BEOWULF

A Poem by Dr. Samuel Harden Church.

Autor: Church, Samuel Harden Dr. (1858-1943), Erscheinungsjahr: 1901

Themenbereiche

Author of “Oliver Cromwell: A History”

“John Marmaduke: A Romance” Etc.

“John Marmaduke: A Romance” Etc.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- The Sea Waif.

- The Flaming Sword.

- Grendel.

- The Swamp-Hag.

- The Fire-Dragon

- A Warwick Nightingale

- Lines on Cromwell’s Three Hundredth

- Birthday

Preface.

For a long time I had it in mind to make a translation of the old Anglo-Saxon Saga, Beowulf, in poetical form, and pursued a preliminary study of the manuscript, charred from the Cottonian fire, in the British Museum. That work, the oldest monument of the Anglo-Saxon language, is a very noble heritage from a great, though unknown, authorship, full of rugged strength; and it should be read by every student of literature. But when I began to cast the materials over, I found them lacking in qualities of human interest that are necessary to modern poetical narrative.

The old Beowulf is a minstrel’s song of hero deeds, in which a period of four generations is covered. The tale opens with Sceaf the Scylding, who comes out of the sea, is made King, dies, and is sent back into the sea in the opening lines. There is his son, who is called Beowulf, and Beowulf’s son is Hrothgar. While this Hrothgar is on the throne, there comes another Beowulf, a Gothic warrior, who fights with Grendel and with the Water-Hag, and then goes back to his own country, where he is made King, and, after reigning for fifty years, is killed in extreme old age in a fight with a Dragon. The old poem has thus no unity of time or place; neither has it any portraiture of womanhood; and there is no suggestion of a love story. The action takes place in Denmark and in Sweden; yet the claim has been made that the scenery described is in England. It seems clear that the Angles and Saxons, who were neighbors of the Danes on the Continent, brought the story over to England, and that it was made to assume literary form before the Danes forced themselves into England as conquerors.

Besides, there were already literal translations of the Saga by Kemble, Thorp, Harrison and Sharp, Garnett, Earle, and William Morris; making another direct rendering a supererogant labor.

While adhering to the purpose to write a poem on the adventures of Beowulf, these circumstances impelled me to abandon the intention of a general agreement with the ancient version. I have therefore composed an original narrative, in which the leading characters and some of the incidents of the early work have been freely used, but as materials only. I have transferred to my hero, Beowulf, the picturesque history of Sceaf; have changed the relationship of characters and incidents; have invented the illumination of Beowulf’s soul and his banishment; and have introduced the love motive between Beowulf and Freaware that runs through the poem to the end. Indeed, the structure, language, style, description, elaboration, interpretation, and development of the story are new. I have arbitrarily laid the scene in England, under purely idealized conditions; and have initiated nearly all that the poem contains of womanhood, of love, of religion and state policy, and of domestic life and manners. It is clear, there fore, that my work must not be judged either as a translation, version, or paraphrase of the old Beowulf.

Were the fabled monsters of olden times wholly creatures of the imagination? I think not. Paleontology has already restored their bones to us — or bones very like theirs.*) It requires no great strain of fancy to think of such creatures in the swamps, and of the King offering guerdon and his daughter’s hand to him who would slay them. But perhaps they are allegorical of human ills. What man is there to-day who has not met his Dragon? What nation still lives that has not overcome its Grendel?

*) In the Carnegie Museum at Pittsburg they have the fossil remains

of a beast, the Terrible Lizard, nearly one hundred feet long; and the British Museum has just sent an expedition to Patagonia to find a living Megatherium.

List of illustrations by Albert Grantley Reihnhardt.

