pipes, three trombones, and a waldhorn. Then there are wonderful Limoges enamels, the masterpieces of the old German goldsmiths, and, as a climax, the Saxon crown jewels.

After so much touristry it was natural to loll on the waterside in the quaint „Italian Village,“ a row of houses once inhabited by the Italian workmen who built the Court Church, now a restaurant and rendezvous for all genial Dresdeners. There it was pleasant to rest over a stein, and watch the river seething by between the magnificent piers of the Augustus Bridge; to enjoy through half-shut eyes the ox-eyed roofs of the New Town behind their well-wooded gardens, and the concave towers of the Japanese House, which shelters the royal library. Pleasant also to watch the divers opposite (for half of Dresden lives in the water during the hot months) , and the party-colored stream of life above, pouring back and forth over the swift stream.

Alas! they had already begun to tear down the venerable Augustus Bridge, the symbol of Dresden and its finest monument! The small, picturesque arches, dangerous to the growing river traffic, were doomed to yield to wider ones, which, as the authorities promise, are to be quite as picturesque. But the artists wonder how many centuries it will take to win back the patina of those piers.

After the sharpness of Berlin and the flatness of Leipsic, Dresden's humor is refreshing. It strikes a nice balance between satirical Berlin and softhearted, gemütlich Munich.

There is nothing brutally downright about it: it proceeds by indirection. If the Dresdener wishes to condemn the suburb of Striessen, for instance, he declares that the very sparrows take in their legs when flying over it. The pleasantry of the lower classes is of the mildest.

„In which street is the goose cooked only on one side?“

„Don't know.“

„In the little Plaunscher-Gasse, for on the other side there are no houses.“

In the plain old Rathaus there used to be a motto which is still characteristic of this town of friendliness: „One man's speech,“ runs the motto, „is a good half-speech. Hear the other man's speech, too.“ The Dresdener does not interrupt. He is not puffed up, nor does he imagine a vain thing. He is almost as polite as the Parisian, with much of the Parisian polish and savoir-faire. He is never brusque. A Berliner would call an idler „lazy,“ a Münchener would call him „ideahstic,“ but a real Dresdener would intimate that he is „not quite industrious.“ Instead of „You 're a boor,“ he says, „The honored sir appears hardly to realize that he is not conducting himself properly.“ The inquiring stranger will find him an entertaining companion who will gladly see him to the suburbs and even arrange for him, with many apologies, any neglected item of dress.

The Dresdener is orderly, modest, and quiet even in his pleasures. The very policeman is not so impressed with his position as the ordinary Prussian lackey. The Dresdener is so gentle that his very cats look altruistic, and his sparrows will hop across your feet in any beer-garden. He is so amiable that I have often been tempted to withhold a tip, to see if I could draw as much as a sigh from that paragon of Christian virtues, the waiter.

But, despite these qualities, he does not lack critical sense, defining, for instance, the Secession school of painting as „art which, if you would be cultivated, you must like at all events — whether you like it or not.“

Because Dresden has the advantages of a large city with but few of its drawbacks, it is so popular with Anglo-Saxons as to have an English and an American quarter. It is rich in painting, sculpture, music, and architecture; has fine theaters and interesting personalities; is charmingly situated and within a short ride of Saxon Switzerland, the most attractive miniature mountain range in Germany: and yet the individual still counts among its half-million people — counts even to the verge of town gossip. Despite the size of the city, neighborliness and sociability flourish like the roses of the Zwinger; and any novelty like a horse-race or an Englishman in knickerbockers lays hold of the united civic imagination.

Dresden combines the advantages of the metropolis with the humanity of the village, and one can easily forgive it for outdoing Leipsic in credulity, servility, and greed for titles, and for falling behind its neighbor in business methods.

The best place to meet the Dresdener is on the Brühl Terrace, „the balcony of Europe,“ as it was once christened by an enthusiast. Its daisy-covered walls were a part of the fortifications before Brühl, the all-powerful minister of August II, in 1736, made them over into his private gardens.

It was thrown open to the public in 1814. From the waterside, passages may still be seen leading to the ancient dungeons, now used for the imprisonment of beer. On the corner, under the Belvedere, is a crude relief of the Elector Moritz being forced by a skeleton — a „bone-man,“ as the Germans say — to hand over the electoral sword to his brother August.

