II. Berlin — the City of the Hohenzollerns.

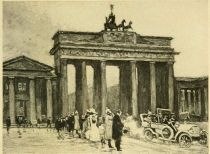

The rare Berlin sun bathed Unter den Linden and wrought happy effects among the columns of the Brandenburg Gate, lovely in its Attic repose against the May foliage of the Tiergarten. In the guardhouse on each hand the guard was undergoing inspection. Each private came stiffly up to his officer and whirled stiffly about, to show that he was uncontaminated by the great, dirty human world beyond the pahngs. But just as a spot was found on an unfortunate leg, a trumpet rang out from the Friedens-Allee, the watch before the gate yelled something in a superhuman voice, the officers, with protruding eyes, leaped hysterically through the door, and the soldiers tumbled after, presenting arms to the cloud of dust in the wake of the Emperor's automobile, which had whizzed, at the Emperor's speed limit, through the royal entrance.

The soldiers’ turned dejectedly back to inspection.

„Swine-hounds!“ cried a pale officer, „why could n't you do that quicker?“ And even the bystanders eyed them with reproach; for every citizen in the crowd had been a soldier himself, and knew that he could have managed things better.

The people were still glowing with the excitement and pleasure of having seen the Emperor, I had caught a glimpse of the familiar face as it flashed by — the keen eyes that seemed to look into the soul of every one of us, their hint of coldness and hardness corrected by the kindly lines about them; the straight, frank nose; the morose mouth, artificially enlivened by the grin of upturned mustaches, like the enforced jocularity of „The Man Who Laughs“; the determined, energetic, military jaw. This typical Hohenzollern face, coming and going like an apparition, suddenly lent fresh interest to a place which I had always found interesting. For, as I drifted down „the Lindens“ with the crowd, the question arose whether this modern, militant city, with its zest in commerce and diplomacy, in art and science, were not in many senses an em- bodiment of the Hohenzollern character.

A Frenchman once declared that Prussia was born from a cannon-ball, as an eagle is from an egg. And indeed it would be hard to find another German city with so few old buildings as Berlin and so little atmosphere. A Strassburg cathedral, a market-place out of Danzig, a row of Hildesheim houses, or a Breslau Rathaus, would be as out of place here as in an arsenal. Most of the Berlin architecture has as much color as a squadron of battle-ships in warpaint, and the little glamour to be found here is almost as well hidden as a pearl in a pile of oystershells. The city fairly bristles with weapons and militancy. Its statues, when they are not of mounted warriors with swords, or of standing warriors with spears, tend toward such subjects as Samson plying the jaw-bone of an ass, or hounds rending a stag. Painting, too, has been drafted into the service, and one sees so many military pictures in the public buildings that even the absurd portrait by Pesne of Frederick the Great in the Palais is a relief. For there Frederick, aged three, is only beating a drum, although a lance, a club, and what looks like a pile of cannon-balls, appear in the background.

But sometimes, when surfeited with this martial over-emphasis, I think of the terrible frontiers of Prussia and how well she has guarded them, reflecting that, if she had beaten her swords into plowshares, I should not now be enjoying the gallery or the Tiergarten, the Opera or the Krogl; and then I grow more reconciled to Berlin's eternal bristling.

Despite its many repellent qualities, however, Berlin has always had for me on every return an indefinable thrill in store; indefinable because I have never been able to account for its strange charm, its emotional appeal, as one accounts for the lure of other places. Reason declares it one of the least charming of cities, and yet we are enticed. The truth is that its genius loci, like its reigning ruler, is not to be gaged by ordinary standards.

Unter den Linden, the broadest street in Europe save one, is the principal stage for the drama of Berlin's brilliant and cosmopolitan life. Dorothea's unluxuriant linden-trees extend no farther than Ranch's monument to Frederick the Great, though Unter den Linden goes marching on, despite the anomaly, to the Castle Bridge. The hero, infor- mally sitting his charger in his cocked hat and with his trusty crooked stick, seems to dominate the situation as easily as in the stirring days of the eighteenth century. „In this monument,“ Rodenberg once said, „pulsates something of the monstrous energy of the Prussian state.“ And the Opern-Platz is in character with its leading figure. Carlyle wrote of him that „he had no pleasure in dreams, in party-colored clouds and nothingnesses“; and certainly there is little now before him to offend his sensibilities. There is nothing party-colored about this architecture. A bronze Frederick sits between a plain brown university and a plain brown palace; a severe brown Opera, embellished with fire-escapes, confronts an austere gray guard-house; while farther along, an angry arsenal bullies two sad-looking palaces, likewise in brown, all solidly built and with no unseemly levity.

One imagines the first emperor with his grandson in the famous corner window of his Palais, where he always stood to see the guard relieved, watching with sympathetic eyes the students (whom he was fond of calling his „soldiers of learning“) in the university across the way, that souvenir of Prussia's darkest hour, when, in 1809, she had lost to France everything west of the Elbe. In that crisis a handful of scholars approached Frederick William III with their project, and the enthusiastic king exclaimed: „That is good! that is fine! Our land must make up in spiritual what it has lost in physical strength.“ In this spirit such men as Fichte and Schleiermacher, aided by Wilhelm von Humboldt, founded Berlin University. And it is no wonder that, with a truly Hohenzollern rapidity and acquisitiveness, it has within a century gained 9.000 students and 500 teachers, and gathered such stars to its crown as Mommsen, Curtius, Helmholtz, Ranke, and Hegel. Its school of medicine is particularly strong, and attracts the young doctors of all nations, especially Americans. For Germany leads the world in theoretical, America in applied, medicine. But, in spite of our practical bent, Berlin possesses in the Virchow Hospital the most perfect institution of its kind, a group of thirty buildings built on the new pavilion system, which puts our leading hos-pitals to shame.

There is one local institution, though, untouched as yet by the imperial love of progress. I remember once crossing the North Sea with a Berlin student, and we fell to comparing our respective universities.

