I. Danzig.

A Baltic fog rolled in from the north as my train rolled in from the south, bringing an ideal hour for the first impressions of a city so full of Northern melancholy, one so far from the beaten track and so romantic, as Danzig. Down a street full of gargoyles and curious stone platforms there loomed through the mist a monstrous church, crowned with pinnacles and a huge, blunt tower.

A gate that seemed like the facade of an Italian palace pierced by a triumphal arch opened on a street of fascinating old gables, and beyond them rose a Rathaus with an exquisite steeple. I passed between tall, slim palaces, through the arches of a water-gate, and came out by the river, to fill my lungs with a sudden draught of ozone and to realize that I was almost in the presence of the Baltic.

An alcove of the Green Bridge proved the place of places in which to modulate one's soul down from the shrill key of the twentieth century to the deep, mellow tonality of the Middle Ages.

Toward the sea swept an unbroken line of romantic architecture, narrow, sharp-gabled houses intermingled with towered water-gates, and, last of all, the profile of the Krahn Thor, or Crane Gate, Danzig's unique landmark, its stories projecting one beyond another like those of Hildesheim's houses. On the island formed by two arms of the Mottlau the black and white of half-timbered granaries started strongly out of the mist.

The river bristled with romantic shipping; and as I walked the quay, I caught, between gables, the glow of the lights of the Lange Markt flushing the fog into a rosy cloud the center of which was the steeple of the Rathaus. It was as though beauty had been given an aureole.

I turned a corner, and wandered along the other shore of the island, past a deserted waterway and a strange, crumbling tower called the Milk-can Gate, then back again to the Green Bridge. The darkness had thickened so that one could no longer distinguish the separate house-fronts, but all the lamps along the shore had their soft auras of mist, and the surface of the water was one delicate shimmer, with strong columns of light at regular intervals, among which the crimson lantern of a passing boat wrought amazing effects.

Where had I known such an evening before? As memory wandered idly about the harbor of Lübeck, the bridges of Nuremberg, the riversides of Würzburg and Breslau, I was flashed in a trice to the „Siren of sea-cities,“ that

floating film upon the wonder-fraught

Ocean of dreams,

and it came to me with a glow of pleasure that this place had from of old been called „The Venice of the North.“

This, then, was my introduction to Danzig, and I never think of it without seeing streets full of high, narrow facades melting one into another, gently curving streets alive with rich reliefs, statues of blurred worthies, and inquisitive gargoyles, the blunt, mighty Church of St. Mary looming above them like a mountain. I can never see the name of Danzig without beholding a dusky waterway lined with medieval structures and — strange juxtaposition — a jewel of Reformation art with its rosy aureole.

But it is delightful to remember how, on the following morning, the city drew aside her veil and stood revealed in that fresh depth of coloring found only near the misty seas of the North in such places as Lübeck and Wisby, Amsterdam and Bruges.

Danzig is as easy to compass as Dresden, for the most interesting and beautiful buildings have crowded themselves about the Church of St. Mary as though attracted by a crag of lodestone. The ancient moat and the earthen wall must have had a concentrative as well as decorative effect on the city, and one can imagine the inward pressure bending the longest streets into their present graceful curves. A few years ago, alas! these fortifications were destroyed by the highly socialistic process of shoveling the mound into the moat, leaving the High Gate shorn of the walls into which it had been originally set as the principal entrance to Danzig.

Seen from the Hay Market outside, where interesting peasant types swarm among wains of green and golden hay, the High Gate composes inevitably with its taller neighbors, the Torture Chamber and the Stock Tower, or prison. This, like the Langgasser Gate, is more a triumphal arch than a city portal. With its four genially modeled gables, the Torture Chamber recalls the Inquisition, its innocent-sounding name and its outrageous significance, while the Stock Tower compromises between the religious aspiration of a Gothic church and the self-conscious dignity of a Renaissance town hall. The only hint of its real function is supplied by a stone jailer with a ring of keys, who leers from a dormer window at the passer-by with a gesture of welcome. The narrow court below, through which prisoners were led to the red-hot pincers and the rack, is one of the most soothing nooks in Danzig, with its bracketed arcades and harmonious gloom, its riot of old lumber, the myriad tiny roofs that start out from the tower, and its view, framed by three great arches, of the Lang-Gasse.

I did not find the'Langgasser Gate as charming as when its extravagance had been softened by the mist of the previous evening; but the Rathaus steeple was even more glorious in the full morning light, and, seen from three directions, finished the street vista superbly.

A Rathaus interior is not often inspiring, but here were carvings, mosaics, frescos, and furniture of extraordinary beauty, tokens of the Renaissance relationship between North and South. And it was interesting to find in the White Chamber a modern historical fresco of Danzig delegates presenting a painting of their city to the Venetians in 1601. If this old canvas should come to light to-day in some private Italian collection, it would be a very fair portrayal of modern Danzig. For in the room sacred to the burgomaster hangs a „Tribute Money,“ painted in 1601, with the Lange Markt in the background virtually as it appears to-day, a neat refutation of those pessimists who claim that romantic Germany has been „restored“ to death. This room and the Red Chamber rise to the highest levels of the German Renaissance. Between them winds a unique spiral staircase of carved oak.

Separated from the Rathaus by a narrow street and two narrow gables is that most interesting building, the Artushof, or Court of Arthur. This was built by the medieval Teutonic Order of Knights as a patrician club-house, where were kept alive the traditions of King Arthur and his Round Table. It is good to remember how the Arthurian legends penetrated like a sweet savor into these terrible lands, how the Knights built as their Camelot, not many leagues away, the Marienburg, which remains the mightiest of German castles; and how, when Poland and Brandenburg were fighting for the prize of fourteenth-century Danzig, the Knights came to her rescue, and kept her under their protection until she grew strong and beautiful.

Their first thought was to build this Court of King Arthur where, at the sound of a bell, the patricians assembled at the great round table to pledge each other in the famous local beer they called Joppe, and plan for the good of the city while the town pipers made music. Tournaments were sometimes held in the Lange Markt outside. The gentlemen rode in the order of their seating at the round table. The fairest ladies awarded the prizes; and all danced together afterward in the great hall.

To look at the Artushof is to look back through the centuries to the two brightest periods of local history. The three Gothic windows, fit for the clearstory of a cathedral, typify the monumental life of the Teutonic Order when Danzig was building the Rathaus and the Stock Tower, the Crane Gate and the Church of St. Mary; while the portal and the gable tell of the proud adventurers who, under the protection of Poland, were leading spirits in the Hanseatic League, and, while well-nigh the remotest of Germans from the scene of the Italian Renaissance, were yet among the most sensitive to its influence.

The hall itself would have befitted King Arthur and his knights. Four slender shafts branch out into rich vaulting, as though four huge palms had been petrified by the magic of Merlin. The art of the Artushof was intended rather to amuse than to edify, and the decorations seemed like so many glorified toys. Models of the ships of Hansa days hovered in full sail overhead. The hugest and greenest of Nuremberg stoves filled one corner, a piece of pure ornament which had never known the indignity of fire. The paneled walls were filled with curious wooden statues and large paintings. I noticed a painted Diana about to transfix a stag, which started desperately from the wall in high relief. A buck with real hide and antlers hearkened superciliously to the lyre of a painted Orpheus. But the picture that pleased me most was called „The Ship of the Church.“ To my unnautical eye it seemed that the Madonna and two popes were traveling first cabin, a couple of military saints second, while humble old Christopher was thrust away into the steerage, and microscopic laymen were doing all the work.