This very sword is now in the Johanneum, an old building in which the historical museum and the royal collection of porcelain lodge informally above the royal stables. The portal of the courtyard is the most representative piece of Renaissance sculpture in Dresden, a fusion of German and Italian motifs setting off a relief of the Resurrection.

In the center of the court is the tank where the royal horses were washed, and an inclined horse-path leads to the second story along an ivy-matted wall above which appear the picturesque gables and spire of the castle and the tower of the Court Church.

The historical museum is mainly devoted to the history of war. No other collection has given me such a vision of the glamour and romance of chivalry or the beauty of medieval weapons and armor. Here plumed knights joust as our childhood saw them in „Ivanhoe.“ Here one feels the poetry of battle as vividly as, in the arsenal at Berlin, one feels its scientific, realistic side. This is the Scott, that the Tolstoi, of war.

The royal porcelain collection is the largest and richest of its kind in Europe. Through the austerities of the early Chinese work one gradually approaches the melting harmonies of Japanese color, then drops back centuries to the first red German ware of Bottger, and on through the early whites of Meissen, and its colored imitations of the Asiatic, to the rococo of the Zwinger and the recent Meissen ware which imitates the royal Copenhagen. Faience and Italian majolica round a collection of which the most significant part is the group of giant vases in cobalt blue given to August the Strong in 1717 by old Frederick William of Prussia in exchange for a regiment of tall dragoons.

The Albertinum cannot compare in its ancient sculpture with the Glyptothek of Munich or even with Berlin's Old Museum; but the modern sculpture gallery is important and contains a collection of medallions even more exquisitely chosen than the larger collection in Hamburg.

I shall not forget my parting from Dresden. One of the gay steamers that ply up-stream dropped me to climb the heights of. Loschwitz for a last glimpse of the German Florence from this northern Fiesole. There it lay, checkered with patches of sunlight and looking almost mysterious through a delicate mist— that duomo, the Church of Our Lady, herding its flock of comely towers, a solid Protestant antithesis to the baroque brilliance of the Catholic Court Church.

There lay the city of pleasure in all its beauty, interlaced with silvery streaks of pond and river. And toward it, sweeping parallel to the mighty arc of the Elbe, ran a broader river of smooth green meadow-land fronting the villas of the opposite shore.

Backward the peaks of Saxon Switzerland were beckoning, but it was with an unaccustomed regret that I turned my face from art to nature.

My eighteenth-century lodgings in Jews' Court gave upon the New Market, where petty trades-people from every part of central Germany were preparing for one of Dresden's characteristic Jahrmärkte, or fairs, which take place three times in the year. Every one was building himself a rude wooden booth, as for some Christian Feast of Tabernacles, while the porcelain merchants about the Church of Our Lady were unpacking acres of coarse pottery and Meissen figurines.

A lane of Dresden's fast-vanishing old houses led toward the river, and I turned on the steps of the Brühl Terrace to see how exquisitely the roofs curved upward toward where the somber mass of the Church of Our Lady, a church modeled after the Roman St. Peter's, dominated the city, the porcelain market surging white as foam about its crag-like base.

From the half -night of that lane I emerged upon a memorable scene. Far and wide, beneath, the Elbe poured between its bridges. Some boats had just landed thousands of young children, who, returning radiant from their holiday in Saxon Switzerland, swarmed in a riot of color about the candy women on the waterside below, each with a yellow ticket strung about his or her neck.

A segment of delicate pink sun drifted low beside the opera-house, sending through the hoary arches of the Augustus Bridge a fainter film of rose to rest on the river surface. Haze-colored smoke floated from steamers made fast to the shore, bedimming the Museum's flat dome, the tower of the Court Church, and the piquant spire of the castle, toning its vivid patina down to the faint fawn color of the eastward waters, and mercifully veiling the Landesrat and the opera-house, the bronze tigers of which frisked before a mass of masonry impressive in the dusk. With the waning of day, the ripples before the old bridge turned imperceptibly to liquid bronze, as light as the western heavens, lighter for the dark masses of stone behind; while to the eastward, sky and water, both a deepening fawn, brought out the gay colors of the river traffic and the rainbow of costumes along the shore.