„There is, anyway, one point,“ he argued, „where we go far ahead of you. I talk of our library system. Yours is not to be mentioned, — how say you? — yours is not to call in the same expression with ours for celerity. Why, if you will order a book in the morning at eight, you may not infrequently obtain it before three in the same afternoon!“ This claim I afterward verified. But American methods will prevail in the new building which is being built next to the university. The old library,, with its spirited, curved façade, is one of the last monuments to the baroque spirit in Germany.

The opera-house was built by Frederick the Great as the beginning of a huge „Forum Fridericanum,“ a Prussian counterpart to the gigantic Saxon scheme of which the Zwinger Palace at Dresden was intended to be the mere foreshadowing. It is the home of that art for which the Hohenzollerns have always shown the most understanding, one nowhere else so fully represented as at Berlin — the national art of music. The Opera, the orchestra of which ranks second in the land, divides with the Royal Theater an annual subsidy of $ 225.000. Richard Strauss is one of the conductors, but even he has less authority there than the Emperor, who supervises in person the slightest details of execution and setting. A larger opera-house is soon to be built on the Konigs-Platz.

Berlin has an embarrassment of musical riches. Besides the excellent performances of the Philharmonic Orchestra, which may be heard for ten cents, the city averages twenty classical concerts daily during the season. There one may hear rare works, seldom given elsewhere, and the breathless audiences are filled with an almost religious fenvor of attention. They realize what we do not, that the hearer is almost as important a factor in the making of music as the performer.

The Zeughaus, or military museum, is the most Prussian thing in Prussia, and some one has said that this building is to Berlin what its cathedral is to an ordinary city. The facade is alive with spirited sculpture, and Schliiter modeled the beautiful masks of dying warriors inside. Here is one of the most brilliant and complete collections of armor and weapons in the world, while the best human touch is given by Napoleon's pathetic little old hat, guarded by sixty-eight wax soldiers, dressed in every Prussian uniform since the time of the Great Elector. The Hall of Fame is filled with bronze busts of Prussian men of valor, and with appropriate paintings of better quality than the usual battle-picture. The ruling passion of the Hohenzollern rages here ad libitum, and the impression is not weakened after crossing the Castle Bridge, which the Berliners call „The Bridge of Dolls,“ after its eight marble groups illustrating the education of the warrior, — poor things, all of them,— cold imitations of the cold Thorwaldsen.

The atmosphere of the Lustgarten is profoundly martial. In the center towers Frederick William III on his war-charger, gazing toward the castle, whereon stand figures of the late Emperor Frederick III as Mars, and of his father William I as Jupiter. Beneath their glances five armed princes of Orange guard the terrace, and two men in verdigris struggle with wild horses at the portal. In a lamentable position on the bank of the Spree looms Begas's monument to William I, the foremost among Berlin's military sculptures. Four delirious lions, crouching on heaps of arms, snarl at the four corners; colossal figures intended to represent War and Peace sprawl unhappily on the side steps, and the whole is surmounted by a group which must have suggested to Saint-Gaudens the idea for his Sherman monument. The helmeted hero of Sedan is led by a Victory whose two sisters drive quadrigas on the colonnade at each side — all in all an impressive and ferocious sight. Northward lies the cold, hard, hideous cathedral. Near it, topping Schinkel's noble Old Museum, more wild horses struggle with wild men, while, beside the beautiful, serene flight of steps, an Amazon and a warrior, both mounted, are forever trying to transfix a tiger and a lion, the latter by a sculptor of the savage name of Wolff. And finally, looking down the vista of Unter den Linden, that reach so characteristic of the far-seeing, purposeful Hohenzollerns, the clear-sighted catch a glimpse, past Frederick the Fighter, of a third quadriga and a fourth Victory, sublime on the Brandenburg Gate.

Save for some dim frescos in the porch of the Old Museum and for the green cupola of the castle, the Lustgarten suffers from Berlin's chronic dearth of color — a dearth that has driven the makers of cheap postal-cards to the desperate expedient of printing the black dome of the cathedral red and the gray steeple of the Memorial Church skyblue.

The Hohenzollern fondness for mottos finds vent on the cathedral and the castle, while the statues of the princes of Orange and counts of Nassau stand there dauntless and beautiful, like true Princetonians, over such sentiments as „Nunc aut num- quam,“ „Patriae patrique,“ and „Ssevis tranquillus in undis.“ These latest additions to Berlin's bronze elect are well conceived and executed, with more of mellowness and atmosphere than one meets with in earlier Berlin sculpture. They were evidently modeled with the inner eye turned toward King Arthur and his blessed iron company at Innsbruck.

The finest views of the castle are from the Burg-Strasse, across the river. Seen from a point opposite the cathedral, the northern facade of the venerable Hohenzollern home assumes an austere but very real beauty, lightened by the grace of the ivy-clad Apotheke, with its oriel. It takes time to appreciate this building, but it wears like a truehearted, steadfast Berliner after you have learned to discount his failings. Sometimes the plain, eastern facade is very friendly beyond the throng of barges along its water-front; and even the royal stables are a goodly sight from here on a sunny morning, topped by the Gothic spire of the Church of St. Peter.

But best of all is the view in June from 'the Elector's Bridge, with the bit of tree-embowered garden at the southeastern corner of the castle, the vines clothing the ancient walls to the very top, and trailing over the embankment into the water; with the monumental columns and portals of the southern fa9ade, and the green cupola coming out slightly above the mass with an inimitable effect, while Neptune's Fountain in the square throws rainbow mist about his glistening water-folk, and the Great Elector in bronze rides with a true Roman nobility on his bridge, coolly satisfied with the outlook. This is Berlin's greatest monument, and it seems almost a part of the castle itself, for both were largely the creations of the greatest of Prussian architects, Andreas Schlüter, and both are among the finest examples of baroque art in Prussia.

