PETROGRAD PAST AND PRESENT

WITH THIRTY ILLUSTRATIONS

Autor: Steveni, William Barnes (1859-?) Journalist und Schriftsteller, Erscheinungsjahr: 1916

Themenbereiche

Enthaltene Themen: Petrograd, Cronstadt, Kronstadt, Memories, Russia, Peter and Paul, Cathedral, Peter the Great

CONTENTS

I. ARRIVAL IN PETROGRAD AND THE NECESSITY FOR PASSPORTS

II. CRONSTADT, THE KEY OF PETROGRAD, AND SOME MEMORIES

III. A ZEALOT OF CRONSTADT

IV. SOME CRONSTADT CHARACTERS

V. THE FOUNDING OF PETROGRAD

VI. THE YOUTH AND GROWTH OF PETROGRAD, WITH SOME HISTORICAL NOTES

VII. THE RIVER NEVA AND THE GREAT FLOODS

VIII. THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1777; THE DEATH OF PRINCESS TAUAKANOFFVA

IX. PETROGRAD DURING THE UEIGN OF ITS FOUNDER; AND AN ACCOUNT OF PETER'S COURT AS SEEN BY PRINCESS WILHELMINA OF PRUSSIA

X. STATUES AND MONUMENTS, HISTORICAL MEMORIES AND SOME SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE CAPITAL

XI. A TRIP UP THE NEVA

XII. THE FORTRESS OF PETER AND PAUL

XIII. THE MODERN CITY AND THE PEOPLE

XIV. THE POLICE OF PETROGRAD

XV. OFFICIALDOM IN RUSSIA

XVI. THE MOUJIKS AND WORKING CLASSES

XVII. THE TSAR, HIS HOUSEHOLD AND HIS LABOURS

XVIII. HOTELS AND RESTAURANTS

XIX. THEATRES, CONCERTS AND PLEASURE GARDENS

XX. CONCERNING THE BALLET

XXI. THE HERMITAGE AND ITS MEMORIES CATHERINE'S FAVOURITE RETREAT

XXII. THE ANITCHKOFF PALACE AND A NARROW ESCAPE

XXIII. THE TAURIDA PALACE AND THE WINTER PALACE

XXIV. THE ALEXANDER NEVSKY MONASTERY

XXV. THE KAZAN CATHEDRAL, THE RIOTS, AND ST ISAAC'S CATHEDRAL

XXVI. TWO TSARS : PAUL, THE "MAD TSAR"; NICHOLAS I., HIS CHARACTER AND AMBITION

XXVII. SIR ROBERT MORIER AND THE BRITISH EMBASSY

XXVIII. COUNT SERGIUS DE WITTE

XXIX. THE RUSSIAN PRESS

XXX. FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS AND THE CENSORS

XXXI. THE BRITISH COLONY — ITS HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

XXXII. KRASNOE SELO AND THE MILITARY MANEUVRES

XXXIII. ALEXANDER III., HIS "MUSEUM," AND THE LATE GRAND DUKE CONSTANTINE

XXXIV. THE ENVIRONS OF THE CITY

THE GRAND DUKE MICHAEL, THE TSAR'S BROTHER, AT THE FRONT

A NOTE ON THE GROWTH OF THE RUSSIAN EMIMUE SINCE THE DAYS OF PETER THE GREAT

SOME AUTHORITIES REFERRED TO FOR THE PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK

INDEX

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

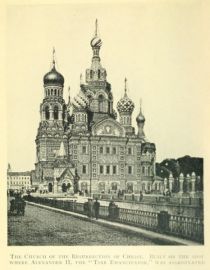

01. The Church of the Resurrection of Christ

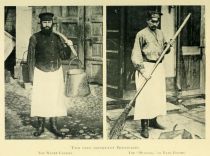

02. Two very Important Personages

03. The Steamer Yermak breaking its way through the Ice

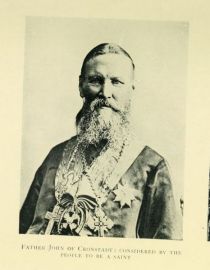

04. Father John of Cronstadt

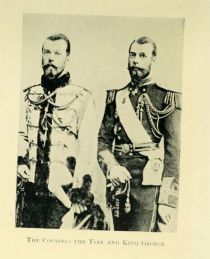

05. The Cousins: the Tsar and King George

06. Building Ships for Russia's Commercial Marine in the Days of Peter the Great

07. Petrograd in the Days of Catherine II.

08. The deep and rapid Neva, with View of the Nicholai Bridge

09. A Crowd on the Nevsky Prospect: "Praznek"

10. The Catherine Canal

11. The Last Days of the beautiful Princess Tarakanoffva in the Fortress

12. A Masquerade in the Days of Peter the Great (1722)

13. The old Winter Palace

14. The Admiralty with its Gilded Spire

15. The Fortress Church of SS. Peter and Paul

16. Russian Railway Guard

17. Typical Russian Coachman

18. A typical Russian Moujik in the Rough State

19. Russian Peasant begging for Alms for the Village Church

20. The Facade of the Imperial Hermitage

21. „Babooshka" Ekaterina II.