Following an old custom, I dined at the Belvedere, where an orchestra that might be the pride of any city was playing Wagner to an audience whose very forks were dumb during the music. The acoustics were perfect; the hall was a gem in simple white and gold, and I shall not forget the pleasure of looking over those happy, cultivated faces to where, through the colonnade, the evening haze was deepening to an intense blue upon the river and the distant heights of Loschwitz.

The moon was up over the Academy of Art as I left, and the benches under the trees of the terrace outside were filled with people raptly enjoying, with the faint music, the splashes of watery light reflected from the lamps of the other shore, the murmur of the running river, and the soft silhouette of Dresden's noble bridges and towers.

Watchmen were prowling about the porcelain acres by the Church of Our Lady, and it seemed as if heaven had rained upon that favored spot a double portion of straw and sacking. The very booths of the market-place, drenched in moonlight, were touched with mystery and a kind of grotesque beauty.

Dresden is essentially a city of pleasure — of fair, wide prospects, of hearty river life, of zest in nature and art. Even the public buildings cluster about the Elbe, much as the huts of the first settlers clustered.

A circle of Wendish herdsmen's huts on the right bank, a line of fisher-shanties on the left — these were the unlikely beginnings of Dresden in the sixth century. But the settlement lay at the only point in the river valley where a ford was practicable, tempting the Germans to settle on the left bank between the Wends and the swamps, or Seen, unlovely places that have long since disappeared, leaving behind only the names See-Strasse, Am See, and Seevorstadt. Indeed, the very name of Dresden is derived from the Slavic dresjan, which means „dwellers in the swamp-forest.“

We know that the Church of Our Lady was built in the eleventh century, that until the twelfth the right and left banks of the stream were called respectively „heathen“ and „Christian,“ that Dresden was first mentioned as a city in 1216, and that the original bridge was built in 1222. The market-place in the New Town across the river still bears traces of its original Wendish form, the Rundling, or circle of huts facing an inner space with only one exit, a primitive device for guarding the cattle of the community at night.

It was prophetic of Dresden's artistic destiny that the first Margrave of Meissen to reside here (1277— 88) should have been Heinrich der Erlauchte, who was mentioned as a fellow-Minnesinger by Tannhäuser and by Walther von der Vogelweide. Heinrich married an Austrian princess, who brought to Dresden a piece of the true cross. For this a chapel was added to the Church of St. Nicholas, where it was exhibited, together with another cross that came swimming miraculously down the Elbe; and these drew such a throng of liberal pilgrims that St. Nicholas's was rebuilt as the Church of the Cross and the old wooden bridge turned into one of stone in 1319. It is curious to know that this church and the Augustus Bridge are still under one financial management.

During four troubled centuries unwarlike Dresden suffered much, and did not become important until the reign of Frederick Augustus the Strong (1694-1733)— „August the Physically Strong,“ as Carlyle loved to call him.

A gilt, rococo king, clad discrepantly in a wig and toga, he strides a gilt horse in the New Town market-place, a weak variant of Berlin's monument to the Great Elector, facing, with a faint grin, his kingdom of Poland, for which he turned Roman Catholic. Resembling Louis XIV in feature, he strove to resemble him as well in trying to revive the golden period of Roman culture and to combine, in the Zwinger, all the elegant and useful features of Roman baths and palaces.

The Zwinger was intended to unite immense banquet- and dancing-halls with baths, grottoes, colonnades, pleasure-walks, rows of trees and pillars, lawns, gardens, waterfalls, and playgrounds — a fit place to display the pomp and circumstance of royal domestic life in the ostentatious spirit of the eighteenth century. It was planned to carry the Zwinger down to the river and finish it with an unexampled palace; but Poppelmann, the architect, was able merely to build the forecourt before the royal whim veered.

This fragment, however, with its seven pavilions and connecting galleries, is unique among buildings — „the most vivacious and fanciful stone-creation of Germany,“ as Wildburg declares. „The swift evolution of late baroque,“ he continues, „into the most joyous and airy rococo, the wondrous fusing of an almost Indian imagination with German solidity and Gallic coquetry, make a gloriously artistic whole.“

The first impression made by the Zwinger on a student of history is that „August the Physically Strong“ must have had in mind the housing of his famous three hundred and fiftyfour children, and he cannot help wondering whether the chubby stone infants that cluster on each pavilion can be family portraits. The various deities scattered among these riotous princes seem frankly amused at their situation. Here is a sincerer sportiveness, a less manufactured gaiety, than I remember in any other rococo. This joyful and frivolous ornamentation was destined to become the classical example of its school, and until to-day to mold the style of the Meissen porcelain, invented in Dresden by Bottger in 1709.