Arthur's Court has relaxed its ancient rule against „talking shop.“ In fact, it has become the city exchange. Yet the old atmosphere of leisure and sociability still hangs about it. A notice states that ladies are not allowed on the floor during the hour of business. Having spent that hour in Merlin's hall, I am able to declare that if the brokers of New York would only pattern after their Danzig colleagues, their lives would gain in mellowness what they might lose in brilliance. Grain seemed the sole commodity on the market. The round board of the old knights had given place to smaller tables filled with wooden bowls of it. I watched the brokers chatting and dreaming away their little hour, sifting the kernels idly through their fingers in a delicious dolce far niente. Suddenly one group began to buzz with a note of American animation. „Now,“ thought I, „they are getting down to business.“ But as I drew near, I heard the most excited bidder saying something about „the ideality of the actual.“ Suddenly as I stood marveling, and wishing that the author of „The Pit“ had been spared to view that paradoxical scene with me, the enigma was solved in a flash. It was clear that the grain in those curious bowls had never felt the contaminating touch of modern bulls and bears, of thrashing-machines or modern elevators. It had come direct from those

Long fields of barley and of rye

That clothe the wold and meet the sky,

And thro’ the field the road runs by

To many-towered Camelot.

In this atmosphere of medieval romance I moved away, and during my sojourn on the banks of the Vistula I inhaled romance with every breath. For the lure of Danzig is largely the lure of Gothic and Renaissance times; and what is worthier to succeed the spirit of medieval knighthood than the spirit of the age when Europe was born again?

An open portal invited me next door into the hall of a well-preserved patrician dwelling. It was a typical Renaissance interior. There was a frieze of the quaint biblical tiles made in Danzig by refugees from Delft, and the furniture, the brilliant brasses, the sculptured doors and ceiling, and the stairway that wound to a gallery at the farther end, were blended in a harmony of refinement that would have cheapened most palace halls.

I stepped out into the Lange Markt and gazed to my heart's content on the long lines of Renaissance palaces for which Danzig is famous, the styles of North and South standing side by side in friendly rivalry, and testifying to the cosmopolitanism of that great time. In the evening mist along the water-side I had received — or thought I had received — vague impressions of Venice. Now, as I lingered in a day- dream inside the Green Gate, the city still gave forth a delicate aroma of Italy; but the scene was shifted. Perhaps the change was wrought by the suggestion of Lorenzo de Medici's sculptured head looking down from one of the house-fronts. At any rate, as I enjoyed the Lange Markt through halfclosed eyes, the three great arches of Arthur's Court resolved themselves into the Loggia dei Lanzi; the solid, angular body of the Rathaus into the bulk of the Palazzo Vecchio; the fountain of Neptune expanded under my eyes; the same old flock of wheeling pigeons filled the air; and, at a vague glimpse of a blunt and mighty tower looming in the distance, I instinctively murmured the name of Giotto.

In leaving Arthur's Court I had traversed at a step the most significant period of local history. The Teutonic Order, its work being done, fell on evil days, became the „old order,“ and, jealous of the city's growing importance in the Hanseatic League, began to oppress it. Once again the old order yielded place to the new. Danzig cast off the yoke of the Knights, and became the ward of Poland. The people had long been under Dutch influence, and now their contact with the most light-hearted and luxurious of all Slavic races prepared them for the cosmopolitan time when their ships should bear to Venice the grain of the Northeast and bring home in return the glowing spirit of the Italian Renaissance.

Those were days when the wealth, the aristocracy, and the splendor of Danzig were proverbial. The merchant assumed the garments and the manners of princes. In his Northern isolation he decreed his own styles, adopting the ruffs of Italy, the mantles of Spain, and the furs of Russia. A Parisian traveler who happened upon the city in 1635 wrote in astonisliment of the „ladies who walk about in their furs like doctors of the Sorbonne.“ And another complained, a few years later, that „you 'll not leave Danzig with a whole skin if you don't address every sailor and small-sulphur-match-peddler as ‘My Lord.’”

In preserving the spirit of aristocratic town life in the Renaissance, the city has done for North Germany what Nuremberg has done for South Germany. Nuremberg built its houses with greater picturesqueness and variety; Danzig, with greater durability, with more unity of style and grouping; and it has kept out modern discords more successfully.

The townsman ordered his dwelling in the same lordly spirit in which he ordered his clothes. Brick would do for his church, but stone was none too good for his house. And these rich façades are almost as surprising in this stoneless country as façades of silver.

It is interesting to compare the Northern style with the Southern. The Italian tends to horizontal lines, graded orders of pilasters, simplicity and nobility of proportion, a classical feeling for the structural. The Dutch tends to the vertical, is fond of lofty rooms, of sharply peaked gables, of brick walls sown full of unstructural stone ornament. Legend says that the façade of the Steffen House near the Artushof was brought from Italy. It is, at any rate, one of the purest Italian palaces in Germany. And yet it does not quarrel with the Dutch houses near it. The rivalry is friendly, and lends vivacity to the street. It is amusing to see the coalition of North and South that resulted when both styles simultaneously laid hold of the same building, as at Lang-Gasse 37, and in the English House.

Mottos are the rule over the doors, and they are apt to be laconic, like „Als ( AUes) in Got“ or „Glo- ria Deo Soli.“ That is the way the townsmen talk- laconically, earnestly, to the point. Latin is very popular, and the city's motto, „Nec temere nec timide,“ is everywhere. At Töpfer-Gasse 23 are these lines:

Hospes pulsanti tibi se mea janua pandet:

Tu tua pulsanti Pectora pande Deo.

(Guest, to you when you knock this my portal will open: Do you open your heart wide to the summons of God.)

And directly opposite the tower of the Church of St. Mary a pious chisel of 1558 cut this into the wall:

Wir bauen hier grosse Häuser und feste,

Und sind doch fremde Gaeste;

Und wo wir ewig sollen sein,

Da bauen gar wenig ein.

(On palaces we waste our force

Though here we 're only visitors;

But where we shall forever be

Too few build we.)

The streets are so rich to-day because, as a Polish city, Danzig suffered little from the Thirty Years' War, and because it was wise enough to build its houses of fireproof materials. But fireproof materials are not intimate, friendly things, and in few other places do the houses seem so aristocratic and aloof as here. Tall, narrow, richly sculptured, they shoot upward as though despising the democracy of the pavement.