22. The Mechailoff Palace, now converted into the Museum of Alexander III.

23. The Anitchkoff Palace on the Nevsky

24. The Kazan Cathedral

25. The Gosteny Dvor (Guest Bazaar) on the Nevsky

26. The Cathedral of St Isaac of Dalmatia

27. The old Mechailoff Palace

28. Russian Standard Bearers of the Guards

29. The Tsar Alexander III.— called the "Peace-lover"

30. The Palace and wonderful Fountains of Peterhoff

I. THE ARRIVAL IN PETROGRAD AND THE NECESSITY FOR PASSPORTS

It was a lovely morning in May when our diminutive steamer the Viking first entered the swift stream of the Neva, by which river the confined and pentup waters of Lake Ladoga find their way to the Gulf of Finland. As our little boat — which had once done service as a canal boat in England — entered the river, I was charmed by the beautiful spectacle of Peter's City, now Petrograd. On the right, past the massive Nicholas Bridge, named in honour of St Nicholas, one of Russia's patron saints, stood the beautiful Cathedral of St Isaac, with its five cupolas of gilded copper shining in the morning sky like balls of molten gold against a background of azure. On the left, fronting the granite quays, were a number of splendid buildings, beginning with the palace of the Grand Duke Paul and ending with that classic structure, the Holy Synod, for many years the scene of Pobjedonodzeff's fanatical activity. On the opposite side of the river was the Vasilii Ostoff (Basil Island), with its miles of shipping and its stately front of offices and palatial buildings, many of which were inhabited by the merchant princes of the capital. Past the Nicholas Bridge was that stately block, the Academy of Arts, which owed its origin to Catherine the Great.

After a stormy passage in our little canal boat, now bravely doing service as a sea-going vessel, I was delighted to arrive at my destination in safety, and still more so to watch the scene before me — the great and wondrous creation of Peter awaking to life and activity, and the scene of my future joys, sorrows and labours for a quarter of a century. Suddenly I was awakened from my day-dreams by a gruff, hearty voice asking for my passport. "Passport!" I exclaimed in astonishment. "What do I want with a passport? Surely such a thing was never heard of since the days of the great Napoleon and the Continental system!" for even at that early age I was a "demon for history", as my literary friends called me. The captain was thunderstruck at my ignorance and my reply; I had but the haziest conception of Russia. "Napoleon be hanged", he replied. "I know nothing about the Continental system, but I know this, that imless you can produce a passport at once you will be arrested and the ship will be fined." As he spoke he pointed to a boat with two gendarme officers on board and also several dosmoschiks (searchers) rowing swiftly towards us. There was not a moment to lose, and the captain, evidently a man of resource, immediately rigged me out in a suit of oilskins and entered my name on the manifest as "cabin-boy." I was then told to go and range myself in line with others on the after-deck while the gendarmes keenly inspected each one of us and compared us with the names on the manifest. When it came to my turn they looked very suspiciously at the pale, girlish face and white hands of the little cabin-boy, whom they evidently suspected of sailing under false colours. After exchanging a few words with the captain and signing various documents in the cabin, the gendarmes and customs officers withdrew, leaving a wretched dosmoschik on board to watch the vessel. I could not help but think that he had been left behind to watch the author of this work, and therefore I confided my suspicions to that dear old sea-dog, the captain, who again came to my rescue. He invited the eager, brown-eyed dosmoschik into the cabin to have a drink of Swedish punch, a brew which has a peculiar power of robbing a man of the use of his legs before he is aware of it. After the unsuspecting searcher had taken three glasses of this golden liquid we were joined by the mate, who invited our amiable guest to partake of kümmel and other liqueurs. Presently both the captain and mate were called on deck to their duties, whilst I, the pale, innocent-looking cabin-boy, was left to do the honours as host. I listened while the dosmoschik's broken English grew more and more incoherent, until finally he dozed peacefully in the corner of the cabin, oblivious to the ship, the foreigners, the pale-faced youth and everything around him.