There is a suspicion of legend hanging about this bridge, for the story goes that Schlüter, on discovering that he had forgotten to fit the Great Elector's horse with shoes, jumped into the Spree and was seen no more. But, in spite of this defect in equipment, old Frederick William, every New Year's Eve, jumps his horse over the heads of the fettered slaves and rides as light as a shadow through the city to find how the seed of his sowing has thriven and how the young Hohenzollerns have been upholding the family record.

In 1750, when Frederick the Great had finished his new cathedral, the bones of all his ancestors since Joachim II had to be shifted from the ancient vaults to the new. „Frederick, with some attendants, witnessed the operation,“ writes the historian Preuss. „When the Great Elector's coffin came, he made them open it; gazed for some time in silence on the features, which were perfectly recognizable, laid his hand on the long-dead hand, and said, ‘Messieurs, celui-ci a fait de grandes choses.’” How like the famous scene at Potsdam a few decades later, when Napoleon stood by Frederick's leaden coffin, saying, „If this one were alive, I should not now be here.“

The castle was begun in 1443 by Frederick Irontooth, the second Hohenzollern elector, but the oldest remaining part, the round tower near the Elector's Bridge, called „The Green Hat,“ was built by Joachim II in 1538.

The interior is not enlivening. You ascend a long, inclined plane of brick called the Wendelstein, and shift into felt overshoes, wherein you shuffle through an interminable line of flashy festal chambers. There is the Red Eagle Room, with its wooden replicas of the silver melted up by Frederick the Great in his dire need; the Knights' Room, with a chandelier beneath which Luther stood at the Diet of Worms; the Room of the Black Eagle; the Room of Red Velvet; the White Hall; and so forth. The only unoccasional paintings in evidence are a few third-rate Italians outside the White Hall, and these, as the guide declared, are soon to come down. The only old masters are two Vandykes, which look quite appalled in the barbarous wastes of the picture-gallery. And one longs for a glimpse of the famous Watteaus, hidden away in the Emperor's private suite.

There are other views from the Burg-Strasse almost as engaging as those of the castle. It is good to stand near the William Bridge and see, beyond the flapping green eagles of the Frederick Bridge, the National Gallery riding high above its foliage, which allows a glimpse of the impressive double stairway and the warm browns of the Corinthian façade.

It is a startling adventure to find a barely tolerable view of the cathedral, a building which, as Lübke declares, „looks as if it had been taken from a box of toys.“ This welcome experience did not come to me until my sixth visit to Berlin, and even then I was guided by a painting of Alfred Scherres, seen on the way. But the painter had undeniably found a spot beside the Circus Busch where it is pleasant to linger at twilight or on a misty autumn morning.

In the foreground, on a flotilla of roofed-over barges, are the lively colors and sounds and the sweet odors of a pear market. Across the dusky, sparkling Spree the tree-fringed colonnade of the National Gallery leads the eye to the rising and falling rhythm of the Frederick Bridge, whereunder the river winds, gray and gleaming, past the vivacious cornice of the stock exchange. And above the flowing lines of the bridge rises, with its repulsive details mercifully hidden by the mist, the huge, dark dome of the cathedral, really noble and impressive for once, and composing finely with the cupola of the castle.

To remember that the cathedral cost almost $ 3.000.000 and covers a larger area than Cologne minster, and then to look at the cathedral, is an experience that makes the heart sick. True, it expresses in a way the present character of Berlin — its cold asperity and self-consciousness. But one wonders whether a beautiful church in its place might not be doing more to make the city human and lovable. It was erected between 1894 and 1906 to take the place of the former pitiful little cathedral, which possessed no architectural distinction, and was sadly dwarfed by the majesty of the castle on the one hand and of the Old Museum on the other. It is supposed to express the present Emperor's architectural taste; for it is said that he made many changes in the plans, and signed them „William, architect.“

One turns away with relief to watch the children playing about the great red granite basin in the Lustgarten, and to marvel at the costumes of the Spreewald nurses— the short, scarlet, balloon skirt overspread by a snowy apron. There is a mere pretense of sleeves, and the gay neck-cloth is set off by a brave, triangular spread of linen head-dress, fringed five inches deep.

The museums of Berlin fortunately show few traces of the influence of the Hohenzollern taste in art. For they have as their Director- General Dr. Wilhelm Bode, whose fine feeling and determined will have here been almost supreme. Thirty years ago they were poverty-stricken, but the genius of Bode has made them one of Berlin's chief glories; and that is true not only of the art collections, but also of the Agricultural Museum, the Arts and Crafts, the Costume, Ethnological, Hohenzollern, Marine, Mining, Natural History, Postal, and Provincial museums.

The statues of the Old Museum consist chiefly of late Roman sculpture of no special importance, but „The Praying Boy,“ an early Greek bronze, would be a worthy companion to the most famous statues in Munich's Glyptothek. Here are superb collections of antique gold and silver, of Greek and Roman gems and cameos, vases, and terra-cotta statuettes.

A passage leads across the street to the New Museum, a homely building devoted mainly to Egyptian art and plaster casts. But its print collection is the richest and best arranged in Germany, and particularly strong in the works of Dürer and Rembrandt. Best of all is the set of Botticelli's illustrations to the „Divina Commedia,“ so vividly described by Arthur Symons in „Cities of Italy.“

In the National Gallery, Hohenzollern influence becomes apparent in the prominence of huge military scenes and royal portraits. But, with all its faults, the collection ranks next to those of Munich and Dresden as an exhibit of modern German painting. It is rich in Menzel and Bocklin, in Defregger and Lenbach and Marees; while, of the younger generation, Kuehl, Von Uhde, Leibl, Hans Herrmann, Skarbina, and Liebermann are well represented. The sculpture stands far behind the painting, but Max Klinger's „Amphitrite“ is a work in colored marbles that takes rank with his Beethoven in Leipsic.