But even as the dwellings of exclusive Augsburg are frescoed into friendliness, here they are saved from utter misanthropy by a unique architectural feature. For in certain dreamy streets about the Church of St. Mary are the remnants of Danzig's famous Beischläge, stone porches as wide as the house and extending far out upon the pavement, to the confusion of modern traffic and to the joy of seekers after the picturesque. The steps are flanked with carved posts or with huge balls of Swedish granite. The balustrades are arabesques of iron, or slabs of stone decorated, like Roman sarcophagi, with mythological reliefs or with scenes from the Old Testament as naive as Delft tiles. Jolly gargoyles still grin from the partition ends in memory of the good old times when every townsman lounged on his own Beischlag, or his neighbor's, in the cool of the day, receiving his tea and his friends. In the Jopen-Gasse the effect of these platforms of irregular height and width is inimitably genial, and the Frauen-Gasse, where they stretch in unbroken lines, undisturbed by the practical modern world, is a little idyl that would be quite impossible to duplicate. The Frauen-Gasse is, no doubt, an absolute novelty to the porchless European, but the American is somehow reminded of old Philadelphia, and how a touch of art might have transfigured the poor little front „stoop“ at home.

In laying out their city, the people developed a truly Latin feeling for composition, and one is constantly delighted with Florentine effects of vista. They thought of their streets as narratives the beginning of which must be interesting, the end, thrilling. Thus the Lang-Gasse begins with a Gothic prison and an elaborate portal, and curves gently about, to end with a tower that is like „the sound of a great Amen.“ Likewise the Lange Markt runs from the rhythmic gables and arches of the Green Gate to the Rathaus; and the picturesque battlements of St. Peter's send the Poggenpfuhl toward the same noble cadence. Even that narrow way known as the Kater-Gasse lies between St. Peter's and the triple front of Holy Trinity, while the Frauen-Gasse leads from a water-gate to the choir of the Church of St. Mary, with its high windows, its pinnacles, and its crenelated gables. But the finest street vista is the view down the Jopen-Gasse.

At the head of the street hes the arsenal, rioting in all the happy excesses of the later Flemish Renaissance. On each side stretch the narrow, aristocratic houses, with their Beischläge; and from among the gables at the end of the street rises the huge, plain façade and tower of the Church of St. Mary. I can never look at that pile, half fortress, half house of God, without imagining the nave full of worshipers ponderously chanting Luther's tremendous hynm, „Ein' feste Burg ist unser Gott.“ It is the most German thing in Danzig. It is even one of the most German things in Germany. For the brick Gothic of the Baltic and of Silesia was evolved so independently of foreign influence that it expresses the national spirit better than any other architecture.

The original inhabitants of this corner of the world were, in all likelihood, the Goths. And it is amusing to imagine their surprise if they could have foreseen that a French style would be named, in misplaced scorn, after them and that their home would, by a freak of chance, become the headquarters of the only really German variety of that style. For a church like St. Mary's is hardly Gothic in the sense that the cathedrals of Cologne and Ratisbon are; but, in the sense that the Goths were Germans, it is, strictly speaking, the only Gothic.

The Church of St. Mary is the largest of all Protestant churches, equaling Notre Dame in area. And it reflects the character of its builders quite as vividly as does the cathedral of Paris. Its castle-like walls bespeak the military instincts of the North German. The huge, plain body and blunt tower symbolize the downrightness, the sturdiness, the honest largeness of a nature whose lack of polish verges on the coarse. The fine proportions tell of his poise. The obvious construction, unobscured by detail, reminds one that this is the clear-headed country of Schopenhauer and of Kant.

Certain traits in this church are specially characteristic of the land of the Teutonic Order, such as a square choir, aisles level with the nave, and star vaulting that reminds one of Arthur's Court and the Marienburg.

Here as everywhere the Baltic architects were little concerned to ornament the interiors of their churches. They left that to the painter, the wood sculptor, the bronze founder, and the artist in wrought-iron. War has been kind to St. Mary's, so that it remains a veritable treasure-house of ecclesiastical furniture. And a dramatic touch is given by one of Napoleon's cannon-balls, which for a century has projected from the vaulting — a single, sinister eye looking greedily down on the multitude of beautiful and fragile things below.

The world is indebted to the cool, unfanatical Danzigers for saving these relics of popery from the destructive storms of the Reformation, and one recalls that Schopenhauer was born almost within the shadow of the old walls and must have had some of his earliest impressions of the beautiful from the paintings and sculptures there.

In no other German church have I found a more engaging group of altarpieces. An added charm came with the feeling that the spectacles of the art professor had been so busy gleaming elsewhere that they had left important things undiscovered here. Special privilege allowed me to enter the Blind Chapel. The pavement was broken, and the guide warned me at every moment not to break through into the graves below. The chapel was well named. It has no windows; but in the dim light I made out on the wings of an altar two paintings of great beauty, at the same time sweet and virile, as though Stephan Lochner and Memling had been fused. The guide murmured vaguely of the school of Kalkar, which I could readily associate with the other four panels. But only a great master could have created that „St. John“ and that „St. Helena.“ Whose hand had done them? For a moment I prayed to be a German art professor, with time and erudition enough and spectacles sufficiently potent to solve that enticing problem.

The next moment my prayer had a perverse answer; for in the chapel of the Rheinhold Fraternity another problem altar came to light. „All Flemish,“ said the guide. And in the tender, delicious humor and sympathy of the wooden reliefs from the life of the Virgin I could feel the hand of Van Wavere. But whenever I gazed at the saints of the outer panels, the thought of a great master persisted. For a layman few things are more futile or more exciting than such speculations. But I am sure that these neglected masterpieces will come into their own when travelers begin to realize that they must not miss Danzig.

The church teems with other interesting altars, and the chief of them is also the chief work of art in the city.

Hans Memling's „Last Judgment“ is well known in reproduction, but speech is like an under-exposed negative when it tries to give the contrast of the Lord's dull scarlet robe with the liquid bronze armor of Michael, who is weighing the sons of men in a pair of scales. Is it a subtle interpretation of Teutonic physical ideals that the short of weight are cast into the flaming pit, while their corpulent brothers are started toward heaven's late-Gothic portal? At any rate, I found Low Country humor in the curtsies of the blessed to that high official St. Peter, their evident reluctance to pose thus in „the altogether,“ and their eagerness to slip into their heavenly robes. This altar was painted in Bruges for a representative of the Medici, and was destined for a Florentine church. It had actually started for Italy in a Burgundian galley when it was captured by a cruiser of Danzig and presented to St. Mary's, where it stayed, despite the threats and wheedlings of Pope Sixtus IV.

The fabulous vies with the beautiful in the atmosphere of this old church. It is said that the maker of the mechanical clock was blinded by the burgomaster, so that he might not make another for the rival city of Lübeck. In a chapel pavement I came upon another myth. Here a child was buried that struck its mother, and died soon after; and the five small holes that I saw in the stone floor were made by the little dead fingers reaching up from the grave for forgiveness. These are good specimens of the gruesomeness of Baltic legends. But the guide told a gentler one in All Saints' Chapel, pointing out a stone that hung by a cord:

„Once upon a time a monk was hurrying home with a loaf of bread. ‘Give me what is under your robe,’ cried a beggar-woman. ‘I starve.’