In this condition I left the man, probably dreaming of the lonely steppes and villages of Little Russia (for he was evidently a South Russian, judging from his appearance). The captain in the meantime had not been idle. Without losing any time he got out the long- boat, and after placing my box under the seat, beneath the folds of a large flag, ordered his men to row up the river and land me. This order was carried out, and in twenty minutes or so I found myself somewhere near the Baltic works, far away from the prying eyes of the customs officers. The mate, who accompanied us, chartered a droshky for me to the Cronstadt pier on the Vasilii Ostroff . Here I took a ticket by the Cronstadt steamer — an old English river boat dating from the days of Queen Victoria — and in one and a half hours I arrived in Cronstadt and was safe with my friends, who had long expected me. But I was not to be at rest for long, for as soon as my friends knew that I had no passport their anxiety on my account deprived me of all the pleasure I was experiencing in my new surroundings. It would never have done to tell the authorities how I had smuggled myself into "Holy Russia", so, after keeping me indoors nearly a fortnight, they decided to take the risk of getting a passport from a friend in England. This was duly signed, and in this irregular way, at sixteen years of age, I entered Russia — the country where I was to have so many interesting experiences and adventures during my twenty-seven years' sojourn.

As for the erring dosmoschik, I frequently used to meet him in the large square near the Customs House, but on seeing me he would drop his beady, brown eyes, for, like myself, he was suffering from the pangs of a guilty conscience — or perhaps from the effects of that never-to-be-forgotten spree on the little Viking, when he was so gloriously fuddled on punch, kümmel, vodka and port wine — an experience not easily forgotten in his othenvise dull, mieventful existence. These poor men have to endure a laborious life on a paltry wage, which hardly serves to keep body and soul together. All this happened nearly forty years ago, in those unregenerate days when the almighty rouble ruled Russia and vodka-drinking had not been abolished by an Imperial ukase.

As for the old captain who saved me from the dilemma, he has long since gone to his viking forbears, whilst his little boat lies at the bottom of the Gulf of Finland, beneath sixty fathoms of cold, blue water. About a couple of voyages after my arrival the Viking fomidered, with all on board except the captain. A terrible sea suddenly struck her, breaking open her hatches and putting out her fires. Being laden with Swedish iron and copper, she sank like a stone, with all hands on board, including the kind old stewardess who "mothered" me.

Before proceeding further with my narrative I must not forget to say that I was unusually lucky in not getting into serious trouble for not having a passport. Not every one is so fortunate, as the following incident will show. Shortly after my arrival an invalid clergyman, who had come out to Cronstadt for the good of his health, narrowly escaped imprisonment, for the gendarmes in Petrograd, hearing that he was on board an English steamer without that most necessary document, the passport, boarded the boat and arrested him. He was not even given time to go down to the cabin and get an overcoat, but was hurried into a boat and taken to the capital, with dire visions of the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul as his only companions. Had this unfortunate curate known more about Russia he would have escaped arrest, but his very ignorance and innocence were his undoing, for on being asked by the gendarmes what he was, he replied: "A student." "Skoobent“, ejaculated the gendarmes; "then away with him to the police station." In those days to be a student was synonymous with being a revolutionary. Almost every student was openly or secretly an antagonist to the Government. After the "conspirator" had been landed at the police station the English Vice-Consul was sent for, and it then transpired that the pale young gentleman in the black coat and white collar was "a student of theology"! — to the great disgust of his captors, who imagined that they had caught a dangerous person hiding on the steamboat prior to making his escape to the shores of perfidious Albion.*) Directly the mistake was cleared up the mihappy curate was liberated, with apologies. I have known many similar incidents — all arising from the negligence of Englishmen in not taking the few necessary precautions, either of procuring a passport or of having it properly vised before their departure for Russia.

*) It was a common practice in those days for fugitive students and other "politicals" to escape in English and German steamers from Russia. The good-natured captains, who sympathised with the revolutionists, would frequently hide them among the cargo, at considerable risk to themselves, for this was a serious offence in the eyes of the authorities.