It was an odd coincidence that the altar of Pergamon should have been unearthed by a German and sent to found a Pergamon Museum in warlike Berlin. For the frieze depicting the battle of the gods and the giants is not only our most nearly complete relic of Greek sculpture, a worthy mate to the Elgin Marbles, but it is also our fiercest piece of ancient plastic fighting.

The Kaiser Friedrich Museum should rather be called the Bode Museum, for it is a monument to the genius of its director. A few weeks before the day set by the Emperor for its official opening, Dr. Bode was taken seriously ill. But from his bed, with the aid of photographs and water-colors, he actually directed the furnishing and decoration of the entire building, the hanging of the pictures, and the arrangement of the sculpture, finishing his task within the time appointed. It is due to him that the gallery ranks third in Germany and that it is the first in equipment and arrangement. Indeed, among the collections of the world it is second only to London's National Gallery in the balance and completeness of all the schools of painting. Bode's idea of placing Renaissance sculpture among the pictures is brilliant, and is being wisely adopted in other galleries.

Space allows a mere word of description. The most important works of the old Netherlandish schools are the famous Ghent altarpiece by the Van Eycks, and the „Nativity“ by Van der Goes; of the old German school, Holbein's portrait of Gisze and Dürer's of Holzschuher, two of the best known of all German pictures. With their Fra Angelicos, Botticellis, Signorellis, Masaccios, and Da Forlis the elder Italian schools are more complete than the Renaissance, and more characteristic of the serious, scholarly Prussian collectors; but the Renaissance boasts four Raphaels, the „Fornarina“ of Del Piombo, a masterpiece of Del Sarto, Leonardo's „Ascension,“ and marvelous portraits by Giorgione and Titian. The later Netherlandish schools are specially rich in Rubens and Vandyke. Here are the largest collections of Rembrandt and Hals outside of St. Petersburg and Haarlem; while, among the Spanish canvases, are Murillo's most satisfying religious work and a famous Velasquez portrait. The collection of medieval and Renaissance sculpture is the most complete of its kind in the country.

This gallery stands at the head of the Spree Island, and on two of its three sides the windows give on the water. There is a peculiar charm in watching the unpretentious, old-fashioned waterway slipping quaintly through the city of blood and iron, of science and hard thinking, of peremptory officialdom and rapid transit. While the buildings and streets of Berlin remind one everywhere of the recent kings and emperors, the Spree still keeps a hint of the day of Irontooth, who refused the crown of Poland for the sake of old-fashioned righteousness; of Albrecht Achilles, who leaped alone over the walls of Grafenburg and kept five hundred armed men at bay until help came; of Joachim Nestor, the astrologer; and of the Great Elector, who, watchful above the river, still tries to guard the city's oldest part from a too ruthless modernity. And this is only fair, for he started the mighty movement wliich has made Old- World romance exotic in Berlin.

Rude barges filled with timber or enameled bricks are poled laboriously up and down the shallows by patient men with low brows and dark skins, descendants, perhaps, of the original Wendish inhabitants of Brandenburg Mark, figures that sweep the imagination back to the time when Henry the Fowler stormed the heathen fort of Brannibor, long before „Wehrlin,“ „the little rampart“ in Bo-Russia, or „Near-Russia,“ began to show symptoms of growing up into Berlin, the capital of Prussia and of the German Empire.

Old Kölln, the island in the Spree containing the castle, the cathedral, and the principal museums, was first mentioned in 1237, seven years before its neighbor, Old Berlin, eastward across the river. The sister towns were of small importance, and there was not so much as a ripple on the surface of history when, in 1411, they both came under the control of Frederick Irontooth. Johann Cicero made Berlin the permanent Hohenzollern headquarters in 1488, and two centuries later the Great Elector laid there the foundations of modern Prussia.

The Fischer-Strasse, running southeastward from the Kolln Fish Market, contains some surprises for the adventurer, and the Nussbaum restaurant will give him a thrill, with its genuine tree, its sharp, picturesque gable, and the hint of Renaissance halftimber wall peeping forth behind it.

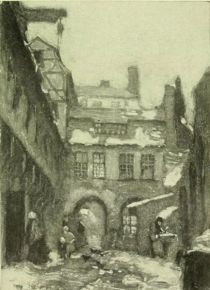

But the part of Berlin that stands alone in its atmosphere of romantic age is the Krögl. From the Fish Market you cross the city's most venerable bridge, pass the Milk Market, and turn down a narrow alley between tall, old-fashioned houses, the plaster peeling from their poor fronts, but with flowers and vines in the windows — an alley with a charming roof-line, which bends gracefully down toward the river, where boatmen, their poles braced against a pile, walk their boats up-stream with a curious effect. It is good to find water-grasses actually growing at the foot of the Krogl, a strange sight within the limits of this stern city. On one worn wooden portal one notices a remnant of the beautiful iron tracery of the Renaissance. You pass through an arch by the waterside into a more picturesque alley. On one hand is a house the upper story of which projects as do those in the streets of Brunswick and Hildesheim, but its corbels must be in the real old style of vanished Berlin, for they are unique. And this house actually lurks in the heart of the German capital opposite a wall blessed with a blind colonnade and the rich patina of ages. Beneath another arch you pause to look through a doorway into a dusky hole where three Rembrandtish broom-makers are dipping yellow straws into a pot of pitch. The glare of charcoal is on their pale, worn faces and dark beards. Two doves coo on the perch just outside the tiny smoke-blackened window. Hasten, traveler, oh, hasten, if you would enjoy the last of old Berlin! For the Krögl may soon be condemned by the same power that periodically scours the statues in the Sieges-Allee.

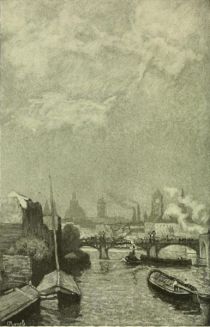

A sunset on the Spree, seen from one of the upper bridges, is well worth while. The traffic teeming on the glassy, rosy surface where it broadens into a wide basin, the bridge-lights stabbing the water between boats, the irregular old façades of the right bank backed by the massive tower of the Rathaus and the twin spires of the Church of St. Nicholas; the bulk of the Provincial Museum, the domes of cathedral and castle, — all these compose in the half- light into a picture containing more of the elements of romance than one had dreamed that the city possessed.