„‘It is only a stone to throw at the dogs,’ returned the monk. And, sure enough, when he came to look, the loaf had turned to stone. There it hangs.“

Besides its altars and legends St. Mary's Church owns priceless treasures of gold and silver, old ivories and precious stones. It has wonderful reliquaries and manuscripts, Byzantine and Romanesque and Gothic embroideries, and the finest collection of church vestments in Germany. But in money the church is so poor that its beautiful things are fast being ruined for lack of proper attention. It is a worse case of poverty and neglect than that of the notorious cathedral at Worms.

Among the other churches, I preferred St. Peter's, with its picturesque tower; and St. Catharine's, with its interesting pulpit and font and its noble west front. But the best thing about St. Catharine's was a little stream called the Radaune, which ran under its walls. It made an island close at hand, filled with grass and flowers and a Gothic mill, put up five hundred years ago by the Teutonic Order, still grinding, under its vast expanse of tiles, the sort of grain that brokers dream over in the Artushof. It seemed to me the most patriarchal of buildings, and the Napoleonic cannon-ball in its side added to its dignity. The brook, with its flowering island and hoary mill, made a picture that would have seemed unreal in a city less romantic.

I spent a few moments with the woodbined walls, the font-railing, and the perfect vaulting of St. John's, but after the gloom of so many church-interiors, it was good to turn a while from the streets, the tall gables of which conspired to shut out the light.

I struck east through the ancient, double-bastioned Crane Gate, and came out suddenly into the sunshine and vivacious life of the water-front. For the time I had forgotten about Danzig history, but a whistled melody floating up from the river brought it back with a rush. For I realized all at once that the tune was part of a Chopin polonaise, and that this scene had once been for two centuries the port of Poland.

The port of Poland! The words suggested the famous „sea-coast of Bohemia.“ And I began to wonder if this very region were not the nearest mundane approach to Shakspere's enchanted bourne. The fancy came lightly but it seemed worthy a second thought. Shakspere had borrowed the plot and the geography of „A Winter's Tale“ from a novel by Greene, published only nineteen years after Danzig became a part of Poland. The port had long been familiar to English sailors and was beginning then to trade with Sicily, the scene of the story. Now when the romantic fact became known that the Slavic people of Central Europe had at last a seaboard of their own, what would be more natural than for a novelist to use the region as a background, confusing two sister nations that are to this day often confused?

Touched by the glamour of such speculations it is no wonder that the Long Bridge was fascinating, even in the clarity of noon, with only a suspicion of shadow on it. Unlike other bridges, the Long Bridge runs conservatively along the river-bank, content to have its long melody of narrow, peaked gables rhytlimically marked by the massive, recurrent chords of gate-towers. Unamphibious, it keeps the land without aspiring to the granaries on the other shore, which used to hold four million bushels of Polish and Silesian grain in the days before the tariff destroyed the river trade, and the siege of 1813 destroyed the most characteristic of the buildings. Their finest remaining example is the „Gray Goose,“ the noble proportions of which speak of the wealth and taste of former days. The granaries still bear such old names as Golden Pelican, Little Ship, Whale, Milkmaid, and Patriarch Jacob.

Although the old town will never regain the prestige of the time when it was one of the chief commercial centers of the medieval world, yet it does a thriving business to-day in Prussian beet-sugar, English coal, American oil, and Swedish iron. And it is still famous for its liqueurs, one of which inspired the student song „Krambambuli.“ The German navy was born in the shipyards at the mouth of the Mottlau; and of late beautiful old Danzig has been threatening to become a factory town and send her sweetness and romance up in smoke. For she is already manufacturing steel, glass, chemicals, machines, and weapons, and has founded a polytechnic school.

It was good to dismiss such thoughts and step into a rude ferry-boat that showed no symptoms of twen- tieth-century progress. I paid a single pfennig to a boy, who fished a chain from the water, hitched him- self to it, and walked me across to the Bleihof , where waterways lured in four different directions. I grew fond of that ferry, its ragged official, its rough, sim- ple passengers, and fell into the regular habit of being walked to the Bleihof at dusk to watch through a maze of masts and ropes the color fading from the western sky. The belfry of St. John's would darken into one of Rothenburg's matchless wall-towers. One by one the lights of the opposite shore would throw wavering yellow paths across to beckon me back.

A little below the Crane Gate squats an old, round tower called the „Swan,“ which wears a sharp-peaked dunce-cap of red tiles. It is a pathetic reminder of the Teutonic Order's final attempt to keep Danzig German; for when the citizens seized the Crane Gate and fortified it against them, the Knights began this round tower near their castle, saying:

Bauen sie den Krahn,

So bauen wir den Schwan.

(And if they build the Crane,

Why, we shall build the Swan.)

The castle vanished with the order, and the Swan to-day is smothered breast-high in small houses, the smallest of which testifies to the cosmopolitanism of its tarry guests by the sign „Stadt London“

Near the Fish Market, where the little Radaune rushes with a loud noise into the Mottlau, the quay has been prettily christened „Am Brausenden Wasser“ („By the Roaring Water“) . This is the favorite haunt of longshoremen, sailors, and the famous Danzig sackcarriers, herculean figures with their wide blue pantaloons and their swathed calves. And beside the quay belongs a flotilla of dusky fishingboats, draped with many-colored sail-awnings and with funnel-shaped nets that hang drying from the tips of the masts.

Before parting from a city to which I have grown attached, I like to stand on one of its high places and see in one. sweeping glance what it is that I am leaving. It is like gripping a friend's hand and looking him square in the eye.

Toil and twenty-five pfennigs was the price of climbing the tower of the Church of St. Mary, and I grew grateful that it had remained blunt and sturdy like its people. But I should have been willing to toil on indefinitely; for I had seen splendid sights from the steeples of Ulm and Munich, of Mayence and Strassburg, but never in Germany a panorama to equal this.

A little to the south the exquisite Rathaus steeple was a fellow-aspirant, and one could almost make out the gilt features of its royal weathercock — Sigismund of Poland— as the wind twirled him about, and count the false jewels in his crown. Beneath rose the pinnacled back of the Artushof and the fine façades of the Lange Markt, where I had dreamed of Florence; beyond them a long line of granaries gave proof of the hidden Mottlau. Farther away, over a sea of fantastic roofs, was St. Peter's crenelated tower, and beyond it the fields flowed on to the distant spire of St. Albert's and rolled upward in gentle undulations to a ridge that swung westward, a background for the picturesque Stock Tower.

Everywhere was a crowd of entrancing old gables interspersed with the dusky red of well-weathered tiles. Northward was spread a ruddy expanse of church roofs, and behind them swung in noble curves the final reaches of the Vistula, fresh from the lands of Krakow and Warsaw; while beyond the pinnacles of the Church of St. Mary itself and the tranquil streets in its shadow, curving past romantic gatetowers and the woodbined walls of St. John's, the Mottlau wound to join the Vistula and seek the ocean, whose breakers dashed a league away, a mighty gulf of grayish blue, flecked by one immaculate sail.

A gate that seemed like the facade of an Italian palace pierced by a triumphal arch opened on a street of fascinating old gables, and beyond them rose a Rathaus with an exquisite steeple. I passed between tall, slim palaces, through the arches of a water-gate, and came out by the river, to fill my lungs with a sudden draught of ozone and to realize that I was almost in the presence of the Baltic.