On reaching the Gutaieffsky docks, which are a considerable distance from the capital, a traveller is obliged to make the acquaintance of that curious class of cabbies known in Russia as izvoschiks. Although they are attired in long, oriental-looking gowns reaching to their feet, and are crowned with a hat resembling that of a beef-eater, one must not think that these primitive-looking Jehus are half as simple as they appear to be; for inside the garb of childlike simplicity and innocence there often lurks a cunning and a ready wit which are really astonishing to anyone who does not understand the Russian moujik, from which class the Russian cabmen are generally recruited. As a rule, it is wise to offer only half the fare demanded, and even then to bargain until a figure is arrived at which is not too exorbitant. In fact, if the man is given what he originally asked, he will be sorry that he did not ask twice as much from the unsuspecting foreigner, while at the same time he will be disappointed at being deprived of the pleasure of bargaining, which to him is the salt of life. Should you by any chance get the better of him, he will usually show his displeasure by driving through the streets at a snail's pace, leaving you to fume with anger at his obstinacy, with the alternative of offering an extra tip if he will hurry. Usually when my Jehu treated me in this way, I would quietly get out of his droshky and jump into another one, much to the astonishment of the deeply offended driver of the first vehicle, whose face, when he finally turned round, was a study. He had lost both his "fare" and the money! These men, however, if treated well, are generally very kind-hearted and willing to drive like a whirlwind if you should be in a hurry to catch a train. On these occasions I have sometimes had to catch hold of the reins and pull the horse in, especially if there happened to be another cab going in the same direction, for a mad race would begin, when I was in constant danger of being thrown out on the hard cobbles and breaking my neck. Should remonstrance be in vain, the driver, if he has been promised a good fare, will turn round with a grin and console his passenger with one of numerous proverbs: "Life is a copeck", *) "You can only die once, so what does it matter", or something in a similar vein.

*) 1 copeck = 1 farthing ; 100 copecks = 1 rouble, about 2S;

A kindly smile and a gentle manner will go a long way with these hardy, struggling, long-haired fellows. As an example of this I can quote the case of an English governess who always managed to drive at half the proper fare, because she called her driver golubbchik (little pigeon) and smiled on him very sweetly. You might smile like the wonderful cat of Alice in Wonderland without much effect on an English or German driver's charges; but in Russia these little matters go a long way. The simple moujik looks with wonder and astonishment on all foreigners, and in his heart thinks them all beneath him, for are they not heretics without the true faith, which is going to ensure him a happy place hereafter, even if at present he does not have his full share of the plums?

On arriving at a hotel a traveller must hand his passport to the proprietor or hall porter. It must be "written in", as it is termed in Russia, otherwise a person may find that he will have to pay a heavy fine, or perhaps even be detained. I have known people to be delayed weeks, simply because they did not attend to small matters of this kind. The passport system may have its disadvantages, but it also confers some benefits on the country where it is in force; it gives a certain hold over the criminal population and anyone who is dangerous to the Government. If people do not pay their trades-people, the police are informed, and the debtor may not leave the country until the debt has been discharged. If a wife leaves her husband she can easily be brought back, for she is not allowed to have a separate passport such as an unmarried woman possesses. If need be, she can be brought back etapom (on foot) and sent under convoy from one police station to another until she reaches the place from whence she started. Russian husbands have many privileges which are denied to married men in England, where wives probably have more liberties than the married women of any other Euro- pean country. Providing a passport is in order, there is no reason why an Englishman, visiting Russia, should be caused any annoyance or inconvenience. As long as he keeps to his own business and avoids politics as one would the plague, a traveller is perfectly safe. If engaged in business or trade, the local police-man expects a certain sum for looking after the trades-man's property. These men are paid a starvation wage by the Government and look to "tips" to help them to exist. The system is an old Tartar survival and has much to do with the corruption in official circles. The Government evidently believe in paying their officials the smallest possible salaries, believing that those who are sensible will make up the deficiency by taking from the Tsar's subjects podarke and nachais (presents and tea money). So long as this practice does not go too far, it is winked at by the authorities, but if an official is found to be systematically taking advantage of his position, some day he may find himself confronted by a revisor (inspector), and a few days afterwards he will be en route for Siberia at the Crown's expense.

With regard to the practice of bribing officials, in the days of Catherine this pernicious system flourished in all its glory. It is related that on one occasion, when an official complained to the Empress that his salary was too small, "the mother of her people", as she delighted to call herself, and which she was in more senses than one, replied: "The man's a fool ; he has been placed near the trough, but the ass won't feed himself." Peter the Great, however, who had imbibed some Western ideas on this subject, used to whack his ministers without mercy when convicted of corruption, unless by way of a change he took it into his head to hang, draw and quarter them. Nicholas I.,*) who was much misrepresented by contemporary historians, was extremely particular about his servants taking bribes, and on one occasion, when he discovered that his palace architect had been guilty of corruption and deceit, struck him with his fist and killed him on the spot. But as Russians come more into contact with the people of the West, and as they receive better remuneration for their services, the practice of bribing and taking bribes will gradually die out, especially in those portions of the Empire which are in close contact with the seat of government.