Only three of the old churches, all begun in the thirteenth century, are noteworthy. The choir of the Cloister Church is Berlin's most interesting bit of medieval architecture. The Church of St. Nicholas contains monuments of every period from late Gothic to the „Wig Time,“ as Germans love to call the weak classical reaction late in the eighteenth century; while St. Mary's is chiefly remarkable for a Gothic fresco, „The Dance of Death,“ and for the rude stone cross outside, erected in expiation of the lynching of Provost Nikolaus of Bernau in 1325.

From these remnants of medieval Berlin, past the beauty and peace of rare canvases and marbles, the Spree flows direct to the turmoil and fierce energy which the Friedrich-Strasse pours over the Weidendamm Bridge. This street is the main channel for Berlin's notorious night-life, which eddies about the Central Hotel and its vaudeville „Garden.“ The Café Monopol, near by, is a rendezvous for literary bohemia, and the Café Bauer, at the crossing of Unter den Linden, is the cosmopolitan resort par excellence. In Tauben-Strasse and the adjacent cross-streets lies the „Latin Quarter,“ full of Moulins Rouges and Bavarian hostelries, of ball-houses, variety-shows, and small, select cafés that open at two in the morning. A reckless spirit is the mode here, and one often sees this favorite quatrain on the beer mats:

Das Leben froh geniessen

Ist der Vernunft Gebot.

Man lebt doch nur so kurze Zeit

Und ist so lange todt.

(„Enjoy your life, my brother,“

Is gray old Reason's song.

One has so little time to live

And one is dead so long.)

The Latin Quarter's frivolity is almost overshadowed by the dignity of the Gendarmen Markt, the poor twin churches of which were capped by the architect of Frederick the Great with impressive cupolas, and now compose finely with the massiveness of Schinkel's Royal Theater. These churches, the exterior and interior of which are out of all relation to each other, are good types of the insincere Wig style. The market is particularly effective with the moon riding high between its cupolas and lighting Begas's marble monument to Schiller, a brilliant but heartless work. Two tablets announce that Heine and Hoffmann lived in this square.

The Leipziger-Strasse, the southern boundary of Berlin's most interesting section, is the main business street. Its store-palaces remind one that Berlin is the leading commercial and railroad center of the Continent, and take the mind back along the line of shrewd, businesslike Hohenzollerns who have brought this about. It is no freak of chance that placed the stock exchange opposite the castle and cathedral, or that placed the Ministry of War and the Herrenhaus in the Leipziger-Strasse. For much of Prussia's political success is due to the fact that Berlin is the chief market for money, grain, spirits, and wool. Until recently the English have supposed that they had a monopoly of European business talent; but now Berlin's rapidly growing industries are making England and America look to their laurels in iron-founding, the manufacture of machines, railroad materials, wagons, weapons, electrical supplies, and in the chemical and textile industries. And the city knows how to harmonize the practical with the esthetic; Wertheim's beautiful department store was built by the royal architect of museums, Alfred Messel, while the architecture of the Rheingold, near by, compares favorably with that of any American restaurant.

From this commercial street, Wilhelm-Strasse leads past the palaces and gardens of the Chancellor, the Foreign Office, the ministers, and the English Embassy to Unter den Linden. In the quality, though not in the quantity, of its activities, Wilhelm-Strasse is considered the diplomatic center of Europe. It is a monument to the ruler who, in spite of his inherited instincts, has preserved the peace of the Continent for twenty years.

The masses of marble in memory of Frederick III and the Empress Victoria, erected by William II outside the Brandenburg Gate, are regarded with dismay by artistic Berlin, as is the Column of Victory in the Königs-Platz, and to a less degree the Reichstag, whose gifted architect, Paul Wallot, was hampered by imperial collaboration. The exterior lacks unity, and the sculpture is monotonously militant; but the interior is a masterpiece of arrangement.

Hamburg's mighty monument to Bismarck dwarfs the Berlin bronze before the, Reichstag both in bulk and in spirit; but, on each side of it, the mermen and the fisherfolk are delightfully un-Prussian interludes, while the hawthorns about the Column of Victory add, in June, a grateful glow of color to colorless Berlin.

In the Sieges-Allee, William II hit upon a capital idea, which does credit to his love of education and to his pride in his forerunners. But here again it is recognized that the Emperor fell short, and his family feeling came out too aggressively, — worst of all, that he made the old mistake of fettering the individuality of his artists, so that there are few works of genius between the Column of Victory and the Roland Fountain, like Schott's „Albrecht the Bear,“ and Brütt's „Otto the Lazy.“ There is, by the way, a popular belief that the latter comes down from his pedestal at night and goes to sleep on the stone bench. And this is the pleasantest thing I have heard the Berliners say of the Sieges-Allee, which they have christened „The Avenue of Dolls.“ One schoolmaster, however, is said to have set his boys a theme on „The Leg-attitudes of the Hohenzollerns.“ The thirty-two monuments are too close together. The formal recurrence of standing ruler, two Hermes of eminent men, and a semicircular bench grows monotonous; and it would have been more fitting to have put the warrior family into bronze instead of brittle white marble. Yet in view of the conditions under which the artists worked the average of individual plastic achievement is high.

It is not generally known that the Tiergarten is the private property of the Emperor, and is a remnant of the ancient hunting forest of the Hohenzollerns, which once extended to the castle itself. It is so full of sculpture that the people jokingly call it the „Marmora See,“ and deny that there is any room for another piece of marble; yet some of the monuments, like those to Wagner and Queen Louise, are excellent.