The Museum, built by Gottfried Semper in the style of the Italian Renaissance, connects the ends of the Zwinger. It contains the finest gallery of paintings in Germany, a collection ranking with those of the Louvre, the Pitti, and the Uffizi. It was made in great part by August the Strong and his son August II, who had shrewd agents in the Netherlands, France, and Italy. Even the Pope and the King of Sicily did their utmost to rob Italy of its treasures for them.

Their most fortunate find was the Sistine Madonna, bought in 1753 from the monks of Piacenza for twenty thousand ducats and a plausible copy. To smuggle the picture safely across the frontier, the conspirators painted it over with a wretched landscape. When the treasure arrived, the eager king had it hung in the throne-room; and seeing that the best light fell on the dais, he shoved the throne aside with his own hands, exclaiming, „Room for the great Raphael!“

Nothing could more vividly bring out the contrast between esthetic Dresden and militant Berlin. And this contrast was emphasized three years later when Frederick the Great seized Dresden, ransacked the royal archives, and sent poor August II in a panic to the Königstein, leaving his queen behind to face the Prussians.

This war ended the gallery's rapid growth, but it had already become the most noteworthy collection north of the Alps. As early as 1756, Winckelmann, whose genius had been awakened by this gallery, called Dresden „the German Athens,“ a name that never gained the popularity of Herder's epithet, „the Florence of the Elbe.“

On entering the gallery, one's first thought is for the great Raphael. There is a hypnotic expression in the Madonna's wide eyes, which the infinite promises of that childHood have struck into trance, mirroring all the possibilities of motherhood. This intensity of vision is only accentuated by the formalism of Santa Barbara and Pope Sixtus. With Raphael's ordinary work in my mind, I was heartily surprised, years ago, by a first view of the Sistine Madonna. It was much as if, in a vision, I had heard one of a row of simpering Perugino saints burst forth into a Brahms song.

It is a commentary on the contrast between the characters of northern and middle Germany that the Dresden Gallery is poor in the early paintings of historical interest, and rich in the golden periods — an exact antithesis to Berlin.

Here Correggio, with his tenderness and his deep backgrounds, is even more fully represented than at Parma. Here Paolo Veronese may be known best — the gay Paolo in all his superficial glory, with his joy in luscious brocades set off against the gleaming of Palladian architecture.

The canvases of Giorgione are always suffused with poetry and a dreamy music, but here the hour is immortalized when Aphrodite slept while Giorgione painted. Myriad-minded Titian is almost at his height in „The Tribute Money“ and „The Marriage of St. Catherine.“ Before the exquisite, miniature altarpiece of Jan van Eyck one forgets its size, as one forgets the blindness of some great musician when he is playing his best. And here hangs one of the chief canvases of Van der Meer, that rare realist who has but lately come into his own.

Rubens is most characteristic in the mad „Boar Hunt“ and the swirling and plunging of the „Quos Ego.“

There is a humor unusual with Rembrandt in „Samson's Riddle“; and three of the master's most subtle character studies are „The Gold-weigher,“ the portrait of an old man, and that of his wife Saskia. His school is even better represented here than in Amsterdam or The Hague.

It is natural that the German painters should be weaker in Dresden than the Italian and Flemish and Dutch; for the artistic charity of the founder of the Zwinger and the Court Church did not begin at home. Nevertheless, there are a few native master-pieces. The well-known JNIeyer JNIadonna of Hol- bein was held for centuries as the original until chance discovered the present Darmstadt picture in the junk-wagon of a Parisian peddler. His portrait of the Sieur de Morette was long thought to be a Leonardo, and that of Sir Thomas Godsalve with his son is one of the most notable portraits of his English period.

Though the modern gallery is small, it is extremely select, as befits the vicinity. It contains such well-known paintings as Menzel's riotous „Market- place in Verona,“ Hofmann's „Christ in the Temple,“ and the appealing „Holy Night“ by von Uhde.