*) John Maxwell, in his excellent and trustworthy work entitled The Tsar, his Court and People, published by Bentley in 1854, gives the following just estimate of the character of Nicholas I. : — "By nature ardent and generous; possessing most noble and most generous qualities; gifted with very considerable mental ability and great personal beauty and bodily strength; his errors are to be regarded as those of position, rather than those of inclination. The cruel death of his father, the weakness and misfortunes of his brothers, and the bloody events attending his own succession to the throne, seem to have determined him to pursue a course of policy more in keeping with a soldier's idea of order and security, than one distinguished for prudence, wisdom and moderation.“

I. ARRIVAL IN PETROGRAD AND THE NECESSITY FOR PASSPORTS

II. CRONSTADT, THE KEY OF PETROGRAD, AND SOME MEMORIES

III. A ZEALOT OF CRONSTADT

IV. SOME CRONSTADT CHARACTERS

V. THE FOUNDING OF PETROGRAD

VI. THE YOUTH AND GROWTH OF PETROGRAD, WITH SOME HISTORICAL NOTES

VII. THE RIVER NEVA AND THE GREAT FLOODS

VIII. THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1777; THE DEATH OF PRINCESS TAUAKANOFFVA

IX. PETROGRAD DURING THE UEIGN OF ITS FOUNDER; AND AN ACCOUNT OF PETER'S COURT AS SEEN BY PRINCESS WILHELMINA OF PRUSSIA

X. STATUES AND MONUMENTS, HISTORICAL MEMORIES AND SOME SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE CAPITAL

XI. A TRIP UP THE NEVA

XII. THE FORTRESS OF PETER AND PAUL

XIII. THE MODERN CITY AND THE PEOPLE

XIV. THE POLICE OF PETROGRAD

XV. OFFICIALDOM IN RUSSIA

XVI. THE MOUJIKS AND WORKING CLASSES

XVII. THE TSAR, HIS HOUSEHOLD AND HIS LABOURS

XVIII. HOTELS AND RESTAURANTS

XIX. THEATRES, CONCERTS AND PLEASURE GARDENS

XX. CONCERNING THE BALLET

XXI. THE HERMITAGE AND ITS MEMORIES CATHERINE'S FAVOURITE RETREAT

XXII. THE ANITCHKOFF PALACE AND A NARROW ESCAPE

XXIII. THE TAURIDA PALACE AND THE WINTER PALACE

XXIV. THE ALEXANDER NEVSKY MONASTERY

XXV. THE KAZAN CATHEDRAL, THE RIOTS, AND ST ISAAC'S CATHEDRAL

XXVI. TWO TSARS : PAUL, THE "MAD TSAR"; NICHOLAS I., HIS CHARACTER AND AMBITION

XXVII. SIR ROBERT MORIER AND THE BRITISH EMBASSY

XXVIII. COUNT SERGIUS DE WITTE

XXIX. THE RUSSIAN PRESS

XXX. FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS AND THE CENSORS

XXXI. THE BRITISH COLONY — ITS HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

XXXII. KRASNOE SELO AND THE MILITARY MANEUVRES

XXXIII. ALEXANDER III., HIS "MUSEUM," AND THE LATE GRAND DUKE CONSTANTINE

XXXIV. THE ENVIRONS OF THE CITY

THE GRAND DUKE MICHAEL, THE TSAR'S BROTHER, AT THE FRONT

A NOTE ON THE GROWTH OF THE RUSSIAN EMIMUE SINCE THE DAYS OF PETER THE GREAT

SOME AUTHORITIES REFERRED TO FOR THE PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK

INDEX

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

01. The Church of the Resurrection of Christ

02. Two very Important Personages

03. The Steamer Yermak breaking its way through the Ice

04. Father John of Cronstadt

05. The Cousins: the Tsar and King George

06. Building Ships for Russia's Commercial Marine in the Days of Peter the Great

07. Petrograd in the Days of Catherine II.

08. The deep and rapid Neva, with View of the Nicholai Bridge

09. A Crowd on the Nevsky Prospect: "Praznek"

10. The Catherine Canal

11. The Last Days of the beautiful Princess Tarakanoffva in the Fortress

12. A Masquerade in the Days of Peter the Great (1722)

13. The old Winter Palace

14. The Admiralty with its Gilded Spire

15. The Fortress Church of SS. Peter and Paul

16. Russian Railway Guard

17. Typical Russian Coachman

18. A typical Russian Moujik in the Rough State

19. Russian Peasant begging for Alms for the Village Church

20. The Facade of the Imperial Hermitage

21. „Babooshka" Ekaterina II.