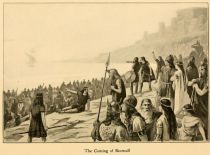

001. The Coming of Beowulf. Frontispiece

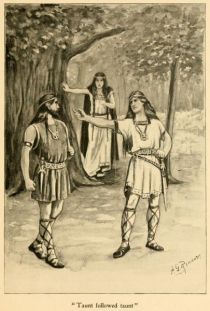

002. “Taunt followed taunt”. 24

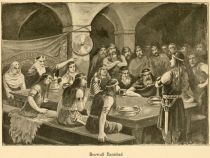

003. Beowulf Banished. 34

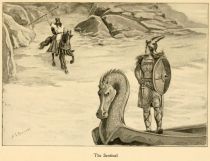

004. The Sentinel. 44

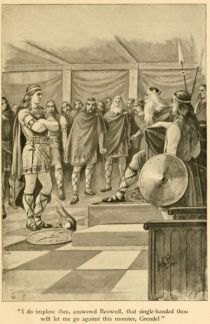

005. “I do implore thee”. 50

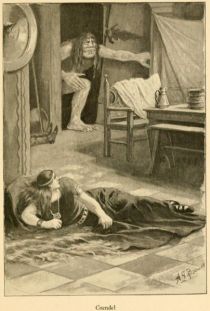

006. Grendel. 60

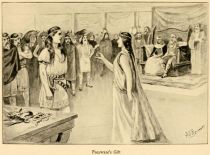

007. Freaware’s Gift. 66

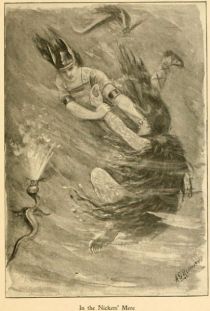

008. In the Nickers’ Mere. 74

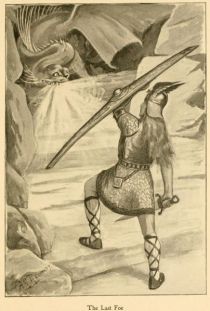

009. The Last Foe. 100

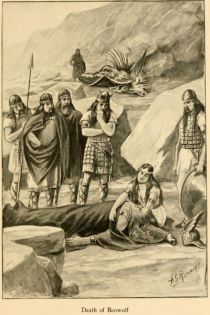

010. Death of Beowulf. 104

011. Tail-piece. 117

For a long time I had it in mind to make a translation of the old Anglo-Saxon Saga, Beowulf, in poetical form, and pursued a preliminary study of the manuscript, charred from the Cottonian fire, in the British Museum. That work, the oldest monument of the Anglo-Saxon language, is a very noble heritage from a great, though unknown, authorship, full of rugged strength; and it should be read by every student of literature. But when I began to cast the materials over, I found them lacking in qualities of human interest that are necessary to modern poetical narrative.

The old Beowulf is a minstrel’s song of hero deeds, in which a period of four generations is covered. The tale opens with Sceaf the Scylding, who comes out of the sea, is made King, dies, and is sent back into the sea in the opening lines. There is his son, who is called Beowulf, and Beowulf’s son is Hrothgar. While this Hrothgar is on the throne, there comes another Beowulf, a Gothic warrior, who fights with Grendel and with the Water-Hag, and then goes back to his own country, where he is made King, and, after reigning for fifty years, is killed in extreme old age in a fight with a Dragon. The old poem has thus no unity of time or place; neither has it any portraiture of womanhood; and there is no suggestion of a love story. The action takes place in Denmark and in Sweden; yet the claim has been made that the scenery described is in England. It seems clear that the Angles and Saxons, who were neighbors of the Danes on the Continent, brought the story over to England, and that it was made to assume literary form before the Danes forced themselves into England as conquerors.

Besides, there were already literal translations of the Saga by Kemble, Thorp, Harrison and Sharp, Garnett, Earle, and William Morris; making another direct rendering a supererogant labor.

While adhering to the purpose to write a poem on the adventures of Beowulf, these circumstances impelled me to abandon the intention of a general agreement with the ancient version. I have therefore composed an original narrative, in which the leading characters and some of the incidents of the early work have been freely used, but as materials only. I have transferred to my hero, Beowulf, the picturesque history of Sceaf; have changed the relationship of characters and incidents; have invented the illumination of Beowulf’s soul and his banishment; and have introduced the love motive between Beowulf and Freaware that runs through the poem to the end. Indeed, the structure, language, style, description, elaboration, interpretation, and development of the story are new. I have arbitrarily laid the scene in England, under purely idealized conditions; and have initiated nearly all that the poem contains of womanhood, of love, of religion and state policy, and of domestic life and manners. It is clear, there fore, that my work must not be judged either as a translation, version, or paraphrase of the old Beowulf.

Were the fabled monsters of olden times wholly creatures of the imagination? I think not. Paleontology has already restored their bones to us — or bones very like theirs.*) It requires no great strain of fancy to think of such creatures in the swamps, and of the King offering guerdon and his daughter’s hand to him who would slay them. But perhaps they are allegorical of human ills. What man is there to-day who has not met his Dragon? What nation still lives that has not overcome its Grendel?

*) In the Carnegie Museum at Pittsburg they have the fossil remains

of a beast, the Terrible Lizard, nearly one hundred feet long; and the British Museum has just sent an expedition to Patagonia to find a living Megatherium.

List of illustrations by Albert Grantley Reihnhardt.

001. The Coming of Beowulf. Frontispiece

002. “Taunt followed taunt”. 24

003. Beowulf Banished. 34

004. The Sentinel. 44

005. “I do implore thee”. 50

006. Grendel. 60

007. Freaware’s Gift. 66

008. In the Nickers’ Mere. 74

009. The Last Foe. 100

010. Death of Beowulf. 104

011. Tail-piece. 117