Although it is hard to find a spot in the Tiergarten free from the sound of cabs and trolleys, yet it is to me one of the most delightful of city parks. Its chief charm lies in the beauty of its venerable trees, in the many ponds and streams filled with water-fowl, in the flowers and shrubs, and the constantly changing delight of its vistas. On coming here from the tastelessness of the Sieges-Allee, one is impressed with quite another phase of the Hohenzollern character— its genuine love of nature, merely hinted at in the Tiergarten, and which finds a fuller expression in Potsdam.

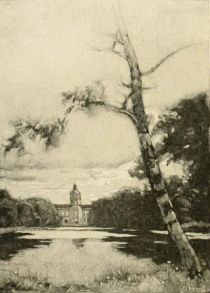

There is another park which is quieter, simpler, more idyllic— the grounds of Charlottenburg Castle. You pass the Technical High School, a model of its kind, and, as you walk westward, the people seem to grow friendlier, the houses older, and you see an occasional alley or court that is almost picturesque. Color creeps imperceptibly into the architecture, and the castle, with its high, graceful dome, is in a warm orange tint that reminds you of Sans Souci.

Back of it, in a lengthy line, stand busts of Roman emperors and their wives, with their usually official features relaxed, as is proper on a suburban jaunt. The grass grows long with a delicious informality in the half-neglected grounds, damp and delightful as though it knew nothing of officialdom. One feels that one may even venture to set foot on it without starting Prussian fulminations. And one likes to think of those royal dead lying in the lovely mausoleum amid this red-tapeless nature after their etiquette-trammeled lives.

The Zoölogical Garden at the southwestern corner of the Tiergarten is one of the most complete and best organized collections of animals in the world. But the human animal, here as everywhere, is the most interesting exhibit. The „Zoo“ seems always full of Berliners, and is an excellent place to study that remarkable species.

When I speak of the Berliner, I do not mean the highest stratum of Berlin society; for the gentleman and the gentlewoman are fairly constant types the world over, and, in judging the average quality of the people of any metropolis, one finds the cul- tured classes forming such a slight proportion of the whole as to be almost negligible.

There are, of course, many citizens of Berlin who are represented in no detail of the following picture. It is a composite portrait of that well-known personage whom the young clerk, fresh from the provinces, sets about imitating; the person whose origin is recognized the moment he enters any European cafe; the person with whom the stranger in Berlin has almost exclusive dealings.

The studies for this portrait were gathered not alone from personal observation during repeated stays in Berlin, but also from a consensus of the opinions of many Berliners and other Germans and foreigners, and from the voluminous literature of the subject.

The Berliner inclines to imperial standards in appearance and character, very much as his city does. A smooth, determined chin, a daunting glance, a right noble pose, a rapid stride, are all the mode. An upturned mustache has recently been de rigueur, and one notices with a smile that even the bronze mermen on the Heydt Bridge possess the imperial „string-beard.“

One of the Berliner's most trying characteristics is his superiority. He has known the latest joke at least ten years. Do not try to tell him anything or to strike from him the least spark of enthusiasm; for news is no news to him: he was born blase. His eleventh commandment is, „Let not thyself be bluffed“; his life motto, „Nil admirari.“ In conversation he instinctively interrupts each fresh subject to deliver the last word upon it, and to argue with him is to insult him. Here it is easy to trace the didactic influence of the ruler who devotes much of his spare time to the instruction of genius.

There is something cutting in the Berliner's speech. Perhaps Voltaire's influence on the great Frederick, the critic-king, started this dreadful habit, which seems to grow with indulgence. It is a curious coincidence that the first performance of Goethe's „Faust“ should have been given in Schloss Monbijou, the home of the Hohenzollern Museum, for it would almost seem as though the Berliner s had modeled their daily speech after the caustic, sneering style of the engaging villain in that drama.

They have little humor, but much wit of the barbed, barracks variety. And their target is the universe.

Of a cross-eyed man they say: „He peeps with his right eye into his left waistcoat pocket“; of one with a large mouth: „He can whisper into his own ear“; of a pock-marked person: „He sat on a canebottomed chair with his face.“

Bismarck often showed this kind of wit, as, for instance, in the letter written in 1844 from Norderney:

Opposite me at table sits the old Count B . . . , one of those shapes that appear to us in dreams if we are not feeling well, a fat frog without legs, which before each bite tears open its mouth like a sleeping-bag down to the shoulders, so that I hold on giddily to the edge of the table.

This sort of thing is telling, but it hardly makes for brotherly love, and a little of it goes a great way. Humor implies sympathy; wit, the opposite; and this exclusive cultivation of wit is a product of the ancient reserve and Ungemütlichkeit of the North.

In the „Germania,“ Tacitus describes the North German's coldness and reserve, his love of solitude, his custom of settling far from high-road and neighbor. And he has changed little at heart since Tacitus. Many of the Hohenzollerns have possessed this quality, but none more than Frederick the Great. „He had,“ wrote Carlyle, „the art of wearing among his fellow-creatures a polite cloak- of-darkness ... a man politely impregnable to the intrusion of human curiosity; able to look cheerily into the very eyes of men, and talk in a social way face to face, and yet continue intrinsically invisible to them.“

The Berliner is unapproachable and outwardly cold. He is prudish about showing emotion, and considers the gemütlich Bavarian effeminate. True, allowance must be made for the disappearance of human qualities among the people of a metropolis; but Berliners are far less friendly than Parisians or Londoners.

The most merciless critics of Berlin, however, are its own citizens.