22. The Mechailoff Palace, now converted into the Museum of Alexander III.

23. The Anitchkoff Palace on the Nevsky

24. The Kazan Cathedral

25. The Gosteny Dvor (Guest Bazaar) on the Nevsky

26. The Cathedral of St Isaac of Dalmatia

27. The old Mechailoff Palace

28. Russian Standard Bearers of the Guards

29. The Tsar Alexander III.— called the "Peace-lover"

30. The Palace and wonderful Fountains of Peterhoff

I. THE ARRIVAL IN PETROGRAD AND THE NECESSITY FOR PASSPORTS

It was a lovely morning in May when our diminutive steamer the Viking first entered the swift stream of the Neva, by which river the confined and pentup waters of Lake Ladoga find their way to the Gulf of Finland. As our little boat — which had once done service as a canal boat in England — entered the river, I was charmed by the beautiful spectacle of Peter's City, now Petrograd. On the right, past the massive Nicholas Bridge, named in honour of St Nicholas, one of Russia's patron saints, stood the beautiful Cathedral of St Isaac, with its five cupolas of gilded copper shining in the morning sky like balls of molten gold against a background of azure. On the left, fronting the granite quays, were a number of splendid buildings, beginning with the palace of the Grand Duke Paul and ending with that classic structure, the Holy Synod, for many years the scene of Pobjedonodzeff's fanatical activity. On the opposite side of the river was the Vasilii Ostoff (Basil Island), with its miles of shipping and its stately front of offices and palatial buildings, many of which were inhabited by the merchant princes of the capital. Past the Nicholas Bridge was that stately block, the Academy of Arts, which owed its origin to Catherine the Great.

After a stormy passage in our little canal boat, now bravely doing service as a sea-going vessel, I was delighted to arrive at my destination in safety, and still more so to watch the scene before me — the great and wondrous creation of Peter awaking to life and activity, and the scene of my future joys, sorrows and labours for a quarter of a century. Suddenly I was awakened from my day-dreams by a gruff, hearty voice asking for my passport. "Passport!" I exclaimed in astonishment. "What do I want with a passport? Surely such a thing was never heard of since the days of the great Napoleon and the Continental system!" for even at that early age I was a "demon for history", as my literary friends called me. The captain was thunderstruck at my ignorance and my reply; I had but the haziest conception of Russia. "Napoleon be hanged", he replied. "I know nothing about the Continental system, but I know this, that imless you can produce a passport at once you will be arrested and the ship will be fined." As he spoke he pointed to a boat with two gendarme officers on board and also several dosmoschiks (searchers) rowing swiftly towards us. There was not a moment to lose, and the captain, evidently a man of resource, immediately rigged me out in a suit of oilskins and entered my name on the manifest as "cabin-boy." I was then told to go and range myself in line with others on the after-deck while the gendarmes keenly inspected each one of us and compared us with the names on the manifest. When it came to my turn they looked very suspiciously at the pale, girlish face and white hands of the little cabin-boy, whom they evidently suspected of sailing under false colours. After exchanging a few words with the captain and signing various documents in the cabin, the gendarmes and customs officers withdrew, leaving a wretched dosmoschik on board to watch the vessel. I could not help but think that he had been left behind to watch the author of this work, and therefore I confided my suspicions to that dear old sea-dog, the captain, who again came to my rescue. He invited the eager, brown-eyed dosmoschik into the cabin to have a drink of Swedish punch, a brew which has a peculiar power of robbing a man of the use of his legs before he is aware of it. After the unsuspecting searcher had taken three glasses of this golden liquid we were joined by the mate, who invited our amiable guest to partake of kümmel and other liqueurs. Presently both the captain and mate were called on deck to their duties, whilst I, the pale, innocent-looking cabin-boy, was left to do the honours as host. I listened while the dosmoschik's broken English grew more and more incoherent, until finally he dozed peacefully in the corner of the cabin, oblivious to the ship, the foreigners, the pale-faced youth and everything around him.

In this condition I left the man, probably dreaming of the lonely steppes and villages of Little Russia (for he was evidently a South Russian, judging from his appearance). The captain in the meantime had not been idle. Without losing any time he got out the long- boat, and after placing my box under the seat, beneath the folds of a large flag, ordered his men to row up the river and land me. This order was carried out, and in twenty minutes or so I found myself somewhere near the Baltic works, far away from the prying eyes of the customs officers. The mate, who accompanied us, chartered a droshky for me to the Cronstadt pier on the Vasilii Ostroff . Here I took a ticket by the Cronstadt steamer — an old English river boat dating from the days of Queen Victoria — and in one and a half hours I arrived in Cronstadt and was safe with my friends, who had long expected me. But I was not to be at rest for long, for as soon as my friends knew that I had no passport their anxiety on my account deprived me of all the pleasure I was experiencing in my new surroundings. It would never have done to tell the authorities how I had smuggled myself into "Holy Russia", so, after keeping me indoors nearly a fortnight, they decided to take the risk of getting a passport from a friend in England. This was duly signed, and in this irregular way, at sixteen years of age, I entered Russia — the country where I was to have so many interesting experiences and adventures during my twenty-seven years' sojourn.