An alcove of the Green Bridge proved the place of places in which to modulate one's soul down from the shrill key of the twentieth century to the deep, mellow tonality of the Middle Ages.

Toward the sea swept an unbroken line of romantic architecture, narrow, sharp-gabled houses intermingled with towered water-gates, and, last of all, the profile of the Krahn Thor, or Crane Gate, Danzig's unique landmark, its stories projecting one beyond another like those of Hildesheim's houses. On the island formed by two arms of the Mottlau the black and white of half-timbered granaries started strongly out of the mist.

The river bristled with romantic shipping; and as I walked the quay, I caught, between gables, the glow of the lights of the Lange Markt flushing the fog into a rosy cloud the center of which was the steeple of the Rathaus. It was as though beauty had been given an aureole.

I turned a corner, and wandered along the other shore of the island, past a deserted waterway and a strange, crumbling tower called the Milk-can Gate, then back again to the Green Bridge. The darkness had thickened so that one could no longer distinguish the separate house-fronts, but all the lamps along the shore had their soft auras of mist, and the surface of the water was one delicate shimmer, with strong columns of light at regular intervals, among which the crimson lantern of a passing boat wrought amazing effects.

Where had I known such an evening before? As memory wandered idly about the harbor of Lübeck, the bridges of Nuremberg, the riversides of Würzburg and Breslau, I was flashed in a trice to the „Siren of sea-cities,“ that

floating film upon the wonder-fraught

Ocean of dreams,

and it came to me with a glow of pleasure that this place had from of old been called „The Venice of the North.“

This, then, was my introduction to Danzig, and I never think of it without seeing streets full of high, narrow facades melting one into another, gently curving streets alive with rich reliefs, statues of blurred worthies, and inquisitive gargoyles, the blunt, mighty Church of St. Mary looming above them like a mountain. I can never see the name of Danzig without beholding a dusky waterway lined with medieval structures and — strange juxtaposition — a jewel of Reformation art with its rosy aureole.

But it is delightful to remember how, on the following morning, the city drew aside her veil and stood revealed in that fresh depth of coloring found only near the misty seas of the North in such places as Lübeck and Wisby, Amsterdam and Bruges.

Danzig is as easy to compass as Dresden, for the most interesting and beautiful buildings have crowded themselves about the Church of St. Mary as though attracted by a crag of lodestone. The ancient moat and the earthen wall must have had a concentrative as well as decorative effect on the city, and one can imagine the inward pressure bending the longest streets into their present graceful curves. A few years ago, alas! these fortifications were destroyed by the highly socialistic process of shoveling the mound into the moat, leaving the High Gate shorn of the walls into which it had been originally set as the principal entrance to Danzig.

Seen from the Hay Market outside, where interesting peasant types swarm among wains of green and golden hay, the High Gate composes inevitably with its taller neighbors, the Torture Chamber and the Stock Tower, or prison. This, like the Langgasser Gate, is more a triumphal arch than a city portal. With its four genially modeled gables, the Torture Chamber recalls the Inquisition, its innocent-sounding name and its outrageous significance, while the Stock Tower compromises between the religious aspiration of a Gothic church and the self-conscious dignity of a Renaissance town hall. The only hint of its real function is supplied by a stone jailer with a ring of keys, who leers from a dormer window at the passer-by with a gesture of welcome. The narrow court below, through which prisoners were led to the red-hot pincers and the rack, is one of the most soothing nooks in Danzig, with its bracketed arcades and harmonious gloom, its riot of old lumber, the myriad tiny roofs that start out from the tower, and its view, framed by three great arches, of the Lang-Gasse.

I did not find the'Langgasser Gate as charming as when its extravagance had been softened by the mist of the previous evening; but the Rathaus steeple was even more glorious in the full morning light, and, seen from three directions, finished the street vista superbly.

A Rathaus interior is not often inspiring, but here were carvings, mosaics, frescos, and furniture of extraordinary beauty, tokens of the Renaissance relationship between North and South. And it was interesting to find in the White Chamber a modern historical fresco of Danzig delegates presenting a painting of their city to the Venetians in 1601. If this old canvas should come to light to-day in some private Italian collection, it would be a very fair portrayal of modern Danzig. For in the room sacred to the burgomaster hangs a „Tribute Money,“ painted in 1601, with the Lange Markt in the background virtually as it appears to-day, a neat refutation of those pessimists who claim that romantic Germany has been „restored“ to death. This room and the Red Chamber rise to the highest levels of the German Renaissance. Between them winds a unique spiral staircase of carved oak.

Separated from the Rathaus by a narrow street and two narrow gables is that most interesting building, the Artushof, or Court of Arthur. This was built by the medieval Teutonic Order of Knights as a patrician club-house, where were kept alive the traditions of King Arthur and his Round Table. It is good to remember how the Arthurian legends penetrated like a sweet savor into these terrible lands, how the Knights built as their Camelot, not many leagues away, the Marienburg, which remains the mightiest of German castles; and how, when Poland and Brandenburg were fighting for the prize of fourteenth-century Danzig, the Knights came to her rescue, and kept her under their protection until she grew strong and beautiful.

Their first thought was to build this Court of King Arthur where, at the sound of a bell, the patricians assembled at the great round table to pledge each other in the famous local beer they called Joppe, and plan for the good of the city while the town pipers made music. Tournaments were sometimes held in the Lange Markt outside. The gentlemen rode in the order of their seating at the round table. The fairest ladies awarded the prizes; and all danced together afterward in the great hall.

To look at the Artushof is to look back through the centuries to the two brightest periods of local history. The three Gothic windows, fit for the clearstory of a cathedral, typify the monumental life of the Teutonic Order when Danzig was building the Rathaus and the Stock Tower, the Crane Gate and the Church of St. Mary; while the portal and the gable tell of the proud adventurers who, under the protection of Poland, were leading spirits in the Hanseatic League, and, while well-nigh the remotest of Germans from the scene of the Italian Renaissance, were yet among the most sensitive to its influence.

The hall itself would have befitted King Arthur and his knights. Four slender shafts branch out into rich vaulting, as though four huge palms had been petrified by the magic of Merlin. The art of the Artushof was intended rather to amuse than to edify, and the decorations seemed like so many glorified toys. Models of the ships of Hansa days hovered in full sail overhead. The hugest and greenest of Nuremberg stoves filled one corner, a piece of pure ornament which had never known the indignity of fire. The paneled walls were filled with curious wooden statues and large paintings. I noticed a painted Diana about to transfix a stag, which started desperately from the wall in high relief. A buck with real hide and antlers hearkened superciliously to the lyre of a painted Orpheus. But the picture that pleased me most was called „The Ship of the Church.“ To my unnautical eye it seemed that the Madonna and two popes were traveling first cabin, a couple of military saints second, while humble old Christopher was thrust away into the steerage, and microscopic laymen were doing all the work.