„We are become such dreary people,“ writes Naumann, „that we are almost dead of inner cold. We are rich in knowledge, and beggars in feeling. We are become too withered for boundless offering, for love unto death, for sacrifice and devotion, for prayer and eternal hope. We have been taught that we must be sapless, heartless halfmen if we would stand on the summit of the times. Alas! this barren, this parched, this pitiful civilization!“

Aggressiveness has ever been a leading Prussian trait, and without it the history of Europe would have been quite different. But this quality has often shown to poor advantage, as when Frederick William caned the shrinking Potsdam Jew, exclaiming, „I 'll teach you to love me!“

The city is alive with uniforms. The citizen brings the manners of the camp into his daily life, and, in lieu of an epaulet, goes about with a chip on his shoulder. In the shops it is common for the clerk to inquire sneeringly, „Is that all you 're going to buy?“ And presently those trite old phrases about „the world's broad field of battle“ and „the bivouac of Life“ begin to take on, for the stranger, a little more vital meaning.

In the Museum of Arts and Crafts I had an experience characteristic of the city. A pile of five- cent catalogues lay on a table in the main hall. I thought of investing, but my hand was still on the way when, from fifty feet behind, came the roar of a guard: „Don't touch! Those cost money.“ There is a favorite Berlin motto apropos of this quality:

Bescheidenheit ist eine Zier,

Doch kommt man weiter ohne ihr.

(Humility has charm, no doubt,

But one can get ahead without.)

Though the Berliners are their own most extravagant critics, they will not tolerate disparagement from any one else. The other Germans call them „aufgeblasen,“ which is to be interpreted, „pneumatic.“ A popular story is apropos:

„Ah,“ cried the provincial, „behold the beautiful full moon!“

„Pshaw!“ sniffed the Berliner. „That 's nothing at all to- the full moon in Berlin.“

Their esthetic standards are reflected in the homes and the dress of the people, and not long ago Diotellevi, an Italian critic, maliciously wrote, „Their ideal in domestic architecture is that of the universal exposition.“ Over-ornamentation, and discords in colors, materials, and styles are the fashion. In this connection A. O. Weber, the most popular of recent German satirists, has written somewhat as follows:

Berlin 's a place that makes me laugh —

Marble and plaster, half and half;

A city that reminds me ever

Of some sublime, some howling swell

Who wears a smart black frock-coat never

Without high rubber boots as well.

But the beautiful new statues of the princes of Orange show that the taste of official Berlin has improved of late. And that the taste of the Berliner has made a corresponding advance is evident in the charming new cement houses of Charlottenburg, in the great retail stores of the Leipziger-Strasse, and in the villas of Grunewald.

Finally, before turning to the more agreeable side of the Berliners, it must be remarked that they are unconscionable martinets. A socialist once declared that it took half of all the Germans to control the other half. This is truer of Berlin than of any other place I know. There even the street-sweeper, highly conscious of his officialdom, wields his broom like a scepter. The sign Verhoten! (Forbidden!) is more common than the posters of America's favorite articles of commerce in New York. The city is superbly governed, but with a nagging, tedious paternalism that is at first amusing and then oppressive to one whose ancestors never formed the habit. There is a true story of a Berlin conductor and a lady who was standing with a lap-dog in her arms.

„Sit down!“ cried the conductor.

„But I prefer to stand.“

„Sit down!“ he shrieked, forcing her into a seat. „Lap-dogs must be carried in the lap.“

Because their unpleasant qualities are on the surface, and their admirable ones are below, the Berliners do a grave injustice to the rest of Germany. Many foreigners go first to the capital, are repelled by the people they first meet, and hasten on to France or Italy with the idea that all Germans have corrosive tongues and the manners of a drill-sergeant. Whereas there is no wider difference in temperament between the people of Naples and those of Warsaw than between the citizens of Munich and the citizens of Berlin.

There is a story of a Thuringian woman who was asked if she had seen Berlin. „No,“ she replied; „I have never been abroad.“

In fact, their countrymen regard the Berliner s with almost as little sjinpathy as though they were foreigners. In Leipsic the word „Prussian“ means „angry“; in Thuringia, „exacting“; in Altenburg, „in strained relations“; in Erfurt, „obstinate“; and in South Germany, „raging.“

Yet when one comes to know the Berliners, it is not hard to discount these irritating, superficial traits and to love the people for the splendid, enduring qualities that lie so deep. What was said of Bismarck might apply to the typical Berliner. He is like a flannel shirt that scratches at first, but in the mountains you can wear no other. The Hohenzollerns have worn so well that they have, as a rule, been more beloved in old age than in youth.

It takes years to make a friend of a Berhner, but then you have a friend indeed. His chief virtue is his uprightness, his sturdy sense of duty. When the Great Elector was urged in turbulent times to marry, he responded, „My dagger must be my bride until this task is done.“ Frederick the Great said: „It is not necessary that I live; but it is necessary that I do my duty.“ The first Emperor had „no time to be tired,“ and his noble Empress Augusta was fond of saying, „Empires pass; God alone remains.“

Principles like these are the foundation of the Berliner's character. No other city in the world has such an honest and efficient administration. Of an annual municipal report Professor Richard T. Ely writes, „One finds it difficult not to believe it a description of some city government in Utopia.“

Over forty-four thousand citizens take part without reward in the administration of affairs, and these include the foremost Berliners. There is no body of men more public-spirited, more really benevolent, more imbued with the idea of progress. And over 2000 of the 2,000,000 inhabitants are members of local charity commissions which have discovered how to help the poor without imposing degrading conditions.

In the gift for organization and in executive talent the Berliners rival their rulers. „No European court,“ writes Bryce, „has been more consistently practical than that of Berlin. . . . Her rulers have eschewed sentimental considerations themselves and have seldom tried to awaken them in the minds of the people. . . . Ever since the Reformation the Hapsburg princes and their policy have been regarded with aversion by the more intelligent and progressive part of the nation; while Prussia, recognized from the days of the Great Elector as the leading Protestant power, naturally became the repository of intelligence, liberty, and enlightenment.“ So it is not surprising that they should have borne a leading part in forming the Tariff Union of 1833, in making education compulsory, in agrarian reform, in the conscription movement, and in the unification of the German Empire.