As for the erring dosmoschik, I frequently used to meet him in the large square near the Customs House, but on seeing me he would drop his beady, brown eyes, for, like myself, he was suffering from the pangs of a guilty conscience — or perhaps from the effects of that never-to-be-forgotten spree on the little Viking, when he was so gloriously fuddled on punch, kümmel, vodka and port wine — an experience not easily forgotten in his othenvise dull, mieventful existence. These poor men have to endure a laborious life on a paltry wage, which hardly serves to keep body and soul together. All this happened nearly forty years ago, in those unregenerate days when the almighty rouble ruled Russia and vodka-drinking had not been abolished by an Imperial ukase.

As for the old captain who saved me from the dilemma, he has long since gone to his viking forbears, whilst his little boat lies at the bottom of the Gulf of Finland, beneath sixty fathoms of cold, blue water. About a couple of voyages after my arrival the Viking fomidered, with all on board except the captain. A terrible sea suddenly struck her, breaking open her hatches and putting out her fires. Being laden with Swedish iron and copper, she sank like a stone, with all hands on board, including the kind old stewardess who "mothered" me.

Before proceeding further with my narrative I must not forget to say that I was unusually lucky in not getting into serious trouble for not having a passport. Not every one is so fortunate, as the following incident will show. Shortly after my arrival an invalid clergyman, who had come out to Cronstadt for the good of his health, narrowly escaped imprisonment, for the gendarmes in Petrograd, hearing that he was on board an English steamer without that most necessary document, the passport, boarded the boat and arrested him. He was not even given time to go down to the cabin and get an overcoat, but was hurried into a boat and taken to the capital, with dire visions of the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul as his only companions. Had this unfortunate curate known more about Russia he would have escaped arrest, but his very ignorance and innocence were his undoing, for on being asked by the gendarmes what he was, he replied: "A student." "Skoobent“, ejaculated the gendarmes; "then away with him to the police station." In those days to be a student was synonymous with being a revolutionary. Almost every student was openly or secretly an antagonist to the Government. After the "conspirator" had been landed at the police station the English Vice-Consul was sent for, and it then transpired that the pale young gentleman in the black coat and white collar was "a student of theology"! — to the great disgust of his captors, who imagined that they had caught a dangerous person hiding on the steamboat prior to making his escape to the shores of perfidious Albion.*) Directly the mistake was cleared up the mihappy curate was liberated, with apologies. I have known many similar incidents — all arising from the negligence of Englishmen in not taking the few necessary precautions, either of procuring a passport or of having it properly vised before their departure for Russia.

*) It was a common practice in those days for fugitive students and other "politicals" to escape in English and German steamers from Russia. The good-natured captains, who sympathised with the revolutionists, would frequently hide them among the cargo, at considerable risk to themselves, for this was a serious offence in the eyes of the authorities.

On reaching the Gutaieffsky docks, which are a considerable distance from the capital, a traveller is obliged to make the acquaintance of that curious class of cabbies known in Russia as izvoschiks. Although they are attired in long, oriental-looking gowns reaching to their feet, and are crowned with a hat resembling that of a beef-eater, one must not think that these primitive-looking Jehus are half as simple as they appear to be; for inside the garb of childlike simplicity and innocence there often lurks a cunning and a ready wit which are really astonishing to anyone who does not understand the Russian moujik, from which class the Russian cabmen are generally recruited. As a rule, it is wise to offer only half the fare demanded, and even then to bargain until a figure is arrived at which is not too exorbitant. In fact, if the man is given what he originally asked, he will be sorry that he did not ask twice as much from the unsuspecting foreigner, while at the same time he will be disappointed at being deprived of the pleasure of bargaining, which to him is the salt of life. Should you by any chance get the better of him, he will usually show his displeasure by driving through the streets at a snail's pace, leaving you to fume with anger at his obstinacy, with the alternative of offering an extra tip if he will hurry. Usually when my Jehu treated me in this way, I would quietly get out of his droshky and jump into another one, much to the astonishment of the deeply offended driver of the first vehicle, whose face, when he finally turned round, was a study. He had lost both his "fare" and the money! These men, however, if treated well, are generally very kind-hearted and willing to drive like a whirlwind if you should be in a hurry to catch a train. On these occasions I have sometimes had to catch hold of the reins and pull the horse in, especially if there happened to be another cab going in the same direction, for a mad race would begin, when I was in constant danger of being thrown out on the hard cobbles and breaking my neck. Should remonstrance be in vain, the driver, if he has been promised a good fare, will turn round with a grin and console his passenger with one of numerous proverbs: "Life is a copeck", *) "You can only die once, so what does it matter", or something in a similar vein.