An old traveler once declared that he preferred to investigate mountains from the foot, inns from the inside, and palaces from the outside. The wanderer in Germany soon learns this method, particularly with palaces; but a visit to the Dresden castle is a mildly amusing exception to the usual rule.

Its exterior is not forbidding, like the ordinary German palace, being enlivened with red tiles, yellow plaster, and a graceful green steeple; with Renaissance gables and, in the court, with round stair-towers which recall the fact that Arnold of Westphalia rebuilt it at the time when he was creating the Albrechtsburg at Meissen.

The bedchamber of August the Strong is large, and his throne-room, adjoining, is hung with pictures of Leda and Aphrodite. The rooms are not so overladen with ornament as to be unfriendly, and one can imagine people actually taking their pleasure in the festal hall. Pictures are there, to be sure, of the inevitable Kaisers, but they look almost docile, and are neutralized by such homely frescos as „Ring Around a Rosy“ and „Washing the Baby,“ an operation not unknown to those palace walls.

The Green Vault is a place that contains earth's greatest display of knickknacks, royal playthings, and jewels. There are exhibited an ivory frigate in full sail, Siamese Twins in ivory, and one hundred and forty-two fallen angels carved out of a single tusk. In a place of honor is a dish with an elaborate representation of the „Scarlet Woman.“ There are goblets made of ostrich eggs, a silver beaker from Nuremberg in the form of a young lady, and the Bible of Gustavus Adolphus. One may see vessels and trinkets made of every stone mentioned in the Book of Revelation. A „perpetual-motion“ clock represents the Tower of Babel, whereon perch eight town pipers blowing four pipes, three trombones, and a waldhorn. Then there are wonderful Limoges enamels, the masterpieces of the old German goldsmiths, and, as a climax, the Saxon crown jewels.

After so much touristry it was natural to loll on the waterside in the quaint „Italian Village,“ a row of houses once inhabited by the Italian workmen who built the Court Church, now a restaurant and rendezvous for all genial Dresdeners. There it was pleasant to rest over a stein, and watch the river seething by between the magnificent piers of the Augustus Bridge; to enjoy through half-shut eyes the ox-eyed roofs of the New Town behind their well-wooded gardens, and the concave towers of the Japanese House, which shelters the royal library. Pleasant also to watch the divers opposite (for half of Dresden lives in the water during the hot months) , and the party-colored stream of life above, pouring back and forth over the swift stream.

Alas! they had already begun to tear down the venerable Augustus Bridge, the symbol of Dresden and its finest monument! The small, picturesque arches, dangerous to the growing river traffic, were doomed to yield to wider ones, which, as the authorities promise, are to be quite as picturesque. But the artists wonder how many centuries it will take to win back the patina of those piers.

After the sharpness of Berlin and the flatness of Leipsic, Dresden's humor is refreshing. It strikes a nice balance between satirical Berlin and softhearted, gemütlich Munich.

There is nothing brutally downright about it: it proceeds by indirection. If the Dresdener wishes to condemn the suburb of Striessen, for instance, he declares that the very sparrows take in their legs when flying over it. The pleasantry of the lower classes is of the mildest.

„In which street is the goose cooked only on one side?“

„Don't know.“

„In the little Plaunscher-Gasse, for on the other side there are no houses.“

In the plain old Rathaus there used to be a motto which is still characteristic of this town of friendliness: „One man's speech,“ runs the motto, „is a good half-speech. Hear the other man's speech, too.“ The Dresdener does not interrupt. He is not puffed up, nor does he imagine a vain thing. He is almost as polite as the Parisian, with much of the Parisian polish and savoir-faire. He is never brusque. A Berliner would call an idler „lazy,“ a Münchener would call him „ideahstic,“ but a real Dresdener would intimate that he is „not quite industrious.“ Instead of „You 're a boor,“ he says, „The honored sir appears hardly to realize that he is not conducting himself properly.“ The inquiring stranger will find him an entertaining companion who will gladly see him to the suburbs and even arrange for him, with many apologies, any neglected item of dress.

The Dresdener is orderly, modest, and quiet even in his pleasures. The very policeman is not so impressed with his position as the ordinary Prussian lackey. The Dresdener is so gentle that his very cats look altruistic, and his sparrows will hop across your feet in any beer-garden. He is so amiable that I have often been tempted to withhold a tip, to see if I could draw as much as a sigh from that paragon of Christian virtues, the waiter.