Arthur's Court has relaxed its ancient rule against „talking shop.“ In fact, it has become the city exchange. Yet the old atmosphere of leisure and sociability still hangs about it. A notice states that ladies are not allowed on the floor during the hour of business. Having spent that hour in Merlin's hall, I am able to declare that if the brokers of New York would only pattern after their Danzig colleagues, their lives would gain in mellowness what they might lose in brilliance. Grain seemed the sole commodity on the market. The round board of the old knights had given place to smaller tables filled with wooden bowls of it. I watched the brokers chatting and dreaming away their little hour, sifting the kernels idly through their fingers in a delicious dolce far niente. Suddenly one group began to buzz with a note of American animation. „Now,“ thought I, „they are getting down to business.“ But as I drew near, I heard the most excited bidder saying something about „the ideality of the actual.“ Suddenly as I stood marveling, and wishing that the author of „The Pit“ had been spared to view that paradoxical scene with me, the enigma was solved in a flash. It was clear that the grain in those curious bowls had never felt the contaminating touch of modern bulls and bears, of thrashing-machines or modern elevators. It had come direct from those

Long fields of barley and of rye

That clothe the wold and meet the sky,

And thro’ the field the road runs by

To many-towered Camelot.

In this atmosphere of medieval romance I moved away, and during my sojourn on the banks of the Vistula I inhaled romance with every breath. For the lure of Danzig is largely the lure of Gothic and Renaissance times; and what is worthier to succeed the spirit of medieval knighthood than the spirit of the age when Europe was born again?

An open portal invited me next door into the hall of a well-preserved patrician dwelling. It was a typical Renaissance interior. There was a frieze of the quaint biblical tiles made in Danzig by refugees from Delft, and the furniture, the brilliant brasses, the sculptured doors and ceiling, and the stairway that wound to a gallery at the farther end, were blended in a harmony of refinement that would have cheapened most palace halls.

I stepped out into the Lange Markt and gazed to my heart's content on the long lines of Renaissance palaces for which Danzig is famous, the styles of North and South standing side by side in friendly rivalry, and testifying to the cosmopolitanism of that great time. In the evening mist along the water-side I had received — or thought I had received — vague impressions of Venice. Now, as I lingered in a day- dream inside the Green Gate, the city still gave forth a delicate aroma of Italy; but the scene was shifted. Perhaps the change was wrought by the suggestion of Lorenzo de Medici's sculptured head looking down from one of the house-fronts. At any rate, as I enjoyed the Lange Markt through halfclosed eyes, the three great arches of Arthur's Court resolved themselves into the Loggia dei Lanzi; the solid, angular body of the Rathaus into the bulk of the Palazzo Vecchio; the fountain of Neptune expanded under my eyes; the same old flock of wheeling pigeons filled the air; and, at a vague glimpse of a blunt and mighty tower looming in the distance, I instinctively murmured the name of Giotto.

In leaving Arthur's Court I had traversed at a step the most significant period of local history. The Teutonic Order, its work being done, fell on evil days, became the „old order,“ and, jealous of the city's growing importance in the Hanseatic League, began to oppress it. Once again the old order yielded place to the new. Danzig cast off the yoke of the Knights, and became the ward of Poland. The people had long been under Dutch influence, and now their contact with the most light-hearted and luxurious of all Slavic races prepared them for the cosmopolitan time when their ships should bear to Venice the grain of the Northeast and bring home in return the glowing spirit of the Italian Renaissance.

Those were days when the wealth, the aristocracy, and the splendor of Danzig were proverbial. The merchant assumed the garments and the manners of princes. In his Northern isolation he decreed his own styles, adopting the ruffs of Italy, the mantles of Spain, and the furs of Russia. A Parisian traveler who happened upon the city in 1635 wrote in astonisliment of the „ladies who walk about in their furs like doctors of the Sorbonne.“ And another complained, a few years later, that „you 'll not leave Danzig with a whole skin if you don't address every sailor and small-sulphur-match-peddler as ‘My Lord.’”

In preserving the spirit of aristocratic town life in the Renaissance, the city has done for North Germany what Nuremberg has done for South Germany. Nuremberg built its houses with greater picturesqueness and variety; Danzig, with greater durability, with more unity of style and grouping; and it has kept out modern discords more successfully.

The townsman ordered his dwelling in the same lordly spirit in which he ordered his clothes. Brick would do for his church, but stone was none too good for his house. And these rich façades are almost as surprising in this stoneless country as façades of silver.

It is interesting to compare the Northern style with the Southern. The Italian tends to horizontal lines, graded orders of pilasters, simplicity and nobility of proportion, a classical feeling for the structural. The Dutch tends to the vertical, is fond of lofty rooms, of sharply peaked gables, of brick walls sown full of unstructural stone ornament. Legend says that the façade of the Steffen House near the Artushof was brought from Italy. It is, at any rate, one of the purest Italian palaces in Germany. And yet it does not quarrel with the Dutch houses near it. The rivalry is friendly, and lends vivacity to the street. It is amusing to see the coalition of North and South that resulted when both styles simultaneously laid hold of the same building, as at Lang-Gasse 37, and in the English House.

Mottos are the rule over the doors, and they are apt to be laconic, like „Als ( AUes) in Got“ or „Glo- ria Deo Soli.“ That is the way the townsmen talk- laconically, earnestly, to the point. Latin is very popular, and the city's motto, „Nec temere nec timide,“ is everywhere. At Töpfer-Gasse 23 are these lines:

Hospes pulsanti tibi se mea janua pandet:

Tu tua pulsanti Pectora pande Deo.

(Guest, to you when you knock this my portal will open: Do you open your heart wide to the summons of God.)

And directly opposite the tower of the Church of St. Mary a pious chisel of 1558 cut this into the wall:

Wir bauen hier grosse Häuser und feste,

Und sind doch fremde Gaeste;

Und wo wir ewig sollen sein,

Da bauen gar wenig ein.

(On palaces we waste our force

Though here we 're only visitors;

But where we shall forever be

Too few build we.)

The streets are so rich to-day because, as a Polish city, Danzig suffered little from the Thirty Years' War, and because it was wise enough to build its houses of fireproof materials. But fireproof materials are not intimate, friendly things, and in few other places do the houses seem so aristocratic and aloof as here. Tall, narrow, richly sculptured, they shoot upward as though despising the democracy of the pavement.

But even as the dwellings of exclusive Augsburg are frescoed into friendliness, here they are saved from utter misanthropy by a unique architectural feature. For in certain dreamy streets about the Church of St. Mary are the remnants of Danzig's famous Beischläge, stone porches as wide as the house and extending far out upon the pavement, to the confusion of modern traffic and to the joy of seekers after the picturesque. The steps are flanked with carved posts or with huge balls of Swedish granite. The balustrades are arabesques of iron, or slabs of stone decorated, like Roman sarcophagi, with mythological reliefs or with scenes from the Old Testament as naive as Delft tiles. Jolly gargoyles still grin from the partition ends in memory of the good old times when every townsman lounged on his own Beischlag, or his neighbor's, in the cool of the day, receiving his tea and his friends. In the Jopen-Gasse the effect of these platforms of irregular height and width is inimitably genial, and the Frauen-Gasse, where they stretch in unbroken lines, undisturbed by the practical modern world, is a little idyl that would be quite impossible to duplicate. The Frauen-Gasse is, no doubt, an absolute novelty to the porchless European, but the American is somehow reminded of old Philadelphia, and how a touch of art might have transfigured the poor little front „stoop“ at home.