*) 1 copeck = 1 farthing ; 100 copecks = 1 rouble, about 2S;

A kindly smile and a gentle manner will go a long way with these hardy, struggling, long-haired fellows. As an example of this I can quote the case of an English governess who always managed to drive at half the proper fare, because she called her driver golubbchik (little pigeon) and smiled on him very sweetly. You might smile like the wonderful cat of Alice in Wonderland without much effect on an English or German driver's charges; but in Russia these little matters go a long way. The simple moujik looks with wonder and astonishment on all foreigners, and in his heart thinks them all beneath him, for are they not heretics without the true faith, which is going to ensure him a happy place hereafter, even if at present he does not have his full share of the plums?

On arriving at a hotel a traveller must hand his passport to the proprietor or hall porter. It must be "written in", as it is termed in Russia, otherwise a person may find that he will have to pay a heavy fine, or perhaps even be detained. I have known people to be delayed weeks, simply because they did not attend to small matters of this kind. The passport system may have its disadvantages, but it also confers some benefits on the country where it is in force; it gives a certain hold over the criminal population and anyone who is dangerous to the Government. If people do not pay their trades-people, the police are informed, and the debtor may not leave the country until the debt has been discharged. If a wife leaves her husband she can easily be brought back, for she is not allowed to have a separate passport such as an unmarried woman possesses. If need be, she can be brought back etapom (on foot) and sent under convoy from one police station to another until she reaches the place from whence she started. Russian husbands have many privileges which are denied to married men in England, where wives probably have more liberties than the married women of any other Euro- pean country. Providing a passport is in order, there is no reason why an Englishman, visiting Russia, should be caused any annoyance or inconvenience. As long as he keeps to his own business and avoids politics as one would the plague, a traveller is perfectly safe. If engaged in business or trade, the local police-man expects a certain sum for looking after the trades-man's property. These men are paid a starvation wage by the Government and look to "tips" to help them to exist. The system is an old Tartar survival and has much to do with the corruption in official circles. The Government evidently believe in paying their officials the smallest possible salaries, believing that those who are sensible will make up the deficiency by taking from the Tsar's subjects podarke and nachais (presents and tea money). So long as this practice does not go too far, it is winked at by the authorities, but if an official is found to be systematically taking advantage of his position, some day he may find himself confronted by a revisor (inspector), and a few days afterwards he will be en route for Siberia at the Crown's expense.

With regard to the practice of bribing officials, in the days of Catherine this pernicious system flourished in all its glory. It is related that on one occasion, when an official complained to the Empress that his salary was too small, "the mother of her people", as she delighted to call herself, and which she was in more senses than one, replied: "The man's a fool ; he has been placed near the trough, but the ass won't feed himself." Peter the Great, however, who had imbibed some Western ideas on this subject, used to whack his ministers without mercy when convicted of corruption, unless by way of a change he took it into his head to hang, draw and quarter them. Nicholas I.,*) who was much misrepresented by contemporary historians, was extremely particular about his servants taking bribes, and on one occasion, when he discovered that his palace architect had been guilty of corruption and deceit, struck him with his fist and killed him on the spot. But as Russians come more into contact with the people of the West, and as they receive better remuneration for their services, the practice of bribing and taking bribes will gradually die out, especially in those portions of the Empire which are in close contact with the seat of government.

*) John Maxwell, in his excellent and trustworthy work entitled The Tsar, his Court and People, published by Bentley in 1854, gives the following just estimate of the character of Nicholas I. : — "By nature ardent and generous; possessing most noble and most generous qualities; gifted with very considerable mental ability and great personal beauty and bodily strength; his errors are to be regarded as those of position, rather than those of inclination. The cruel death of his father, the weakness and misfortunes of his brothers, and the bloody events attending his own succession to the throne, seem to have determined him to pursue a course of policy more in keeping with a soldier's idea of order and security, than one distinguished for prudence, wisdom and moderation.“