But, despite these qualities, he does not lack critical sense, defining, for instance, the Secession school of painting as „art which, if you would be cultivated, you must like at all events — whether you like it or not.“

Because Dresden has the advantages of a large city with but few of its drawbacks, it is so popular with Anglo-Saxons as to have an English and an American quarter. It is rich in painting, sculpture, music, and architecture; has fine theaters and interesting personalities; is charmingly situated and within a short ride of Saxon Switzerland, the most attractive miniature mountain range in Germany: and yet the individual still counts among its half-million people — counts even to the verge of town gossip. Despite the size of the city, neighborliness and sociability flourish like the roses of the Zwinger; and any novelty like a horse-race or an Englishman in knickerbockers lays hold of the united civic imagination.

Dresden combines the advantages of the metropolis with the humanity of the village, and one can easily forgive it for outdoing Leipsic in credulity, servility, and greed for titles, and for falling behind its neighbor in business methods.

The best place to meet the Dresdener is on the Brühl Terrace, „the balcony of Europe,“ as it was once christened by an enthusiast. Its daisy-covered walls were a part of the fortifications before Brühl, the all-powerful minister of August II, in 1736, made them over into his private gardens.

It was thrown open to the public in 1814. From the waterside, passages may still be seen leading to the ancient dungeons, now used for the imprisonment of beer. On the corner, under the Belvedere, is a crude relief of the Elector Moritz being forced by a skeleton — a „bone-man,“ as the Germans say — to hand over the electoral sword to his brother August.

This very sword is now in the Johanneum, an old building in which the historical museum and the royal collection of porcelain lodge informally above the royal stables. The portal of the courtyard is the most representative piece of Renaissance sculpture in Dresden, a fusion of German and Italian motifs setting off a relief of the Resurrection.

In the center of the court is the tank where the royal horses were washed, and an inclined horse-path leads to the second story along an ivy-matted wall above which appear the picturesque gables and spire of the castle and the tower of the Court Church.

The historical museum is mainly devoted to the history of war. No other collection has given me such a vision of the glamour and romance of chivalry or the beauty of medieval weapons and armor. Here plumed knights joust as our childhood saw them in „Ivanhoe.“ Here one feels the poetry of battle as vividly as, in the arsenal at Berlin, one feels its scientific, realistic side. This is the Scott, that the Tolstoi, of war.

The royal porcelain collection is the largest and richest of its kind in Europe. Through the austerities of the early Chinese work one gradually approaches the melting harmonies of Japanese color, then drops back centuries to the first red German ware of Bottger, and on through the early whites of Meissen, and its colored imitations of the Asiatic, to the rococo of the Zwinger and the recent Meissen ware which imitates the royal Copenhagen. Faience and Italian majolica round a collection of which the most significant part is the group of giant vases in cobalt blue given to August the Strong in 1717 by old Frederick William of Prussia in exchange for a regiment of tall dragoons.

The Albertinum cannot compare in its ancient sculpture with the Glyptothek of Munich or even with Berlin's Old Museum; but the modern sculpture gallery is important and contains a collection of medallions even more exquisitely chosen than the larger collection in Hamburg.

I shall not forget my parting from Dresden. One of the gay steamers that ply up-stream dropped me to climb the heights of. Loschwitz for a last glimpse of the German Florence from this northern Fiesole. There it lay, checkered with patches of sunlight and looking almost mysterious through a delicate mist— that duomo, the Church of Our Lady, herding its flock of comely towers, a solid Protestant antithesis to the baroque brilliance of the Catholic Court Church.

There lay the city of pleasure in all its beauty, interlaced with silvery streaks of pond and river. And toward it, sweeping parallel to the mighty arc of the Elbe, ran a broader river of smooth green meadow-land fronting the villas of the opposite shore.

Backward the peaks of Saxon Switzerland were beckoning, but it was with an unaccustomed regret that I turned my face from art to nature.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

Dresden — Church of Our Lady from the Brühl Terrace. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Dresden — Porcelain Fair in the New Market, the Church of Our Lady on the left. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Dresden — Court Church and Castle as seen from the Elbe. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Dresden — Dresden from the left bank of the Elbe, the Queen Carola Bridge in the foreground, the old Augustus Bridge in the distance. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

alle Kapitel sehen