In laying out their city, the people developed a truly Latin feeling for composition, and one is constantly delighted with Florentine effects of vista. They thought of their streets as narratives the beginning of which must be interesting, the end, thrilling. Thus the Lang-Gasse begins with a Gothic prison and an elaborate portal, and curves gently about, to end with a tower that is like „the sound of a great Amen.“ Likewise the Lange Markt runs from the rhythmic gables and arches of the Green Gate to the Rathaus; and the picturesque battlements of St. Peter's send the Poggenpfuhl toward the same noble cadence. Even that narrow way known as the Kater-Gasse lies between St. Peter's and the triple front of Holy Trinity, while the Frauen-Gasse leads from a water-gate to the choir of the Church of St. Mary, with its high windows, its pinnacles, and its crenelated gables. But the finest street vista is the view down the Jopen-Gasse.

At the head of the street hes the arsenal, rioting in all the happy excesses of the later Flemish Renaissance. On each side stretch the narrow, aristocratic houses, with their Beischläge; and from among the gables at the end of the street rises the huge, plain façade and tower of the Church of St. Mary. I can never look at that pile, half fortress, half house of God, without imagining the nave full of worshipers ponderously chanting Luther's tremendous hynm, „Ein' feste Burg ist unser Gott.“ It is the most German thing in Danzig. It is even one of the most German things in Germany. For the brick Gothic of the Baltic and of Silesia was evolved so independently of foreign influence that it expresses the national spirit better than any other architecture.

The original inhabitants of this corner of the world were, in all likelihood, the Goths. And it is amusing to imagine their surprise if they could have foreseen that a French style would be named, in misplaced scorn, after them and that their home would, by a freak of chance, become the headquarters of the only really German variety of that style. For a church like St. Mary's is hardly Gothic in the sense that the cathedrals of Cologne and Ratisbon are; but, in the sense that the Goths were Germans, it is, strictly speaking, the only Gothic.

The Church of St. Mary is the largest of all Protestant churches, equaling Notre Dame in area. And it reflects the character of its builders quite as vividly as does the cathedral of Paris. Its castle-like walls bespeak the military instincts of the North German. The huge, plain body and blunt tower symbolize the downrightness, the sturdiness, the honest largeness of a nature whose lack of polish verges on the coarse. The fine proportions tell of his poise. The obvious construction, unobscured by detail, reminds one that this is the clear-headed country of Schopenhauer and of Kant.

Certain traits in this church are specially characteristic of the land of the Teutonic Order, such as a square choir, aisles level with the nave, and star vaulting that reminds one of Arthur's Court and the Marienburg.

Here as everywhere the Baltic architects were little concerned to ornament the interiors of their churches. They left that to the painter, the wood sculptor, the bronze founder, and the artist in wrought-iron. War has been kind to St. Mary's, so that it remains a veritable treasure-house of ecclesiastical furniture. And a dramatic touch is given by one of Napoleon's cannon-balls, which for a century has projected from the vaulting — a single, sinister eye looking greedily down on the multitude of beautiful and fragile things below.

The world is indebted to the cool, unfanatical Danzigers for saving these relics of popery from the destructive storms of the Reformation, and one recalls that Schopenhauer was born almost within the shadow of the old walls and must have had some of his earliest impressions of the beautiful from the paintings and sculptures there.

In no other German church have I found a more engaging group of altarpieces. An added charm came with the feeling that the spectacles of the art professor had been so busy gleaming elsewhere that they had left important things undiscovered here. Special privilege allowed me to enter the Blind Chapel. The pavement was broken, and the guide warned me at every moment not to break through into the graves below. The chapel was well named. It has no windows; but in the dim light I made out on the wings of an altar two paintings of great beauty, at the same time sweet and virile, as though Stephan Lochner and Memling had been fused. The guide murmured vaguely of the school of Kalkar, which I could readily associate with the other four panels. But only a great master could have created that „St. John“ and that „St. Helena.“ Whose hand had done them? For a moment I prayed to be a German art professor, with time and erudition enough and spectacles sufficiently potent to solve that enticing problem.

The next moment my prayer had a perverse answer; for in the chapel of the Rheinhold Fraternity another problem altar came to light. „All Flemish,“ said the guide. And in the tender, delicious humor and sympathy of the wooden reliefs from the life of the Virgin I could feel the hand of Van Wavere. But whenever I gazed at the saints of the outer panels, the thought of a great master persisted. For a layman few things are more futile or more exciting than such speculations. But I am sure that these neglected masterpieces will come into their own when travelers begin to realize that they must not miss Danzig.

The church teems with other interesting altars, and the chief of them is also the chief work of art in the city.

Hans Memling's „Last Judgment“ is well known in reproduction, but speech is like an under-exposed negative when it tries to give the contrast of the Lord's dull scarlet robe with the liquid bronze armor of Michael, who is weighing the sons of men in a pair of scales. Is it a subtle interpretation of Teutonic physical ideals that the short of weight are cast into the flaming pit, while their corpulent brothers are started toward heaven's late-Gothic portal? At any rate, I found Low Country humor in the curtsies of the blessed to that high official St. Peter, their evident reluctance to pose thus in „the altogether,“ and their eagerness to slip into their heavenly robes. This altar was painted in Bruges for a representative of the Medici, and was destined for a Florentine church. It had actually started for Italy in a Burgundian galley when it was captured by a cruiser of Danzig and presented to St. Mary's, where it stayed, despite the threats and wheedlings of Pope Sixtus IV.

The fabulous vies with the beautiful in the atmosphere of this old church. It is said that the maker of the mechanical clock was blinded by the burgomaster, so that he might not make another for the rival city of Lübeck. In a chapel pavement I came upon another myth. Here a child was buried that struck its mother, and died soon after; and the five small holes that I saw in the stone floor were made by the little dead fingers reaching up from the grave for forgiveness. These are good specimens of the gruesomeness of Baltic legends. But the guide told a gentler one in All Saints' Chapel, pointing out a stone that hung by a cord:

„Once upon a time a monk was hurrying home with a loaf of bread. ‘Give me what is under your robe,’ cried a beggar-woman. ‘I starve.’

„‘It is only a stone to throw at the dogs,’ returned the monk. And, sure enough, when he came to look, the loaf had turned to stone. There it hangs.“

Besides its altars and legends St. Mary's Church owns priceless treasures of gold and silver, old ivories and precious stones. It has wonderful reliquaries and manuscripts, Byzantine and Romanesque and Gothic embroideries, and the finest collection of church vestments in Germany. But in money the church is so poor that its beautiful things are fast being ruined for lack of proper attention. It is a worse case of poverty and neglect than that of the notorious cathedral at Worms.

Among the other churches, I preferred St. Peter's, with its picturesque tower; and St. Catharine's, with its interesting pulpit and font and its noble west front. But the best thing about St. Catharine's was a little stream called the Radaune, which ran under its walls. It made an island close at hand, filled with grass and flowers and a Gothic mill, put up five hundred years ago by the Teutonic Order, still grinding, under its vast expanse of tiles, the sort of grain that brokers dream over in the Artushof. It seemed to me the most patriarchal of buildings, and the Napoleonic cannon-ball in its side added to its dignity. The brook, with its flowering island and hoary mill, made a picture that would have seemed unreal in a city less romantic.