„Berlin is new, all new, too new,“ exclaimed Huard in his caricature, „Berlin comme je l'ai vu,“ —“newer than any American city, newer than Chicago, which is the only city comparable to it in the prodigious rapidity of its development.“ Indeed, in freshness, in youthful energy and initiative, the Hohenzollerns and the Berliners are more like Americans than like Germans. And in the matter of municipal comfort they have left every one else far behind. Public utilities are managed by the city, and are such models of efficiency, cheapness, and profitableness as to make an American sick with envy. Every street is thoroughly cleaned in the small hours of the night, and the humblest pavements are as immaculate as the asphalt of Unter den Linden. It is possible that such splendid re-sults might have been reached in a kindlier way; but after years in Berlin the advantages of the system neutralize one's irritation at being overgoverned.

The Berliners have inherited their masters' love of independence — a reason for the periodic friction between ruler and subject. This quality of the North Germans (whose ancient names were derived from words meaning „sword“ and „warrior“) made them the most obstinate opponents of the Roman rule, and led them to embrace Protestantism long before the rest of Germany. And in Berlin to-day the Protestants outnumber the Roman Catholics by nine to one.

Like their Emperor, the people of Berlin have an earnest desire for culture, and, like him, are constantly trying to make encyclopedias of themselves. Though the city has produced few artists of the first rank, it has been more fortunate in begetting scholars and philosophers, and has always succeeded in inducing genius to come and work in its unfavorable atmosphere, although such men as Goethe and Mendelssohn have denounced the anticreative spirit of the place.

Though the Berliners are such virulent self-critics, they are their own most devoted adorers. So it is not strange that they abuse in set terms the princes after whom they have patterned — and love them as their own souls. It is touching to see the devotion in the faces of the crowd as the Emperor every morning leaves the Chancellor's palace, or as he drives in Unter den Linden down an avenue of hatless subjects. I recollect a characteristic scene. The Emperor was taking the air on foot, followed by two adjutants, the Empress trotting to keep up with his vigorous pace. Lined along the curb ahead were forty droshkies, their rabid, anti-imperialistic, socialistic drivers drooping on their boxes or lolling inside. The first man to spy his Majesty gave a sharp hiss, and the whole line, with more alacrity than I had ever before noticed in them, leaped to the ground and devotedly swept off their shiny, waterproof hats, while the Emperor, greatly amused, strode along, saluting as regularly as though he were chopping a cord of wood.

The damp, misty climate has undoubtedly had a disagreeable effect on the character of the people, for the city is in the latitude of Labrador and lies low, near that fog-breeder, the Baltic.

But a mellow, perfect bit of autumn weather creates the illusion, by sheer force of contrast, that Berlin is one of the most ravishing places in the world. One can dream in the parks or wander along the streams, filled with the dolce far niente of Fiesole or Sorrento. And the people, the harsh, corrosive Berliners, seem suddenly to secrete a little of the milk of human kindness. On such a day I have seen a group of wry-faced Prussians run into the street and help a weak horse to get his load over the ridge of the Frederick Bridge. Such moments are wonderfully effective against their somber background, and the most engaging sight I have ever seen in the city was that of a little green bell-boy in his brand-new uniform, being kissed on the sly by his dear mama behind the Palace Hotel.

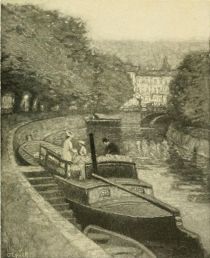

After a day of Berlin's best weather, the sunset along the Landwehr Canal is beyond praise. From the confusion and din of the Potsdamer-Strasse I came out upon a scene at the bridge as unreal as a vision— a suddenly flashed symbol of the good, true heart of Berlin.

I shall never again look with a careless eye upon the Potsdam Bridge after having seen that sky flaming behind it a deepening crimson. And when I stood on the Cornelius Bridge, watching in the unrippled surface the inverted pyramids of rosy and pale-blue sky framed by the dusky softness of the leaves; when I saw a curl of pale-blue smoke rising from an apex broken by a single magnificent tree, as though the sun itself were smoldering away, and, in the watery foliage, two high lights, picked out by the arcs on the bank, I praised God for letting His great out-of-door loveliness into the heart of that self-contained, repellent city.

Framed by the trees the cold, Romanesque, Berlin-like spires of the Memorial Church took on a more than earthly glamour. I walked downstream to watch the moored boats, never so pic- turesque as then; to contrast the Zoo's broad blare of yellow light with the radiance dying in ever fainter bars of azure, rose, and robin's-egg blue above the luscious curve of the bank; to enjoy the pronounced splashes of liquid light reflected from the bridge behind.

A launch puffed into the sunset with a jet of creamy smoke, sending the brazen ripples vibrating to the rhythm of the sensitive, beauty-loving human hearts for whom the scene was made.

Berlin — The Brandenburg Gate — the Emperor passes. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

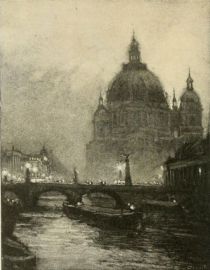

Berlin — Fountain of Neptune, with Royal Stables and Rathaus Tower. Drawn by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — The Old Museum (in the distance), as seen from the base of the Monument to Emperor William I. Drawn by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — The Bridge of the Elector (Kurfürsten-Brücke) over the Spree, with the river-front of the Royal Castle and the Cathedral. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — The Cathedral and the Frederick Bridge, from the Circus Busch on the north side of the Spree. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — The Janowitz Bridge over the Spree. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — Palace of the Reichstag, fronting the Königs Platz. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — The Royal Castle, Charlottenburg, as seen from the Gardens. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — In the Tiergarten. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — Wertheims Store in the Leipziger-Strasse. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — A Glimpse of Old Berlin (Am Krögl). Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

Berlin — The Landwehr Canal with the Potsdam Bridge, as seen from the Konigin-Augusta-Strasse. Painted by Karl O Lynch von Town.

alle Kapitel sehen