I spent a few moments with the woodbined walls, the font-railing, and the perfect vaulting of St. John's, but after the gloom of so many church-interiors, it was good to turn a while from the streets, the tall gables of which conspired to shut out the light.

I struck east through the ancient, double-bastioned Crane Gate, and came out suddenly into the sunshine and vivacious life of the water-front. For the time I had forgotten about Danzig history, but a whistled melody floating up from the river brought it back with a rush. For I realized all at once that the tune was part of a Chopin polonaise, and that this scene had once been for two centuries the port of Poland.

The port of Poland! The words suggested the famous „sea-coast of Bohemia.“ And I began to wonder if this very region were not the nearest mundane approach to Shakspere's enchanted bourne. The fancy came lightly but it seemed worthy a second thought. Shakspere had borrowed the plot and the geography of „A Winter's Tale“ from a novel by Greene, published only nineteen years after Danzig became a part of Poland. The port had long been familiar to English sailors and was beginning then to trade with Sicily, the scene of the story. Now when the romantic fact became known that the Slavic people of Central Europe had at last a seaboard of their own, what would be more natural than for a novelist to use the region as a background, confusing two sister nations that are to this day often confused?

Touched by the glamour of such speculations it is no wonder that the Long Bridge was fascinating, even in the clarity of noon, with only a suspicion of shadow on it. Unlike other bridges, the Long Bridge runs conservatively along the river-bank, content to have its long melody of narrow, peaked gables rhytlimically marked by the massive, recurrent chords of gate-towers. Unamphibious, it keeps the land without aspiring to the granaries on the other shore, which used to hold four million bushels of Polish and Silesian grain in the days before the tariff destroyed the river trade, and the siege of 1813 destroyed the most characteristic of the buildings. Their finest remaining example is the „Gray Goose,“ the noble proportions of which speak of the wealth and taste of former days. The granaries still bear such old names as Golden Pelican, Little Ship, Whale, Milkmaid, and Patriarch Jacob.

Although the old town will never regain the prestige of the time when it was one of the chief commercial centers of the medieval world, yet it does a thriving business to-day in Prussian beet-sugar, English coal, American oil, and Swedish iron. And it is still famous for its liqueurs, one of which inspired the student song „Krambambuli.“ The German navy was born in the shipyards at the mouth of the Mottlau; and of late beautiful old Danzig has been threatening to become a factory town and send her sweetness and romance up in smoke. For she is already manufacturing steel, glass, chemicals, machines, and weapons, and has founded a polytechnic school.

It was good to dismiss such thoughts and step into a rude ferry-boat that showed no symptoms of twen- tieth-century progress. I paid a single pfennig to a boy, who fished a chain from the water, hitched him- self to it, and walked me across to the Bleihof , where waterways lured in four different directions. I grew fond of that ferry, its ragged official, its rough, sim- ple passengers, and fell into the regular habit of being walked to the Bleihof at dusk to watch through a maze of masts and ropes the color fading from the western sky. The belfry of St. John's would darken into one of Rothenburg's matchless wall-towers. One by one the lights of the opposite shore would throw wavering yellow paths across to beckon me back.

A little below the Crane Gate squats an old, round tower called the „Swan,“ which wears a sharp-peaked dunce-cap of red tiles. It is a pathetic reminder of the Teutonic Order's final attempt to keep Danzig German; for when the citizens seized the Crane Gate and fortified it against them, the Knights began this round tower near their castle, saying:

Bauen sie den Krahn,

So bauen wir den Schwan.

(And if they build the Crane,

Why, we shall build the Swan.)

The castle vanished with the order, and the Swan to-day is smothered breast-high in small houses, the smallest of which testifies to the cosmopolitanism of its tarry guests by the sign „Stadt London“

Near the Fish Market, where the little Radaune rushes with a loud noise into the Mottlau, the quay has been prettily christened „Am Brausenden Wasser“ („By the Roaring Water“) . This is the favorite haunt of longshoremen, sailors, and the famous Danzig sackcarriers, herculean figures with their wide blue pantaloons and their swathed calves. And beside the quay belongs a flotilla of dusky fishingboats, draped with many-colored sail-awnings and with funnel-shaped nets that hang drying from the tips of the masts.

Before parting from a city to which I have grown attached, I like to stand on one of its high places and see in one. sweeping glance what it is that I am leaving. It is like gripping a friend's hand and looking him square in the eye.

Toil and twenty-five pfennigs was the price of climbing the tower of the Church of St. Mary, and I grew grateful that it had remained blunt and sturdy like its people. But I should have been willing to toil on indefinitely; for I had seen splendid sights from the steeples of Ulm and Munich, of Mayence and Strassburg, but never in Germany a panorama to equal this.

A little to the south the exquisite Rathaus steeple was a fellow-aspirant, and one could almost make out the gilt features of its royal weathercock — Sigismund of Poland— as the wind twirled him about, and count the false jewels in his crown. Beneath rose the pinnacled back of the Artushof and the fine façades of the Lange Markt, where I had dreamed of Florence; beyond them a long line of granaries gave proof of the hidden Mottlau. Farther away, over a sea of fantastic roofs, was St. Peter's crenelated tower, and beyond it the fields flowed on to the distant spire of St. Albert's and rolled upward in gentle undulations to a ridge that swung westward, a background for the picturesque Stock Tower.

Everywhere was a crowd of entrancing old gables interspersed with the dusky red of well-weathered tiles. Northward was spread a ruddy expanse of church roofs, and behind them swung in noble curves the final reaches of the Vistula, fresh from the lands of Krakow and Warsaw; while beyond the pinnacles of the Church of St. Mary itself and the tranquil streets in its shadow, curving past romantic gatetowers and the woodbined walls of St. John's, the Mottlau wound to join the Vistula and seek the ocean, whose breakers dashed a league away, a mighty gulf of grayish blue, flecked by one immaculate sail.

Dieses Kapitel ist Teil des Buches Romantic Germany

Danzig — Jopen Street and St. Marys Church. Frontispiece Painted by Alfred Scherres.

Danzig — The Crane Gate. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

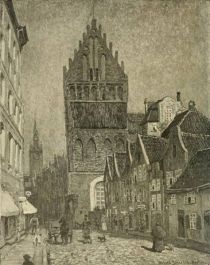

Danzig — The Stock Tower. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

Danzig — The Poggenpfuhl, with St. Peters Church and the Rathaus Tower. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

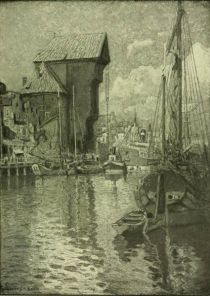

Danzig — The Mottlau and St. Johns Church (Winter Evening). Painted by Alfred Scherres

Danzig — The Fish Market and „The Swan“. Painted by Alfred Scherres.

alle Kapitel sehen